By Patricia Leach

This article was published in our Winter 2021 newsletter. Read more of the newsletter here.

In 1765, at the incorporation of our town as “Williams Town,” there was not a true meetinghouse, per se. Services featuring our newly settled minister, Yale graduate Whitman Welch, were held in the young settlement’s log schoolhouse. But soon, as early as 1766, the need for a dedicated meetinghouse was realized. Although it was not an expensive project—its cost was approximately $600 and many white oak trees, a primary building material, were available nearby—construction went slowly. By 1768, however, a tiny 40 x 30 ft meetinghouse was established on the Square (now known as Field Park).

As our revered Williamstown historian, Arthur Latham Perry, tells us: “Lumber was exceedingly abundant….the sills and corner-posts…the rafters and studs and braces, and certainly all the pins that in those days fastened the [white oak] timbers together….these were likely ‘sawed out at John Smedley’s mill, two miles north of the building site, along a fair road passing near what is now the Vermont line.’” While there were other local options, Smedley’s brother served on the first meetinghouse building committee and might be expected to have influenced the choice of a supplier. But what did this original little meetinghouse look like?

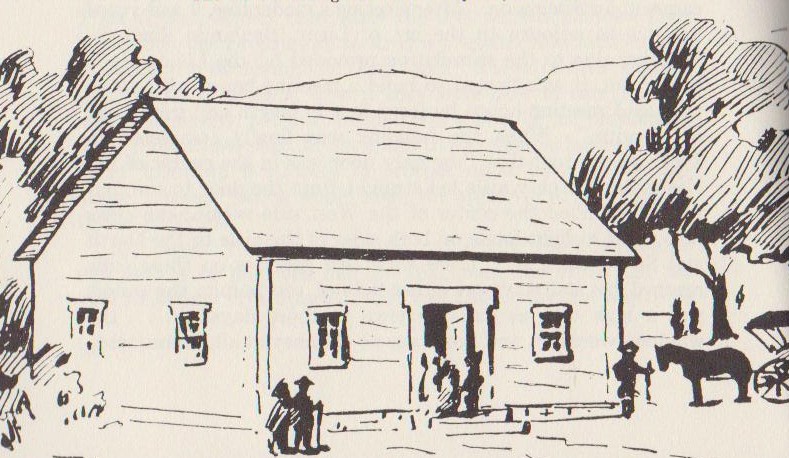

Perry tells us this: “The ridge pole ran north and south the longer way of the building, which was 40 feet. The roof was plain, without belfry, or tower, or other protuberance whatever. The only door was in the centre of the east side; the only aisle led straight from the door to the pulpit, which filled the center of the west side within; the pews rose up at a slight angle on both sides of the aisle to the north and south ends, which were thirty feet each; there were two galleries on these ends, reached by stairways on either side of the pulpit; the pulpit was a high one, as was universal in those days, and the preacher preached at right angles to the people; that is to say, the audience on the south side of the aisle below and above fronted [faced] exactly the audience on the north side below and above; it is no more than charity allows us moderns to infer, that the young people (perhaps the old ones too) watched each other more than they watched the minister (this author’s italics). The windows were few, and there was no chimney at all, consequently the room was relatively dark and cold; the site was high, in the middle of Main Street and at the junction of that with two cross streets, exposed to all winds in all weathers, but somewhat protected, after all, in the fact that there was no door or other opening on the west side or either end.”

The little building hosted meetings of the Proprietors as well as church services. From ca. 1795, it also accommodated town meetings (until 1828) along with “schools” in the summer until well into the 19th c. By that time the meetinghouse’s interior, which still possessed its pulpit, had degenerated into a “dark and dismal den” “peopled by spooks” according to one young scholar. And, in 1828, someone set it on fire and in no time, it lay in ashes. But even before its sorry end in the fire of 1828, it had lost its prominent position on the Square: in 1796, a new meetinghouse was proposed. And, to give this new building pride-of-place, the old meetinghouse was moved further west and pivoted around. By 1798, a new Second Meetinghouse, “more than twice the size” of its tiny predecessor, was hosting Williams College Commencement.

For more on our meetinghouses, join us for Patricia Leach’s lecture on May 29. Zoom links will be posted on our website and Facebook page.