“How Women Got the Vote is a Far More Complex Story than History Textbooks Reveal,” by Alicia Ault, Smithsonian Magazine Woman Suffrage is now taken for granted, however, in this online exhibit, with the help and generous contributions of research from The Northern Berkshire Suffrage Centennial Coalition, the WHM celebrates the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment. We will look at the Woman Suffrage movement, its progress in the region, key suffragists, and women who have made a difference since the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Massachusetts residents played a significant role in the Woman Suffrage movement, and author Barbara Berenson wrote an accessible and informative book, titled Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement. We encourage you to learn more about the book by clicking on the image below to go to the webpage for the book and you can click on the button below to hear an audio interview of the author.

Radio Interview with Barbara Berenson

Phoebe Jordan

Berkshire County’s second most famous suffragist is Phoebe Sarah Jordan (1864-1940) of New Ashford, MA, and yet few County residents know who she was, why she is noteworthy, or have seen a photo of her, even though there are people still alive today with childhood memories of her.

Her current claim to fame is that she was the first American woman to legally vote in a presidential election in November of 1920, after the ratification of the 19th Amendment. But that is not the headline on her Berkshire Eagle obituary.

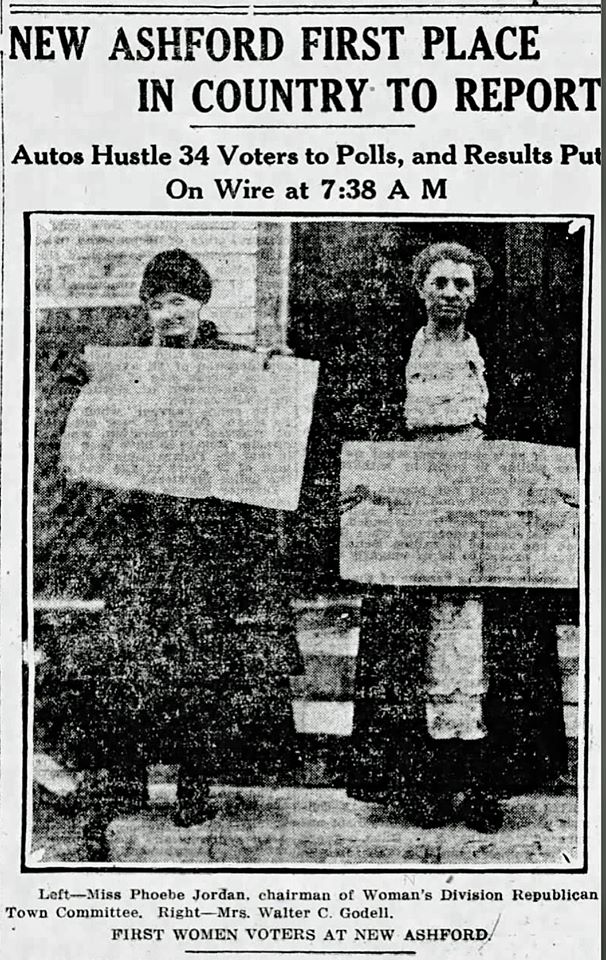

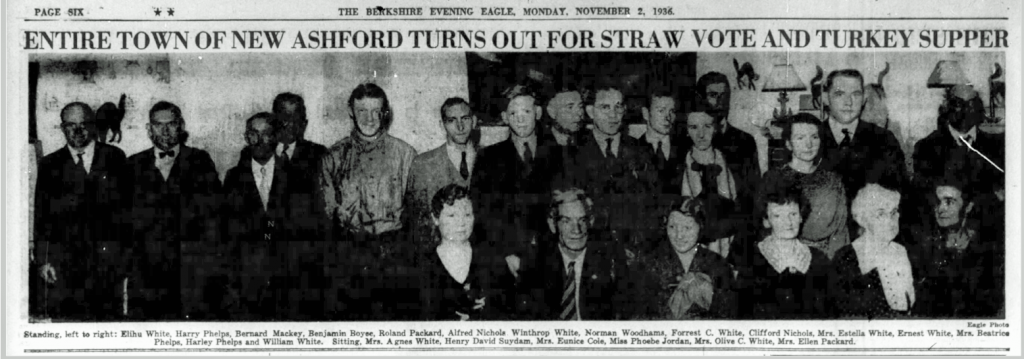

For five national elections, from 1916-1932, New Ashford was the first town in the nation to cast its ballots (Dixville Notch, NH, usurped that honor at the 1936 election) thanks to a publicity scheme cooked up by Dennis J. Haylon, managing editor of the Berkshire Eagle, and Carey S. Hayward, city editor of the Pittsfield Journal, to open the polls in what was then the Commonwealth’s smallest town, at 6 am. With the cooperation of the three dozen or so voters, it was possible for New Ashford to be the first community to report election returns.

Boston Globe, November 3, 1920

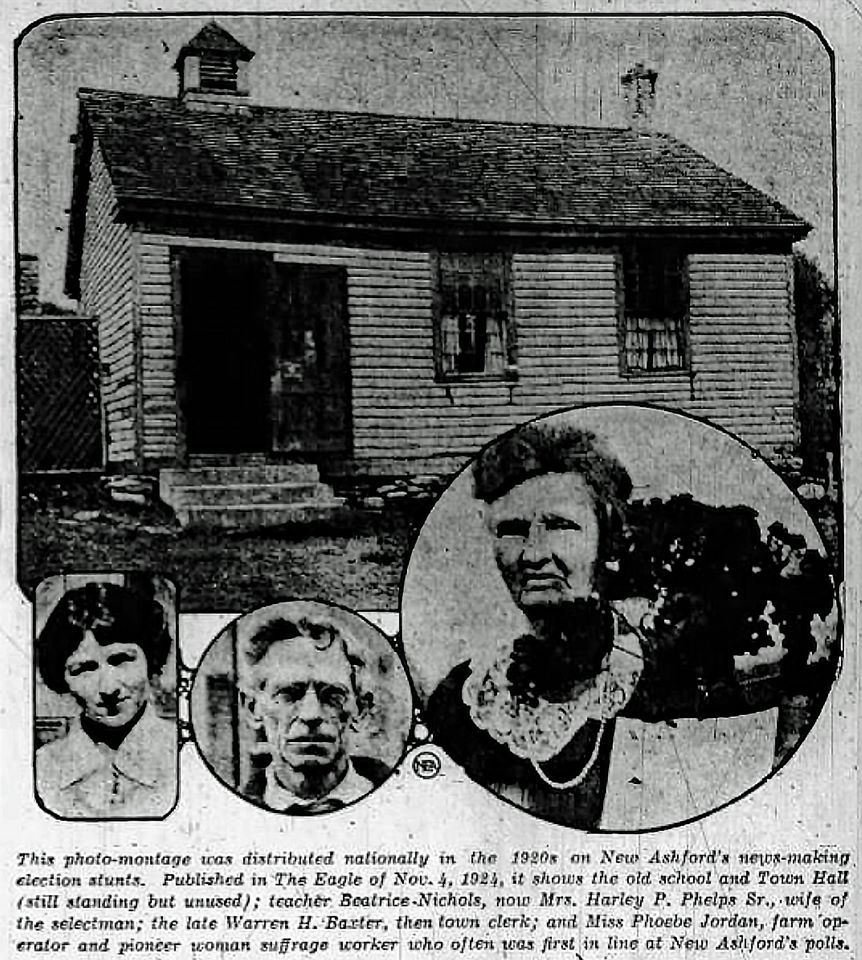

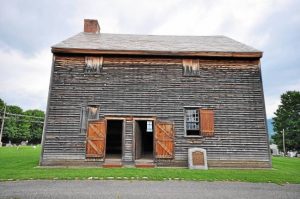

Elections were held in what was then the schoolhouse on Mallery Road – since restored and known as the 1792 Schoolhouse, and since automobiles – not to mention paved roads – were still a novelty in 1916, many voters, including Jordan, arrived on foot.

Photo montage of New Ashford 1792 schoolhouse, Beatrice Nichols Phelps, Warren H. Baxter and Phoebe Jordan in a Berkshire Eagle retrospective article August, 1955.

1792 Schoolhouse, New Ashford

1792 Schoolhouse, New Ashford

iBerkshires photo of the alumni of the 1792 Schoolhouse at the opening of the restored building in November 2016

Who was this first American woman to legally cast a vote in a Presidential election?

Phoebe Jordan was the quintessential New Englander. Born to Emily Middlebrook and Sidney Deloss Jordan in Washington, MA, on February 26, 1864, she came to New Ashford to live with her aunt, Miss Josephine Jordan, when she was seven and never left.

Her grandfather, Francis Jordan, had arrived in New Ashford in the early 19th century. All the town’s farmers gathered to help him “raise” his house in May of 1831.

When other family members passed away Phoebe Jordan came to run the farm, which eventually grew to 400 acres. Though weighing not more than 100 pounds she did much of the work herself, having no more than two hired men to help her.

She was an expert at operating a horse-drawn mowing machine and in the winter she operated a similarly powered snow plow. She raised prize winning turkeys. She supplied the schoolhouse with its annual allotment of firewood. She was an expert marksman and killed a fox caught robbing her chicken coop with one shot at a distance of 102 feet. She never married.

For 12 years she was the owner and operator of New Ashford’s sole non-agricultural industry – a charcoal kiln, one of the last in the County – until the top of the cone caved in after a big snowstorm in 1931, burying 15 cords of hardwood.

Like her Aunt Josephine before her, she drove her heavily-laden two-horse farm wagon 12 miles to Pittsfield to sell her charcoal and farm produce. Her personal vehicle was an 1870 single-horse carriage, but her trek to the polls was usually made on foot.

So it is no surprise that this most independent and resourceful woman was a suffragist!

We are told Jordan was a suffragist, but our local newspapers at the time carried little news of local suffrage efforts, beyond running cartoons skewering women’s demands for full enfranchisement.

We do know that, long before she could vote, she was the chair of the New Ashford Republican Committee, proving that women were actively involved in politics alongside the men before the passage of the 19th amendment.

And she was a big supporter of the PR stunt that made New Ashford the first town in the nation to vote and record its election results, so it was only natural that, as soon as she could vote, she showed up bright and early at the polls.

We saw that when the Boston Globe featured a photo of Jordan and another New Ashford woman who were the first to vote, the news wasn’t that they were women, but that they were the first citizens in the USA to vote in the 1920 presidential election.

The following year Jordan enthusiastically ran for a seat on the New Ashford Board of Selectmen – and garnered exactly one vote. Women may have been grudgingly welcome at the polls but not in the seats of power.

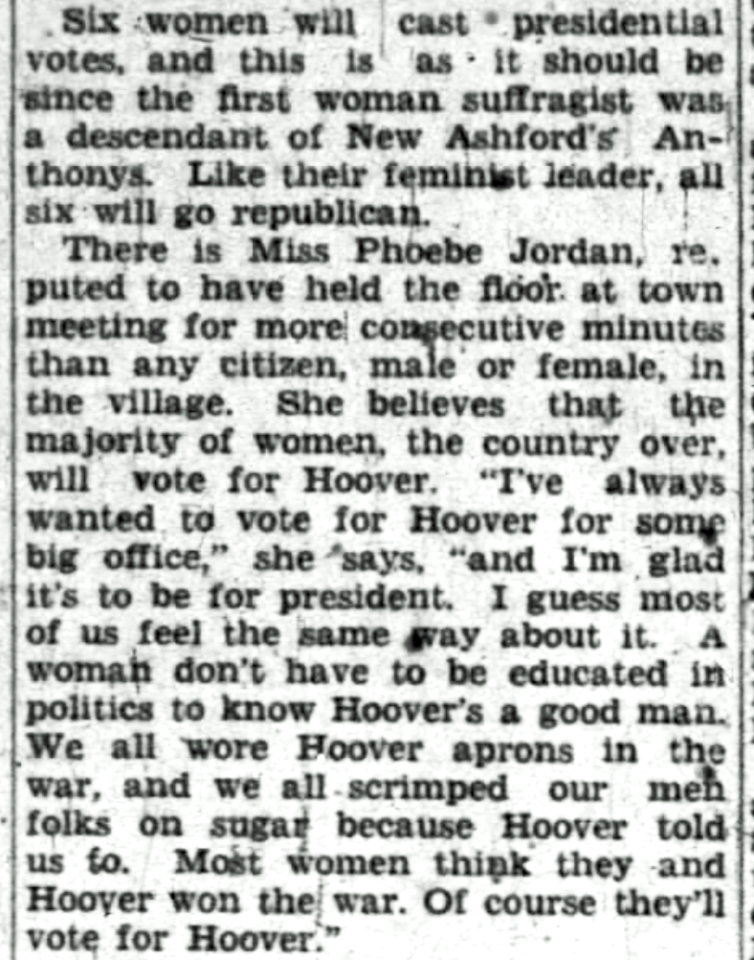

Still she continued to be a staunch Republican (see the clip from the Berkshire Eagle in July of 1928 below in which she explains at length why women support Herbert Hoover) until, in 1934, she “became dissatisfied with the manner in which the Republicans were running the state and the nation and left the party flat” after which she became “as firm a Democrat as she was a Republican” according to the North Adams Transcript.

When Jordan died in 1940 her obituary in the North Adams Transcript hailed her as the first person in the nation to cast their ballot in four consecutive presidential elections – 1920, 1924, 1928, and 1932.

It wasn’t until 1992 that she was publicly identified as the first woman to vote legally in a presidential election. And it was the effort, started in 2008, to raise money to restore the 1792 schoolhouse in New Ashford, that really began to capitalize on this feminist claim to fame for the building and the town. And it worked – in 2016 the town cut the ribbon on the restored schoolhouse and invited all living alumni to attend the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

The voting population of New Ashford turned out for a turkey supper and straw vote in advance of the 1936 presidential election, the first in which Dixville Notch, NH, usurped their status as first town in the nation to vote. Phoebe Jordan is seated in front, third from the right. The Berkshire Eagle 11-2-1936.

Susan B. Anthony

Berkshire County’s most famous suffragist is Susan B. Anthony. Although she only lived in Adams for the first six years of her life, her family roots run deep in the Hoosic Valley and she returned to the Mother City many times during her life to speak and visit relatives. Many members of the Anthony family still call this area home.

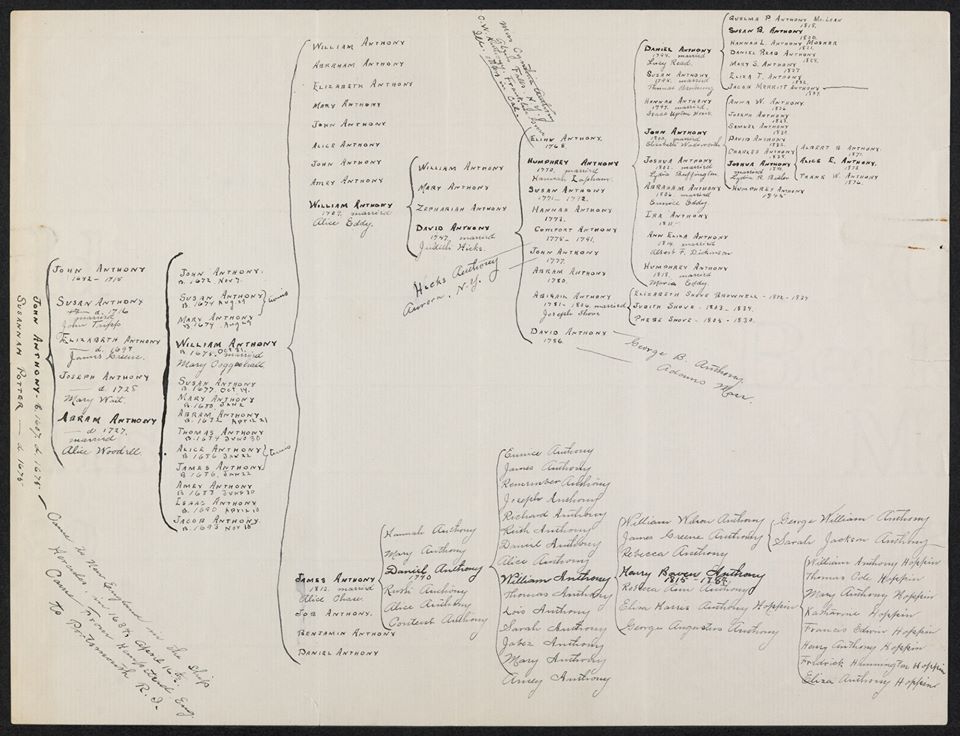

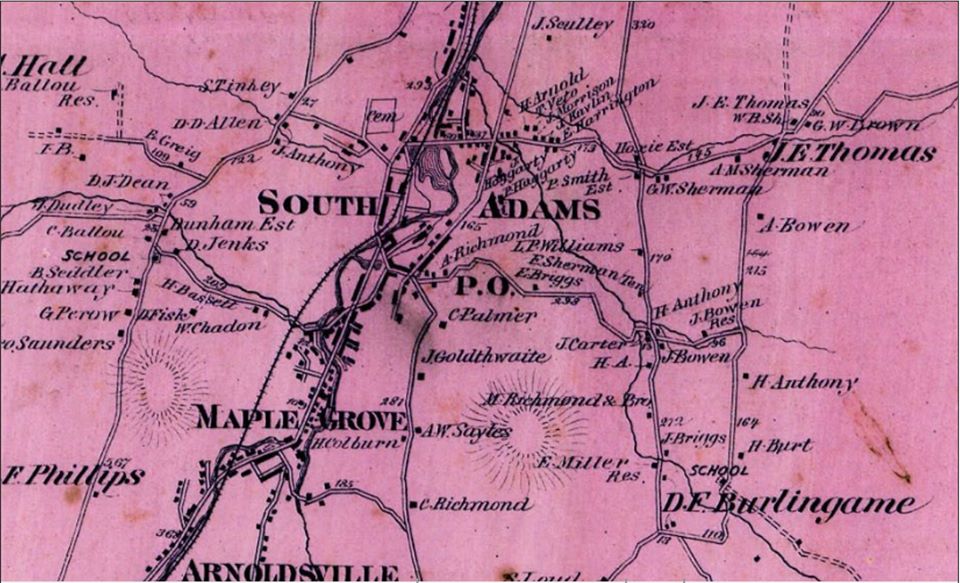

It was just before the beginning of the American Revolution that David Anthony and his wife, Judith Hicks, moved to Adams from Dartmouth, MA, bringing two little children with them (nine more were born here.) One of those two, Humphrey, married an Adams girl, Hannah Lapham. Daniel, the eldest of their nine children, born January 27, 1794, became the father of Susan B. Anthony.

Daniel Anthony’s Birthplace

The Anthonys were Quakers. Susan’s mother’s family, the Reads (also spelled Reid and Reed in various sources), were Baptists and so their ancestors first settled in Cheshire rather than Adams, where Susan’s maternal grandparents Daniel Read and Susannah Richardson were married.

It was but a few months into this marriage when the first gun was fired at Lexington and the whole country was ablaze with excitement. Legend has it that when the minister asked at the end of the Sunday service who would volunteer for the continental army, Daniel Read was the first to step forward. What his new bride thought of this is not recorded, but they did not start their family until after Daniel had fought at Quebec under Benedict Arnold in 1775, at the capture of Ticonderoga under Ethan Allen, and under Colonel Stafford, of Cheshire’s Stafford Hill, at Bennington.

Susan B. Anthony’s mother, Lucy Read, was born on December 3, 1793, one of seven children. For many years the Reads were leading members of the Cheshire Baptists, led then by Elder John Leland, who had the idea of the Mammoth Cheshire Cheese which he presented to President Thomas Jefferson on New Year’s Day of 1802. But as the years progressed Daniel Read became more and more liberal in his beliefs and became a Unitarian.

Birthplace of Lucy Read, Susan B. Anthony’s mother

Birthplace of Lucy Read, Susan B. Anthony’s mother

Susannah Read “prayed the skin off her knees” that her husband would return to the Baptist fold, but he never did, and this precipitated the family’s move from Cheshire to the Bowen’s Corners neighborhood of Adams, where they bought land adjacent to the Anthony family.

Handwritten Anthony family genealogy

The Bennington County History forum provided an interesting story: “Folklore tells us that Susan had a relative by the name of Peter Anthony. Peter Anthony was Quaker, a hermit who made his home on the western slope of a mountain outside of Bennington. One day he went out hunting and fell to death from a rock ledge. He was found many days later mangled, and frozen stiff. The Mountain was named Mount Anthony in his memory. Susan B Anthony was somehow related to him and visited Bennington in the 1850s to research family ties.”

… Continuing our look at Susan B. Anthony’s roots and how they affected her life’s work. In the 18th century there was a “state religion” in Massachusetts Bay Colony, and it was the Puritan faith that we now call the Congregational Church. As Quakers and Baptists, these families lived outside the norm in their own communities. This is why the Reads moved from the Baptist town of Cheshire to the “suburbs” of Quaker Adams when Daniel Read became a Unitarian.

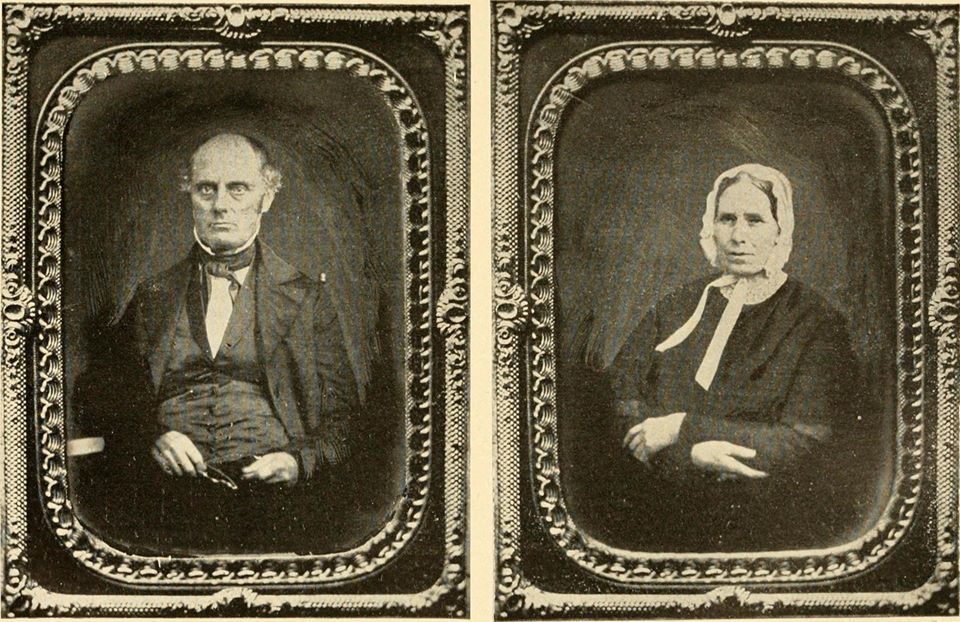

The Quakers placed great value on education for both sexes and established schools that were attended by many neighborhood children. So while Daniel Anthony (1794-1862) was a Quaker and Lucy Read (1793-1880) was a Baptist, they went to school together. Daniel was sent away to Nine Partners, a Quaker boarding school in Dutchess County, NY, and returned to teach in Adams. It was a this point that romance blossomed between the neighbors.

But Daniel was forbidden to marry “out of meeting.” While the Quakers had what we would consider very progressive ideas about women’s rights and the abolition of slavery, they did not drink, dance, sing, or wear brightly colored clothing. With the exception of the drinking, Lucy Read was an outgoing young woman who enjoyed all of the above, especially singing since she had a lovely voice. She expressed the desire to “go into a ten acre field with the bars down” so that she could sing at the top of her voice.

So for her the decision to marry was the decision to completely change her way of life. On the night four days before their wedding she went out and danced until 4 am while Daniel sat quietly outside waiting for her.

Daniel then had to face the Quaker Elders when he and Lucy returned from their wedding trip in July of 1817. That his mother was an Elder and “sat on the high seat” undoubtedly helped the couples’ cause. While the Meeting contended that Daniel told them that he was “sorry he had married” Lucy, he insisted that he had said he was “sorry that in order to marry the woman I loved best, I had to violate the rule of the religious society I revered most.”

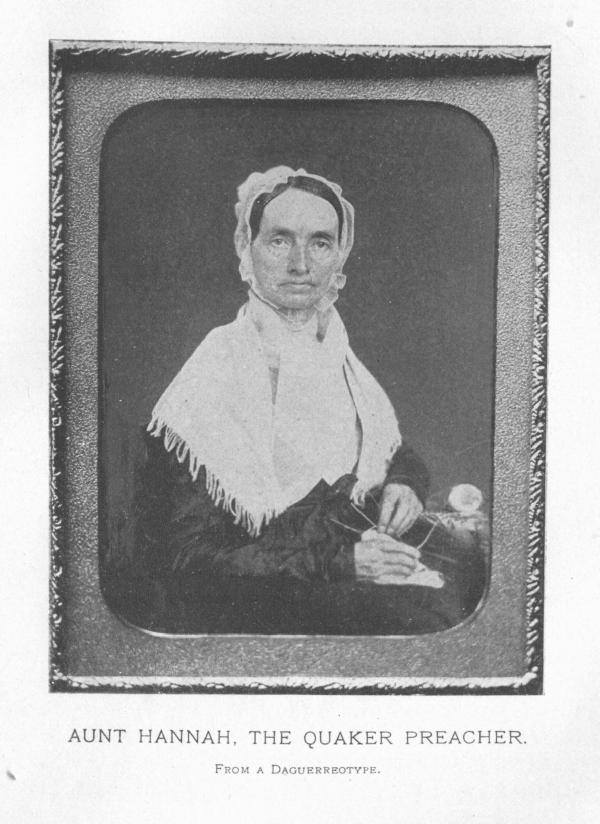

Hannah Anthony Hoxie, Daniel Anthony’s sister

Hannah Anthony Hoxie, Daniel Anthony’s sister

Susan B. Anthony was the second of Daniel and Lucy Read Anthony’s seven children. She was born on February 15, 1820, in the house that is now The Susan B Anthony Birthplace Museum on East Road in Adams. The home was built in 1818 by Daniel Anthony on land gifted to him by his in-laws, and adjacent to their property, with lumber given by his own father. Until that house was built Daniel and Lucy lived with her parents.

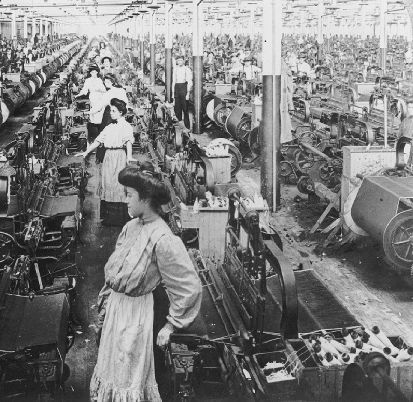

When the War of 1812 disrupted the importation of cotton cloth from England, Daniel Anthony was among the many businessmen who saw an opportunity. Hauling cotton forty miles by wagon from Troy, NY, in 1822 he built a factory of twenty-six looms power by water fed down from Tophet Brook through pipes made of hollow logs.

Millwork afforded “women of respectability” one of the first opportunities to earn money outside the home. And to preserve that respectability the millworkers, most of them young girls from Vermont, boarded in the home of the millowner.

Female mill workers in Pittsburg, PA textile mill, c. 1840s

Female mill workers in Pittsburg, PA textile mill, c. 1840s

Lucy, with three children and counting of her own, boarded eleven of the millworkers with only the help of a thirteen-year-old girl who worked for her after school hours. She cooked their meals on the hearth of the big kitchen fireplace, and in the large brick oven beside it baked crisp brown loaves of bread. From a young age Susan was helping her mother in the house and questioning her father about why his female employees weren’t given equal pay for equal work.

Homes still owned by Bowen and Anthony family members can be seen on the map below, clustered at the right. The two branches of Tophet Brook enclose the area, before running diagonally across the map (glancing off of the second A in ADAMS) to meet the Hoosic River downtown.

“Lucy Read Anthony was of a very timid and reticent disposition and painfully modest and shrinking. Before the birth of every child she was overwhelmed with embarrassment and humiliation, secluded herself from the outside world and would not speak of the expected little one even to her mother. That mother would assist her overburdened daughter by making the necessary garments, take them to her home and lay them carefully in a drawer, but no word of acknowledgement ever passed between them. This was characteristic of those olden times, when there were seldom any confidences between mothers and daughters in regard to the deepest and most sacred concerns of life, which were looked upon as subjects to be rigidly tabooed.”

– Ida Husted Harper, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Volume I 1898

Lucy Anthony gave birth to four of her eight children (six lived to adulthood) in one of the front rooms at what is now the The Susan B Anthony Birthplace Museum on East Road in Adams, MA.

Bedroom in the Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum

Their second child, Susan, was named for her mother’s mother Susanah, and for her father’s sister Susan. In her youth, she and her sisters responded to a “great craze for middle initials” by adding middle initials to their own names. Anthony adopted “B.” as her middle initial because her namesake aunt Susan had married a man named Brownell. Anthony never used the name Brownell herself, and did not like it.

The Quakers’ respect for women’s equality with men before God left its mark on her and as soon as she was old enough she went regularly to Meeting with her parents – her mother attended meeting but never became a Quaker because she felt she could not live up to their strict standard of righteousness – sitting by the big fireplace on the women’s side of East Hoosuck Quaker Meeting House in Adams. With this valuation of women accepted as a matter of course in her church and family circle, Susan took it for granted that it existed everywhere.

Daniel Anthony was a staunch Abolitionist, as were most Quakers, and he tried not to buy cotton for his mill that had been raised by slave labor. The cotton mill at Bowens Corners was very successful, and soon the family opened a store in one of the front rooms of what is now The Susan B Anthony Birthplace Museum in Adams.

Regarded as one of the most promising, successful young men in this region, Daniel soon attracted the attention of Judge John McLean, a cotton manufacturer in Battenville, NY, who was eager to enlarge his mills and saw in Daniel an able manager. Despite their parents’ distress at seeing the young family move 44 miles away, in July of 1826 Daniel, Lucy and their children climbed into a green wagon with the Judge and his grandson, Aaron, and headed northwest to Washington County.

The first year the Anthonys lived in Judge McLean’s house where there were two slaves not yet manumitted. The Anthony children had never seen black people before and Anthony’s father explained that in the South they could be sold like cattle and torn from their families. Susan was saddened by their plight.

Before she became a champion for women’s rights and suffrage, Susan was very active in the Abolitionist movement, circulating anti-slavery petitions when she was 16 and 17 years old. She worked for a while as the New York state agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society. She first met Elizabeth Cady Stanton after Stanton had attended an anti-slavery meeting at Seneca Falls. When her family moved to Rochester, NY, in 1845 she became life-long friends with Frederick Douglass.

Susan’s adult life and work are well chronicled and we encourage you to learn more during our Summer of Suffrage as we celebrate the centennial of the passage of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote. Although she had died 14 years earlier, the amendment was known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment and there is no doubt that American women owe a great debt of gratitude to this daughter of the Berkshires!

Susan B. Anthony, Image from the Library of Congress online collection

Susan B. Anthony, Image from the Library of Congress online collection

Why Not Take an Amazing American Women Road Trip?

Have you been following our Susan B. Anthony Posts? Have you watched the “Hamilton” movie? Both Anthony and Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton were born and raised in this region, and returned here many times as adults.

While the these buildings and museums remain closed or are only open for limited hours due to the pandemic, the countryside is beautiful, and many restaurants are open for take-out or outdoor dining. An Amazing American Women Road Trip can be a great antidote to quarantine times and a terrific addition to a homeschool curriculum.

The Susan B Anthony Birthplace Museum

67 East Road, Adams, MA

http://www.susanbanthonybirthplace.com/

Quaker Meetinghouse (Adams, Massachusetts)

74 Valley Street, Adams, MA

https://tinyurl.com/z9oprqm

Susan B. Anthony Childhood Home from age 13-16

2835 State Route 29, Greenwich, NY

https://tinyurl.com/ybpdfupp

The General Philip Schuyler House

4 Broad Street, Schuylerville, NY

https://www.nps.gov/sara/planyourvisit/schuyler-house.htm

With a little more driving you could visit…

The National Women’s Hall of Fame

1 Canal Street, Seneca Falls, NY

The National Susan B. Anthony House and Museum

17 Madison Street, Rochester, NY

Short Biographies

Thanks to WHM member Anne Crider for the short biographies of Outstanding Williamstown Women you will see below!

Helen Renzi (1924-2012)

Educator

The First Woman School Superintendent in Williamstown

(and all of Berkshire County)

Helen Renzi begin her 25 year career in the Williamstown Elementary school in 1961 as a 4th grade teacher. Later she was named principal, and in 1981 superintendent. She was the first women school superintendent in Williamstown and in all of Berkshire County. The elementary school named its multipurpose room after her, and each year since 1986, the Helen Renzi Award is presented to four “great kids” from the 6th grade.

Helen was a founder of the Williamstown Children’s Museum and an early contributor to the school’s integrated art program. In 1979, she was named a member of the Institute for Development of Educational Activities Academy of Fellows. She was chosen with 650 other outstanding American educators for the honor.

Born in Brooklyn and educated at West Chester (PA) University, Helen did graduate studies at Penn State University, Boston University and Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.

She and her husband, Ralph Renzi were parents of four children.

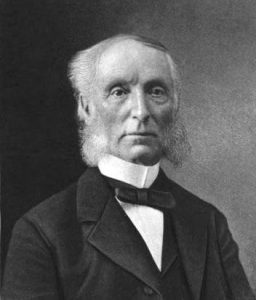

Emma Curtiss Bascom (1828-1916)

Emma Curtiss Bascom (1828-1916)

Teacher and Temperance and Woman Suffrage Activist

Emma Curtiss Bascom was one of the earliest advocates for woman suffrage and women’s rights. She was born in Sheffield, Massachusetts 1828. After her education at several different academies she taught school in Kinderhook Academy in New York and Stratford Academy in Connecticut.

In 1856 she married John Bascom, a professor at Williams College. The Bascoms lived in Williamstown for most of their marriage. She and John had five children and during the early years Emma ran their home, raised the children and helped her husband with his work during the years he was unable to read and write due to an eye ailment.

In 1874 John Bascom was appointed president of the University of Wisconsin and the family moved to Madison where they lived until their return to Williamstown in 1887. The move give Emma an opportunity for an active public life. The women in the west were more open to her ideals for woman’s advancement. She became active in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the woman’s suffrage organization. She entertained many of the most influential woman of the time including Francis Willard and Susan B. Anthony at the President’s house.

Emma worked hard for the causes in which she believed. She was a charter member of the Association for the Advancement of Women and a founding member and president of Wisconsin’s Equal Suffrage Association, the Secretary for the Woman’s Centennial Commission for the state of Wisconsin, and very active for many years in Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. On her return to Williamstown she continued to support her causes. In 1930 she was elected to the Wisconsin League of Women Voters honor roll.

Emma died February 27, 1916 and was buried in the Williams College cemetery. She shares the plot with John and four of their offspring.

Florence Bascom

Florence Bascom

Emma and John Bascom’s daughter, the second woman to earn a PhD in geology in the US, and the first woman to work for the US Geological Survey.

Bascom family monument in the Williams College cemetery.

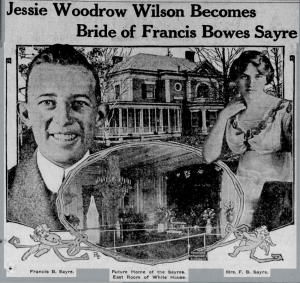

Jessie Woodrow Wilson Sayre 1887-1933

Jessie Woodrow Wilson Sayre 1887-1933

Suffragist and Political Advocate

Jessie Sayre, the second daughter of US President Woodrow Wilson, was an advocate for woman suffrage and a political activist. In 1913 after a White House wedding to Francis Bowes Sayre and a European honeymoon, the couple settled in Williamstown. Francis Sayre, a Williams College and Harvard Law School graduate, worked as an assistant to Williams College president Harry A. Garfield. Jessie Sayre, the mother two young children, found time to be the president of the Williamstown branch of the Equal Suffrage League, hosting meetings at her home and speaking at Berkshire County League meetings.

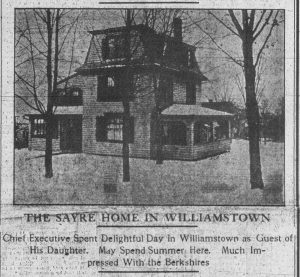

Much to the delight of the townspeople the Sayre house on Main Street, currently a B&B known as The House on Main Street, was visited on a number of occasions by President Wilson, including Thanksgiving in 1914 and the christening of the Sayre’s second child in 1916. In fact he was visiting when he learned that he had been elected for a second term.

Sayre house at 1120 Main Street

Wilson visits Williamstown headline

Wilson visits Williamstown headline

courtesy of Saturn Leonesio

After the end of WWI the Sayres moved to Cambridge, MA where Francis was offered a faculty position at Harvard Law School. Jessie continued her active interest in the League of Women Voters, the League of Nations Association, and also established a prominent role in the Massachusetts Democratic Party. In 1928 she introduced presidential nominee Al Smith at the Democratic National Convention, and in 1930 she was approached to run for the Senate. She took herself out of consideration in order to remain at home with her family and concentrate on her role as secretary of the Massachusetts Democratic Party.

Jessie died at the age of 45 following abdominal surgery. The Boston Globe expression of sympathy noted that ” Mrs. Sayre was a public character and had won for herself the respect and affection of the community. Although she had never held public office she was one of the most useful citizens in her adopted State.”

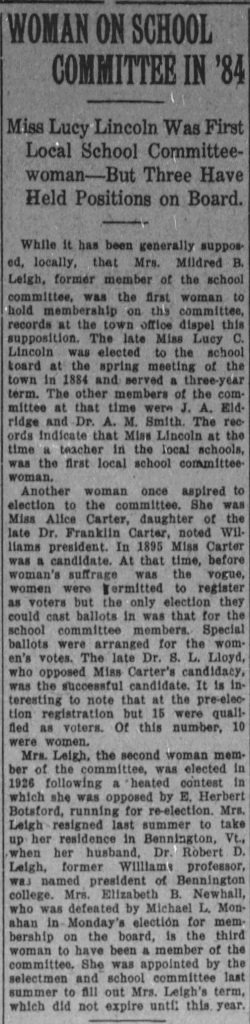

Lucy C. Lincoln (1828-1911)

Lucy C. Lincoln (1828-1911)

First Woman to be Elected to Office in Williamstown

Lucy C. Lincoln was born Lucy Phillips on September 9, 1828 in Windsor. A sister of John Phillips, a professor of Greek at Williams, she married Isaac N. Lincoln, Williams College professor of Latin, in 1851. Unfortunately, Isaac died in September of 1862, at the age of 36, after a visit to Plainfield to attend to his brother who had been ill and died while Isaac was visiting. After his brother’s death, Isaac stopped at his father in law’s home in Windsor and became ill with typhoid fever. He died after an illness of two or three weeks. Interestingly, in 1856, several years before his death, Isaac Lincoln was elected to the School Committee as his wife would be, nearly thirty years later. At the annual town meeting held in March of 1884, Lucy Lincoln was elected to the School Committee for a three year term. Mrs. Lincoln relocated to New York and died there in 1911. There is no mention of her achievement as the first female elected official in Williamstown in her obituary.

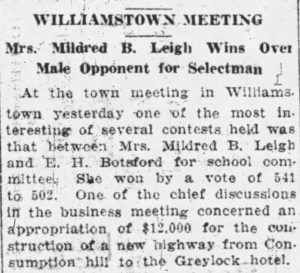

Mildred Boardman Leigh 1894-1959

The Second Woman to be Elected to Office in Williamstown

In 1868 women were elected to serve on school committees in a few Massachusetts towns, but it was not until 1879 that the Legislature voted to allow women to vote for school committee members, male or female. And it wasn’t until 1926 that a woman was elected to the Williamstown school committee. By 1926 of the 355 school committees in the state, 256 had women members and a total of 269 women were on school committees.

In 1926 a citizen’s petition was circulated in Williamstown stating that it was time to have a woman on the school committee and endorsing Mrs. Robert Leigh. Mildred Leigh was a founding member and the president of the newly formed Williamstown League of Women Voters. She won the close contest for the position, defeating E. Herbert Botsford by a margin of 541 to 502.

Mildred Leigh resigned from the committee in 1928 after her husband, Dr. Robert D. Leigh, a professor of political science at Williams College, was named the first president of Bennington College. She assisted her husband in planning the Bennington College program and its operations.

Mildred Leigh, nee Boardman, was born in Rochester, NY and received bachelors and masters degrees from Teacher’s College of Columbia University. She taught in public schools in western New York, at Bennett College, Millbrook, NY, and at Reed College, Portland, Oregon. She died May 19, 1959.

Katherine Slater Haskell Wyckoff (1900-1993)

Katherine Slater Haskell Wyckoff (1900-1993)

First woman elected to the Board of Selectmen in Williamstown and in all of Berkshire County

Back in 1921 Phoebe Jordan of New Ashford, the first woman to vote legally in a US Presidential election, ran for the Board of Selectmen in her town and received exactly one vote. We have no record of how many women in Berkshire County subsequently tried over the years, but it wasn’t until 1960 when a woman actually served on a Board of Selectmen, and it was Katherine “Kay” Wyckoff of Williamstown, referred to in the press as “Mrs. Williamstown.”

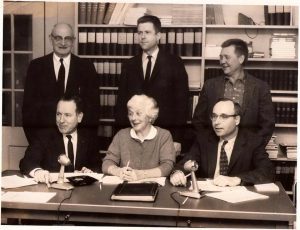

Kay Wyckoff is seated in the center as a member of the Select Board

Kay Wyckoff is seated in the center as a member of the Select Board

Wyckoff was elected to the Board in 1961, but she was first appointed to fill an unexpired term in 1960. There was much town debate prior to her appointment as the rumor mill churned over the questions such as: “Was the town ready for a woman on the Board?” “Were there any qualified women in town?”

Other names were put forward before Wyckoff’s but those women declined the appointment, as indeed Wyckoff did at first, but at the urging of friends and community members she changed her mind, stating, “I do believe that a woman can effectively serve in a situation of this kind without slighting her home duties, and after reconsideration and much mature thought I have agreed to accept the appointment.”

After serving both the term she was appointed to fill and the term she was elected to, Wyckoff declined to run again in 1963. The next woman to be elected to the Williamstown Board of Selectmen was Faith Scarborough in 1978.

Faith Scarborough

Faith Scarborough

Born in New York City in 1900, Wyckoff served as a yeoman first class in the Navy in the Cable Censor Office in the city during World War I. In 1919 she moved with her birth family to Ithaca, NY, were she attended Cornell University, graduating in 1923.

A first marriage that ended in divorce took her to southern California, where she became involved with the PTA at her children’s school, eventually taking a job as assistant purchasing agent for the Compton High School and Junior College Union, comprising five schools, along with serving as president of the Lynnwood Coordinating Council.

In 1946 she married William O. Wyckoff and moved to Williamstown when he became Director of Placement at the College.

Here Wyckoff became heavily involved with the Williamstown League of Women Voters, serving as president as well as in other capacities. She also served on the boards of the Williamstown Bicentennial Committee, the Visiting Nurse Association, the Williamstown Community Chest, and North Adams Regional Hospital, among others. In 1958 she was appointed as an interim member of the town’s Capital Outlay Committee.

Wyckoff seated at far right as Eleanor Bloedel cuts the cake celebrating the third anniversary of the Women’s Exchange.

Wyckoff seated at far right as Eleanor Bloedel cuts the cake celebrating the third anniversary of the Women’s Exchange.

In 1957 Wyckoff, Eleanor Bloedel, and other women of the town started the Women’s Exchange to benefit the Visiting Nurse Association. Wyckoff served as managing director of the Exchange until 1987.

Wyckoff was the first recipient of the Faith Scarborough Citizenship Award in 1982. She also received the Williamstown Community Chest Award in 1988.

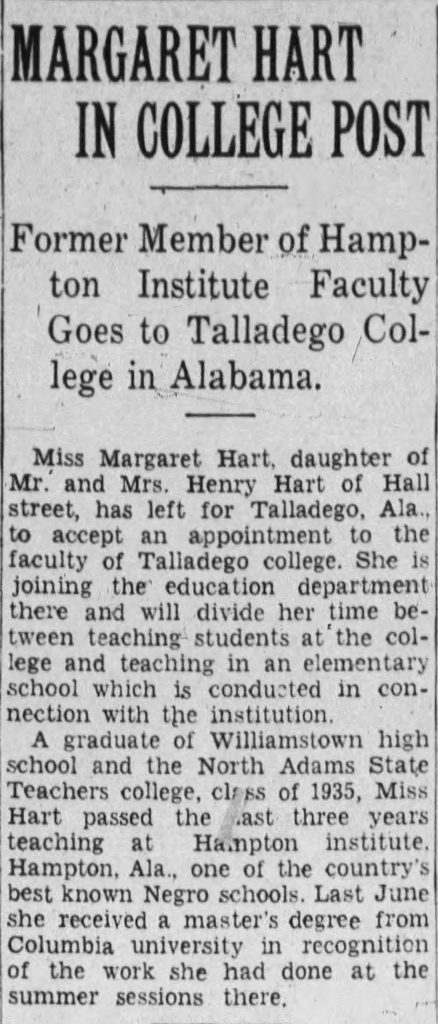

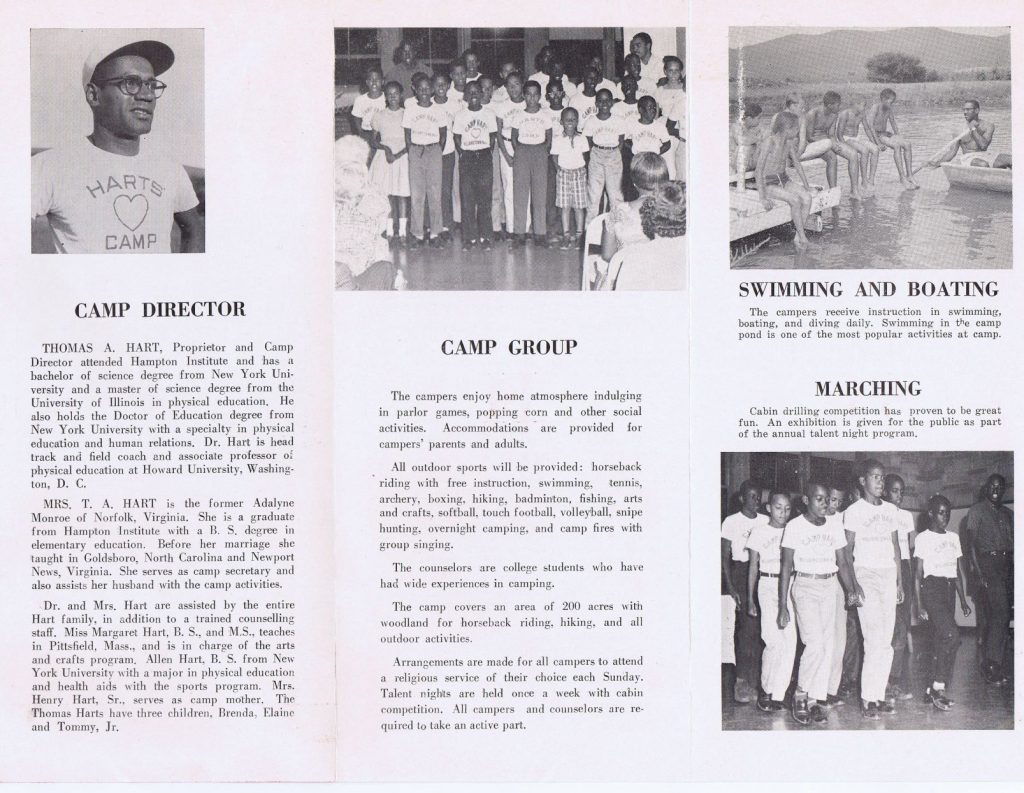

Margaret Hart (1911-2004)

First African American graduate of North Adams State Teachers College

Margaret Hart was the daughter of Henry Hart and his wife, Kate Alexander, both of whom came to Williamstown from North Carolina. Henry began a trucking business that later became a construction company; Kate worked at the Sand Springs Hotel and took in washing from college students to earn money.

Margaret obtained a master’s degree from Columbia University Teachers College in 1930 and her career included teaching at the Hampton Institute Training School and at public schools in Indiana and Alabama. She later returned to live in Williamstown and taught for 26 years at North Junior High School (now Reid Middle School) in Pittsfield.

Beginning in 1947, her family owned and operated Hart’s Camp for boys on 200 acres in South Williamstown where Margaret assisted her brother, Thomas, the camp director.

In 1996, she received an honorary doctor of pedagogy degree from North Adams State College, and in 2000 her alma mater, now known as Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts, established the Margaret A. Hart Scholarship Fund to honor her outstanding contributions in teaching and community service. She is remembered as a friend to the neighborhood children; an inspiring role model and mentor to many students over the years; and as a gracious, elegant woman dedicated to helping improve the lives of others. Her portrait was included in a mural of prominent African American citizens that was placed in Pitt Park in Pittsfield in 1995. In addition to her long teaching career, Ms. Hart was a lifetime member of the NAACP and of the First United Methodist Church of Williamstown. Margaret Hart died in 2004 at the age of 92.

League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV) nationally and our very active local branch here in Williamstown grew out of the woman suffrage movement. Thanks to historian Barbara Winslow and Anne Skinner, current president of the Williamstown League, for their help and enthusiasm.

You can learn more about the information shared here by reading Barbara Winslow’s article, The League of Women Voters: A Century of Voter Engagement, published by the The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

Read the full article: https://tinyurl.com/y2v6q9rb

Barbara Winslow is professor emerita of history at Brooklyn College. An authority on women’s activism, she is the founder and director emerita of The Shirley Chisholm Project. She is the author of Clio in the Classroom: A Guide for Teaching US Women’s History (Oxford University Press, 2009) and Shirley Chisholm: Catalyst for Change (Westview Press, 2013). With Julie A. Gallagher, she is the co-editor of Reshaping Women’s History: Voices of Nontraditional Women Historians (University of Illinois Press, 2018).

Here Winslow provides us with an overview and an introduction to the League:

“The League of Women Voters was founded in 1920 by American suffragists, just months before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the constitutional right to vote after more than seventy years of struggle.

Over the past one hundred years the League, following in the progressive politics of its mother organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), has been an influential and powerful women’s coalition.

An activist, grassroots organization, the League believes that citizens should play a critical role in civic advocacy. Its founders believed that maintaining a nonpartisan stance would protect their fledgling organization from becoming mired in the party politics of the day. However, League members were encouraged to be political themselves by educating citizens about, and lobbying for, governmental and social reform legislation.

The League’s accomplishments, failures, challenges, and ups and downs reflect the trajectory of US reform politics, class and racial conflicts, and the ebb and flow of women’s and feminist movements.”

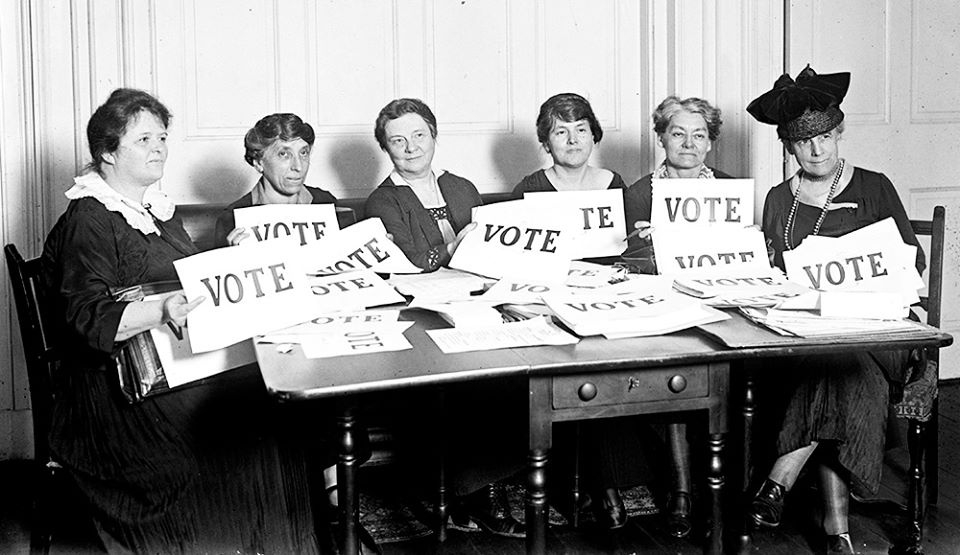

National League of Women Voters, September 17, 1924. (National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress).

National League of Women Voters, September 17, 1924. (National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress).

The national League of Women Voters (LWV) was born with a sense of urgency, mission, and apprehensive optimism.

The genesis of the League was in the West. In 1909, at the NAWSA convention in Seattle, Washington, suffragist Emma Smith DeVoe (1848-1927) proposed a national league of women voters. The conference rejected the motion. After Washington State voted to enfranchise women, DeVoe organized the National Council of Women Voters, a nonpartisan coalition of women from voting states.

Emma Smith DeVoe by James & Bushnell, ca. 1915. (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress).

Emma Smith DeVoe by James & Bushnell, ca. 1915. (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress).

Prior to the 1919 NAWSA convention in St Louis, the association’s president, Carrie Chapman Catt (1859-1947), began negotiating with DeVoe to merge her organization with a new league that would be the successor to NAWSA. As fifteen states had already ratified the Nineteenth Amendment, NAWSA wanted to move forward with a plan to educate women on the voting process and further their participation in the political arena.

Carrie Chapman Catt, ca. 1908. (Carrie Chapman Catt Papers, Library of Congress)

Carrie Chapman Catt, ca. 1908. (Carrie Chapman Catt Papers, Library of Congress)

The formal organization of LWV was drafted at the February 1920 National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) convention held in Chicago. For one year, the League was a committee of NAWSA before it became its own independent entity.

Not all NAWSA members supported the formation of the League. Some argued that since NAWSA’s goal of securing the vote was accomplished, NAWSA could be disbanded. Others were concerned that an independent organization of women might create dissension within and take women out of the existing political parties. Others were mindful of the growing conservative climate that was hostile to any form of radicalism, including feminism.

Catt promised that this new organization would be “a living memorial . . . dedicated to the memory of our brave departed leaders, to the sacrifices they made for our cause.” A League, she continued, was necessary so that women could “use their new freedom to make their nation safer for their children and their children’s children.”

From “The League of Women Voters: A Century of Voter Engagement.” by Barbara Winslow, published by The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Read the full article: https://tinyurl.com/y2v6q9rb

“What should be done, can be done; what can be done, let us do.” – Carrie Chapman Catt

After the League of Women Voters (LWV) was formally organized in February 1920, Maud Wood Park was elected the first president. The League’s first major legislative victory was the passage of the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921, which provided federal funds for maternity and child welfare.

Portrait of the National League of Women Voters’ board of directors, including Maud Wood Park and Carrie Chapman Catt, taken during its Chicago Convention in 1920.

Portrait of the National League of Women Voters’ board of directors, including Maud Wood Park and Carrie Chapman Catt, taken during its Chicago Convention in 1920.

The League’s platform was ambitious and progressive, advocating, for example, support for the Cable Act supporting independent citizenship for married women, which became law in 1922, ensuring that a woman’s citizenship did not rely on the status of her husband’s citizenship.

File Photo by Library of Congress Mrs. Maud Wood Park extending her thanks to Congressman James R. Mann, for his part in pushing the Woman’s Suffrage Constitutional Amendment through the House of Representatives.

File Photo by Library of Congress Mrs. Maud Wood Park extending her thanks to Congressman James R. Mann, for his part in pushing the Woman’s Suffrage Constitutional Amendment through the House of Representatives.

The League also sponsored a “get out the vote” campaign and called for legislation supporting collective bargaining, child labor laws, a minimum wage, a state employment service, and compulsory public education.

By 1924 there were national branches in 346 of 433 congressional districts. One of the branches founded in 1924 was here in Williamstown.

The League of Women Voters continued its progressive legislative agenda throughout the decades. Its membership declined during the 1929−1940 Depression…But the League remained committed to progressive legislation, supporting most of the policies and proposals initiated by Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Celebrating the 10th anniversary of the LWV in 1930.

Celebrating the 10th anniversary of the LWV in 1930.

From its inception, the League was internationalist. Its founding members had been involved in a wide range of global suffrage, temperance, peace, and social welfare organizations. In the 1920s the LWV supported the League of Nations. In the 1930s it warned of the dangers of fascism, supported Roosevelt’s Lend Lease, the war aims of World War II, and, postwar, the United Nations. Harry Truman invited the League of Women Voters to serve as a consultant to the US delegation at the United Nations Charter Conference in 1945. To this day, the League maintains its presence at the United Nations through its one official and two alternate observers.

President Harry Truman invited the League to serve as a consultant to the U.S. delegation at the United Nations Charter Conference.

President Harry Truman invited the League to serve as a consultant to the U.S. delegation at the United Nations Charter Conference.

In the post–World War II era, the League of Women Voters began to make serious changes in its activities and policies. The civil rights, women’s, and social justice movements galvanized the League’s reassessment.

As early as the 1950s state chapters began to challenge restrictive voter registration laws. While much attention has been given to the racist voting laws in the southern states, northern states’ voter laws were also reprehensibly restrictive. In the 1950s the New York State League of Women Voters mounted a campaign called Permanent Personal Registration (PPR) to make voter registration easier. The New Yorker described this campaign as “the greatest political effort since the fight for woman’s suffrage.” As of 1960, in New York State one had to pass an English written and oral literacy test and provide proof of an eighth-grade education. The League fought against these racist and xenophobic restrictions.

The postwar women’s movement changed the League’s membership and political direction. It had to compete for members and political influence with organizations such as the National Organization for Women (NOW). The League reversed its position on the ERA and, after 1974, became a major partner with NOW in championing the amendment.

The LWV sponsored the United States presidential debates in 1976, 1980, and 1984, but pulled out in 1988 after refusing to go along with the demands of the major candidates’ campaigns.

The League continues to provide voters with nonpartisan information about federal, state, and local candidates as well as information on the political issues of the day.

The League of Women Voters’ membership has tripled since 2016; it now has more than 500,000 members in approximately 700 state and local organizations. It is still overwhelmingly white and middle class, but more working women are members. Especially in urban areas, the League chapters make attempts at diversity.

While still nonpartisan, the League champions a very progressive agenda including support for reproductive rights, gun safety, abolition of the death penalty, universal health care, childcare, enforcement of the EPA, and legislation combating climate catastrophe; it opposes racial profiling and economic, racial, and gender inequality. The League is also committed to universal suffrage. It opposes voter suppression in any and all forms, Citizens United, and gerrymandering; it supports federal legislation guaranteeing every eligible voter the right to vote as well as voting rights for those incarcerated and for those out of prison.

While it is a very different organization today than the one founded in 1920, the twenty-first-century League of Women Voters has fulfilled much of its century-old mission.

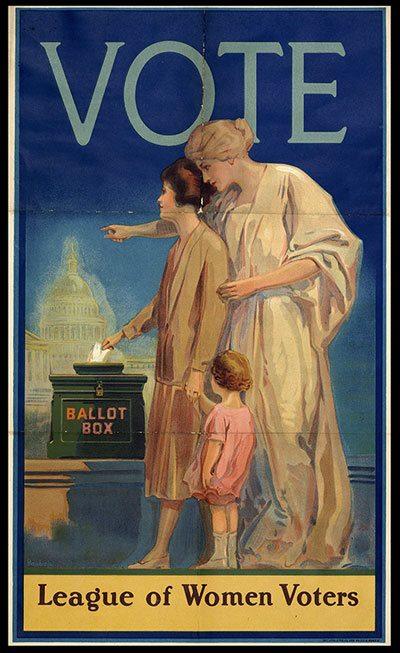

“Vote” LWV poster c 1920 by Louis Bonhajo.

“Vote” LWV poster c 1920 by Louis Bonhajo.

“Our Turn” LWV poster c 2018 by Laura Champion from Lafayette High School.

“Our Turn” LWV poster c 2018 by Laura Champion from Lafayette High School.

Learn more about the information shared here by reading Barbara Winslow’s article, “The League of Women Voters: A Century of Voter Engagement,” published by the The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Read the full article: https://tinyurl.com/y2v6q9rb

Barbara Winslow is professor emerita of history at Brooklyn College. An authority on women’s activism, she is the founder and director emerita of The Shirley Chisholm Project. She is the author of Clio in the Classroom: A Guide for Teaching US Women’s History (Oxford University Press, 2009) and Shirley Chisholm: Catalyst for Change (Westview Press, 2013). With Julie A. Gallagher, she is the co-editor of Reshaping Women’s History: Voices of Nontraditional Women Historians (University of Illinois Press, 2018).

As a community, Williamstown was anti-Suffrage, but once the 19th amendment was ratified and the League of Women Voters was established in 1920, the women of the town were fairly quick to form a LWV branch. Founded in 1924, the Williamstown League is now one of the oldest in the state as earlier branches have gone by the wayside.

“We are a grassroots organization,” Anne Skinner, a long-time League member and its current President explained. “The programs that we support come from the opinions of the members of the league. You’re not just paying your dues, you pay your dues and then you think about the issues.”

Voter education is a high priority, and it is League members who hand out the “I Voted” stickers as you exit the polls, although they haven’t been able to this year. Skinner reminded all voters that the primary for state offices is on September 1st. “It’s very early this year, and the League is urging people to vote by mail.”

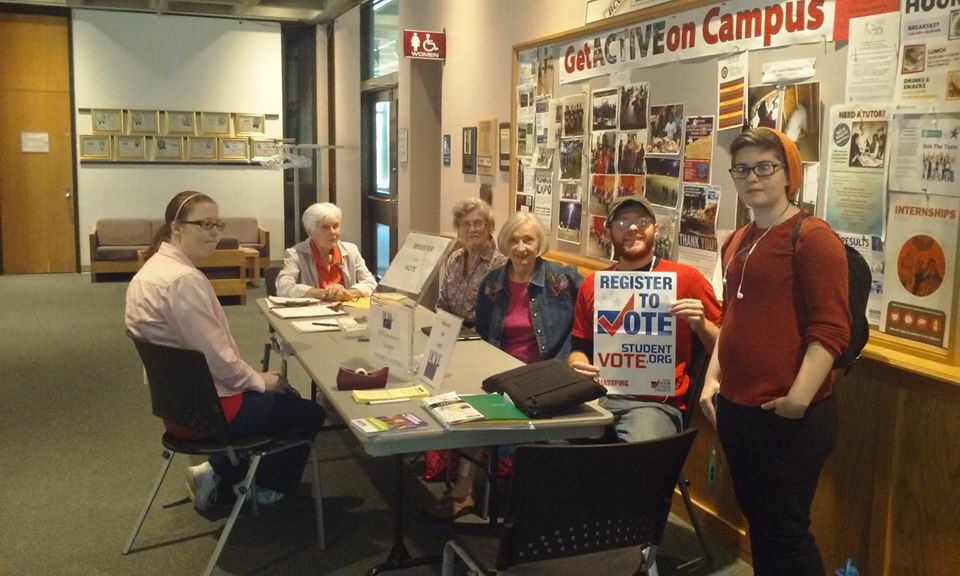

LWV members holding a Voter Registration Drive at BCC in 2015

LWV members holding a Voter Registration Drive at BCC in 2015

The Williamstown League has proudly hosted candidate forums over the years to enable residents to get to know candidates on both sides of the aisle and the issues. “We’re very proud of our non-partisanship and we don’t endorse candidates or issues we haven’t studied,” Skinner said. “We also hold two ballot question issue forums every election cycle, one for the questions we support and one for those we don’t.” iBerkshires photo of Anne Skinner introducing Paul Caccaviello, Judith Knight and Andrea Harrington, the 2018 candidates for Berkshire County District Attorney, at a League sponsored forum.

iBerkshires photo of Anne Skinner introducing Paul Caccaviello, Judith Knight and Andrea Harrington, the 2018 candidates for Berkshire County District Attorney, at a League sponsored forum.

Last June League members helped plant a tree outside the Milne Public Library Williamstown in honor of Massachusetts ratifying the 19th amendment in June 1919. “Our tree and its plaque are just to the left of the Library entrance and it is thriving.”

Service berry tree in bloom in 2020, one year after planting

Service berry tree in bloom in 2020, one year after planting

Continuing that celebration, about 70 Williamstown League members, all dressed in white, marched in last year’s 4th of July Parade. “We got shortchanged because we couldn’t march this year in honor of the League’s 100th anniversary, but we will celebrate the 101st in style next year,” Skinner proclaimed. “We want to get young people carrying signs saying ‘I’m going to vote in 2024.'”

League members Barbara Winslow, Bette Craig, and Carrie Waara making posters for the 2019 4th of July parade.

League members Barbara Winslow, Bette Craig, and Carrie Waara making posters for the 2019 4th of July parade.

iBerkshires photo of Williamstown LWV members marching in the 2019 4th of July Parade.

iBerkshires photo of Williamstown LWV members marching in the 2019 4th of July Parade.

Thanks to Gene and Justyna Carlson of the North Adams Museum of History & Science for providing this program from the 1913-1914 North Adams Equal Suffrage League. The quotations are particularly interesting.

And thanks to Anne Crider for the following information on the League: “The North Adams Equal Suffrage League existed for 14 years before it disbanded in August of 1920. It was formed by Katherine Millard, who was chosen as president and held the position for the entire time the League existed. Another active woman in the League was Mrs. Condit W. Dibble.”

Other Outstanding Women of Williamstown

Margaret Lindley

Margaret Lindley

1900-1966

Although born in North Adams, Margaret Jones was educated in the Williamstown public schools, the place where she would build her career as an adult.

She graduated from the North Adams Normal School (now MCLA) and married Laurence Lindley, a self-employed carpenter, before starting her teaching career in Williamstown at the Broad Brook School in 1919, She then taught at the Mitchell School until her retirement in 1960, serving two years as principal.

At the time of her retirement she was voted “Teacher of the Year” by the Grant-Mitchell PTA at a dinner celebrating her 41 year career, held at the 1896 House. John Bennett Perry (WHS class of 1959, son of Alton L. Perry and father of “Friends” star Matthew Perry) led a chorus of “Peg of My Heart” and sang two solos.

Even in retirement, Margaret Lindley couldn’t stay out of the classroom, serving as a substitute teacher at Mt. Greylock Regional High School.

She was a member of the Sigma Chapter of Delta Kappa Gamma, an honorary teachers sorority, and a member of the Mountain Chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star.

St. John’s Episcopal Church was packed for her memorial service in 1966 with teachers and retired teachers from the Williamstown Elementary School and Mt. Greylock, the Selectmen and Town Manager, businessmen, and friends in attendance.

The following year the town purchased 13.5 acres at the southern junction of Routes 7 & 2 from Michael Nicholas, owner of the Taconic Park Restaurant for use as a “municipal swimming pool and picnic area” to be known as Margaret Lindley Park.

Taconic Park (Abe’s Swimming Pool), c. 1960

Taconic Park (Abe’s Swimming Pool), c. 1960

Margaret Lindley Park

Margaret Lindley Park

Abolition and Woman Suffrage Stars – Angelina and Sarah Grimké

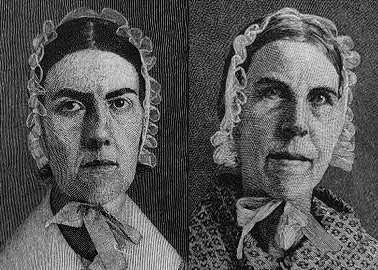

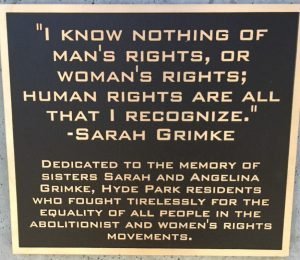

Ruth Bader Ginsburg famously said, “I ask for no favor for my sex. All I ask of our brethren is that they take their feet off our necks,” but she is not the originator of this phrase. That was Sarah Moore Grimké (1792-1873) who, along with her sister Angelina Emily Grimké Weld (1805-1879), was a leading voice in abolitionist and suffragist circles.

Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah Grimké

Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah Grimké

In 1836 Angelia published the abolitionist tract “An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South,” followed by Sarah’s “A Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern States.” In their native state their books were burned and their mother was informed that her daughters would be arrested if they dared to return home.

The following year Angelina and Sarah traveled around New England speaking on the abolitionist circuit, at first addressing women only in large parlors and small churches. Their speeches concerning abolition and women’s rights reached thousands.

Early in 1838 Angelina became the first woman in U. S. history to address a legislative committee when she was invited to speak to the Massachusetts Legislature in the Boston State House.

In 1838, Angelina married Theodore Weld, a leading abolitionist who had been a severe critic of their inclusion of women’s rights into the abolition movement.

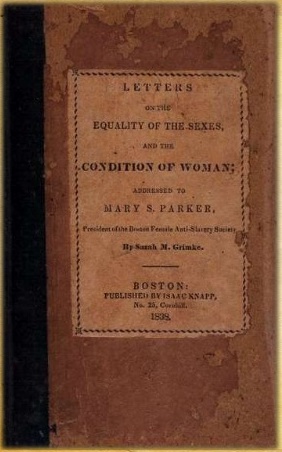

The same year Angelina married, Sarah’s letters to Mary S. Parker, President of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, were published as “Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Woman”. Later in the 19th century, these writings influenced suffrage workers such as Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott.

A PDF version of the “Letters…” is available here: https://tinyurl.com/y3bwe5c3.

A PDF version of the “Letters…” is available here: https://tinyurl.com/y3bwe5c3.

After Angelina’s marriage the Welds, their three children, and Sarah Grimké lived in New Jersey where they earned a living by running two schools. After the Civil War ended, the household moved to Hyde Park, Massachusetts, where they spent their final years. Angelina and Sarah were active in the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association.

In 1870 the sisters marched with a group of 42 women through a snow storm and a crowd of angry men to cast their votes in the general election in Lexington, MA. They weren’t arrested because of the advanced ages (65 & 77) and their votes weren’t counted, but the Grimké sisters were the the first women to vote in Massachusetts.

Dedicatory plaque on the Grimké Sisters Bridge over the Neponset River in Hyde Park, MA.

Dedicatory plaque on the Grimké Sisters Bridge over the Neponset River in Hyde Park, MA.

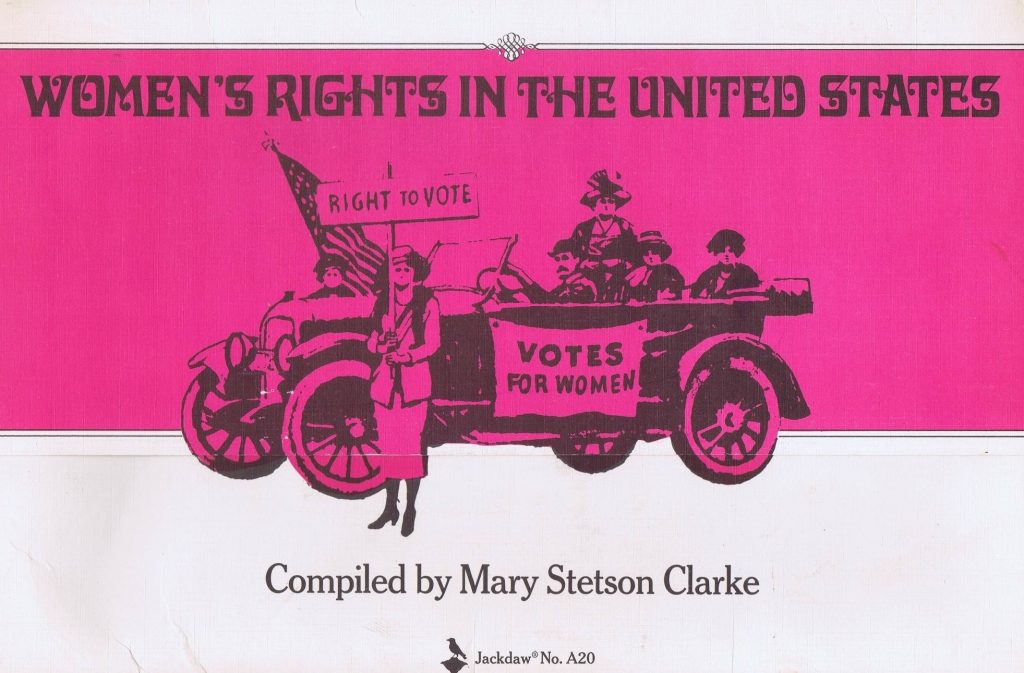

Mary Stetson Clarke’s Informative Review of “Women’s Rights in the United States”

Our friend, neighbor, and former WHM board member, Susan Stetson Clarke, has kindly shared with us the 1974 issue of The Jackdaw, focusing on women’s rights and penned by her mother, Mary Stetson Clarke (1911-1994).

“My mother was good at everything she did,” Susan Clarke recalled. “She was a wonderful housewife, a seamstress, a knitter, and then, when we were older, a writer and historian.”

Before we delve into the publication, let’s take today to get better acquainted with Mrs. Clarke.

Mary Stetson Clarke, 1911-1994.

Mary Stetson Clarke, 1911-1994.

Mary Stetson Clarke was born and brought up in Melrose, MA, where she was active in community affairs, a former member of the Conservation Commission, and a trustee of the Melrose Public Library, and on the board of the Melrose Historical Society. Other memberships included the American Association of University Women, New England Historic Genealogical Society, the Middlesex Canal Association, Massachusetts Library Trustees Association, and the Stetson Kindred of America.

She graduated from Boston University College of Liberal Arts, B.A. 1933, and was elected to its Collegium of Distinguished Alumni in 1976. She dd graduate study at Columbia University 1937-38.

After graduation from college she worked for four years on the staff of a Boston newspaper. She was married in 1937 to Edwin L. Clarke, an electrical engineer, who retired from MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory where he worked on research projects.

Following marriage and the birth of three children she wrote feature articles for various newspapers and magazines. When her children were in their teens she began writing historical novels. Later she wrote historical nonfiction, for children and for adults. She taught creative writing at the Boston Center for Adult Education, 1958-60; and was a research secretary at Harvard University, 1960-64.

Mrs. Clarke was the author of twelve books of historical fiction and nonfiction: Petticoat Rebels, The Iron Peacock, Pioneer Iron Works, The Limner’s Daughter, The Glass Phoenix, Piper to the Clan, Bloomers and Ballots, Immigration in Colonial Times, Women’s Rights in the United States, The Old Middlesex Canal, A Visit to the Iron Works, Iron in Colonial Times. Several received favorable reviews in the New York Times, The Glass Phoenix was a Junior Literary Guild book. Pioneer Iron Works was reprinted by the National Park Service which used the book as a text for its guides.

The Old Middlesex Canal is considered the definitive work on the subject.

“On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the publication of her book on the Middlesex Canal I went and spoke about my mother and her work, wearing an outfit that she had made me,” Susan Clarke recounted with pleasure.

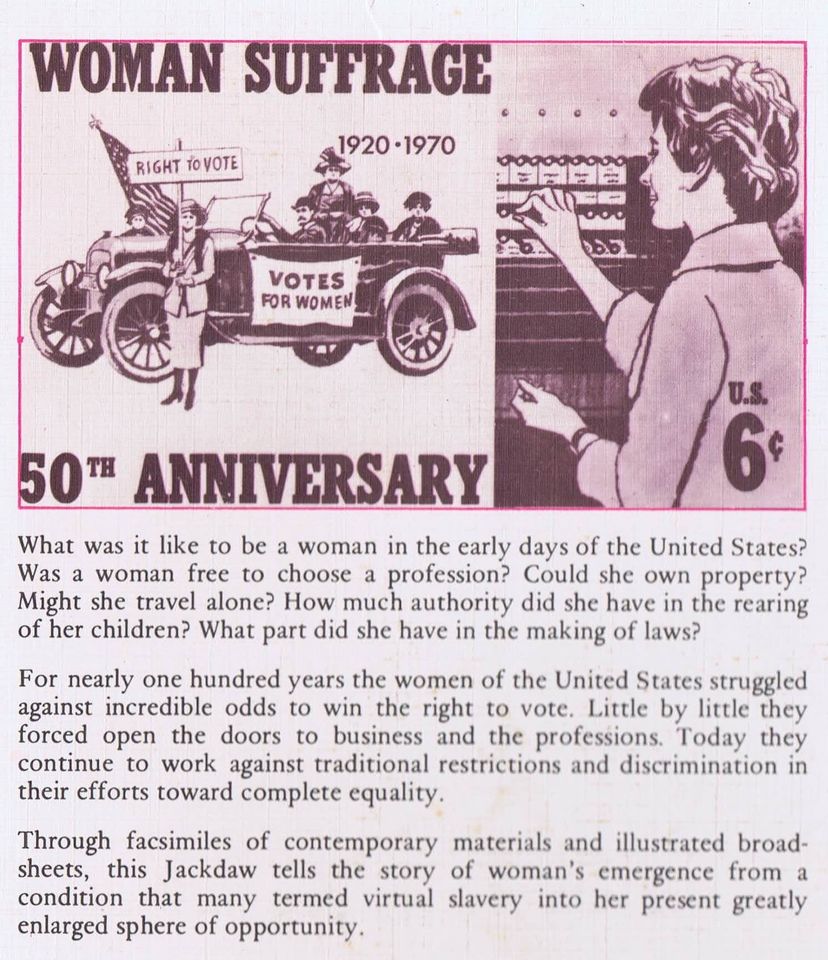

Let’s delve into our 1974 edition of The Jackdaw, compiled by Mary Stetson Clarke.

The opening pages contain some interesting images and postage stamps celebrating early suffragists: Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, Carrie Chapman Catt, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Livermore, Grace Greenwood (aka Sara J. C. Lippincott), Anna E. Dickinson, and Lydia M. F. Child.

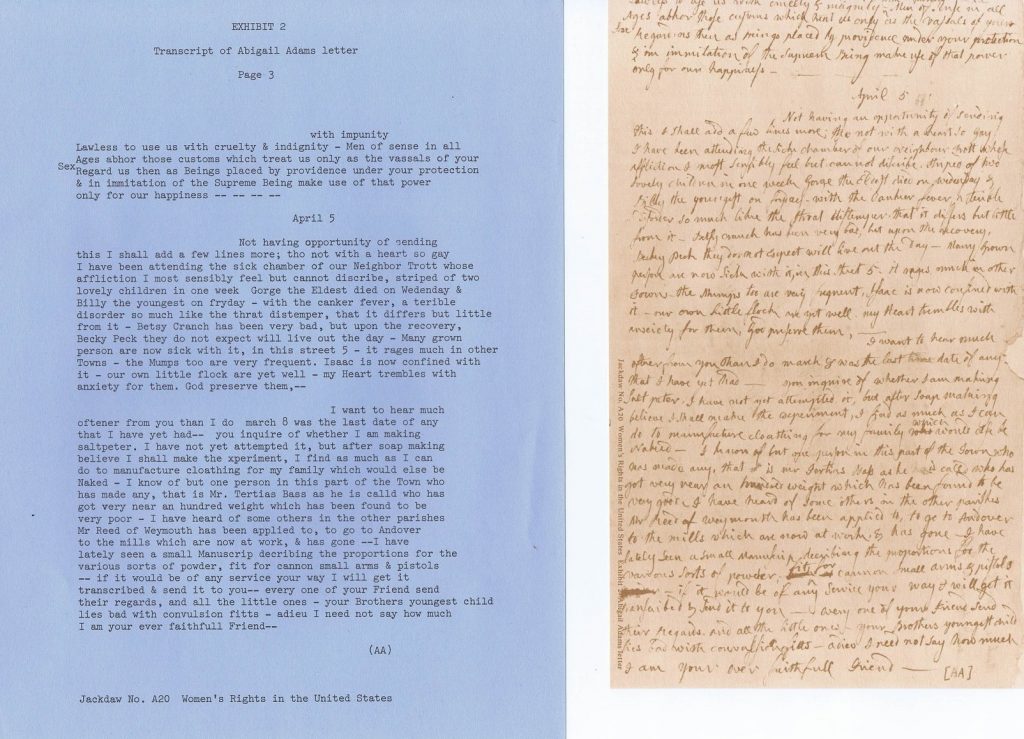

The introduction and table of contents set the tone for the 50 anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment, and whets our appetites for what is to come – letters from Abigail Adams and Susan B. Anthony, news from Seneca Falls, suffragist sheet music and cartoons, photographs, leaflets, and broadsheets.

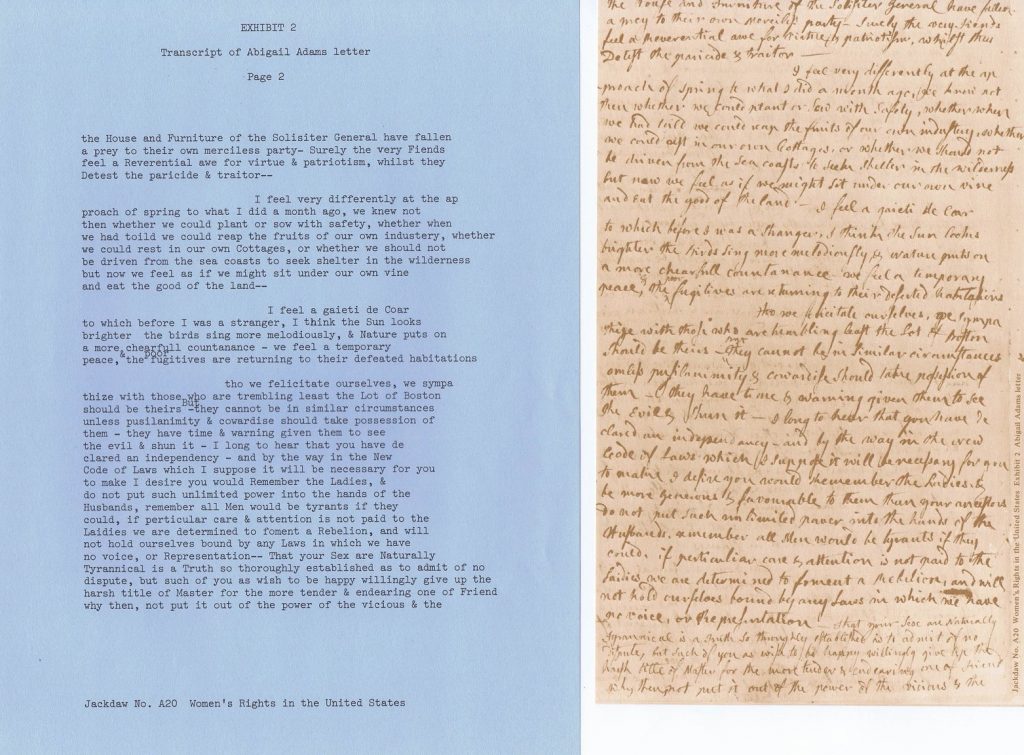

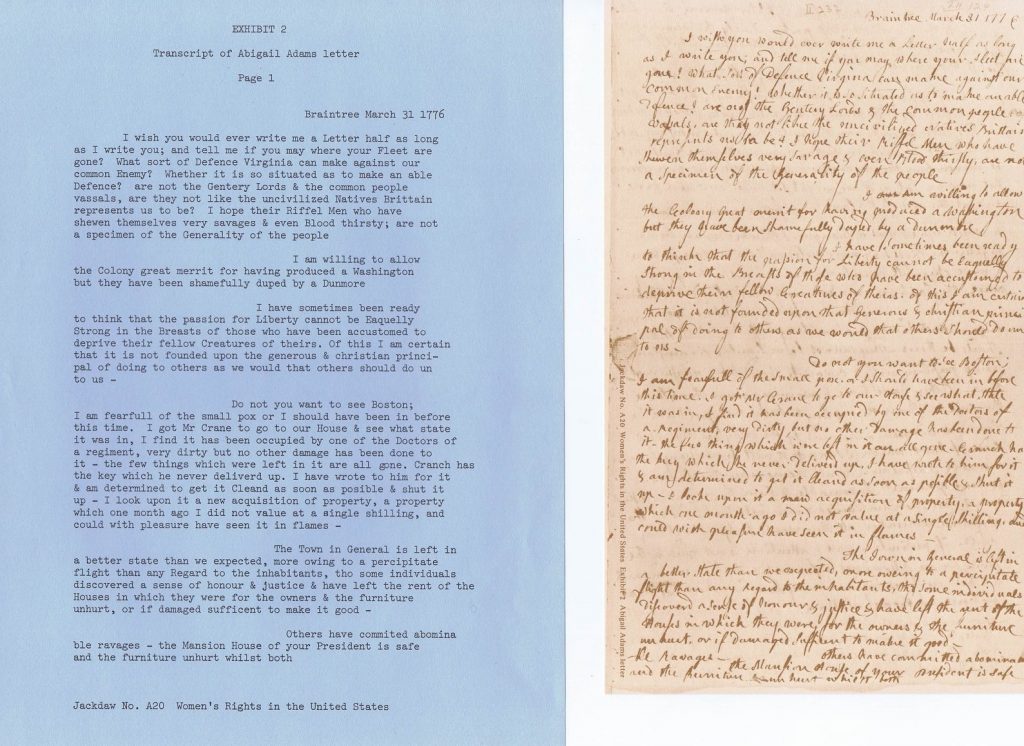

Our next excerpt from the 1974 issue of The Jackdaw, compiled by Mary Stetson Clarke, is a letter from Abigail Adams to her husband, John, dated March 31 and April 5, 1776, at which time John was in Philadelphia with the Continental Congress laboring towards the passage of the Declaration of Independence.

Abigail Adams, 1766, painted by Benjamin Blythe.

Abigail Adams, 1766, painted by Benjamin Blythe.

(Massachusetts Historical Society)

This is the famous letter in which Abigail urges her husband: “I desire you would remember the Ladies…” (page 2, paragraph 3)

“…all men would be tyrants if they could, if particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice, or representation…”

But the letter is worth reading in its entirety, which Clarke makes possible here both in the original and a typewritten transcript. Adams discusses a smallpox epidemic and her attempts to make saltpeter for the manufacture of gunpowder for the colonial troops.

In the second paragraph on the first page Adams writes: “I am willing to allow the colony great merit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore.”

She is referring to John Murray, the Fourth Earl of Dunmore and the Royal Governor of Virginia, who had issued a proclamation on November 14, 1775 in which he offered freedom to slaves who would leave their patriot masters and join the loyalist forces. Though relatively few slaves actually joined the British army as a result of this proclamation, it inspired 100,000 slaves to risk everything in an effort to be free.

Adams proceeds to chide the Founding Fathers: “I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Equally Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs.”

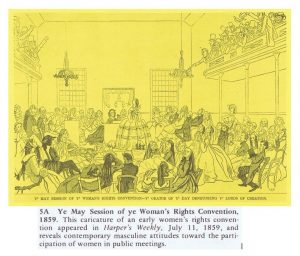

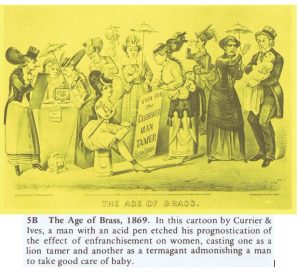

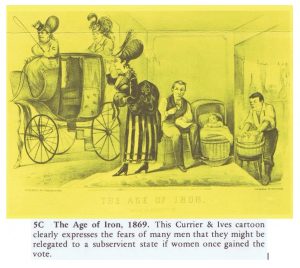

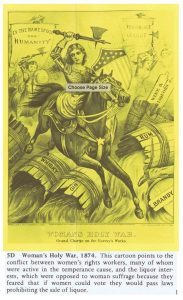

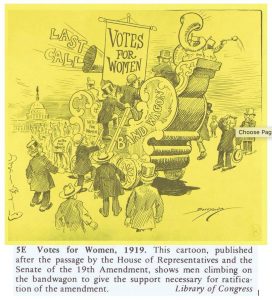

The following excerpt from the 1974 issue of The Jackdaw contains five political cartoons on women’s rights, from 1859, 1869, 1874, and 1919.

“During the entire period of the struggle for women’s enfranchisement, there was widespread publication of cartoons ridiculing the cause. The comic legend was one of the most effective weapons employed to combat the women’s rights movement. Suffragists who bravely withstood taunts and insults were occasionally defeated by scornful laughter.”

– Mary Stetson Clarke

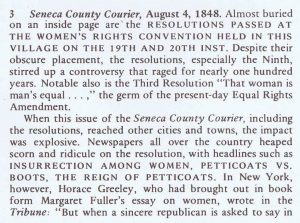

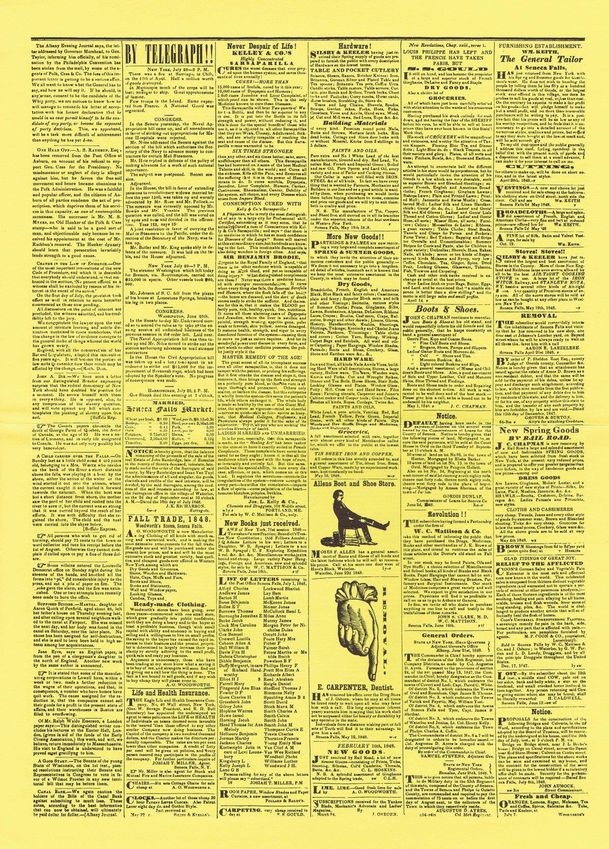

The following excerpts from the 1974 issue of The Jackdaw, take us to Seneca Falls, NY, for the Women’s Rights Convention of 1848. Arnold N. Barben comments on the pages from the Seneca Falls Courier.

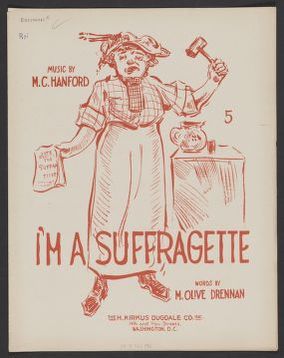

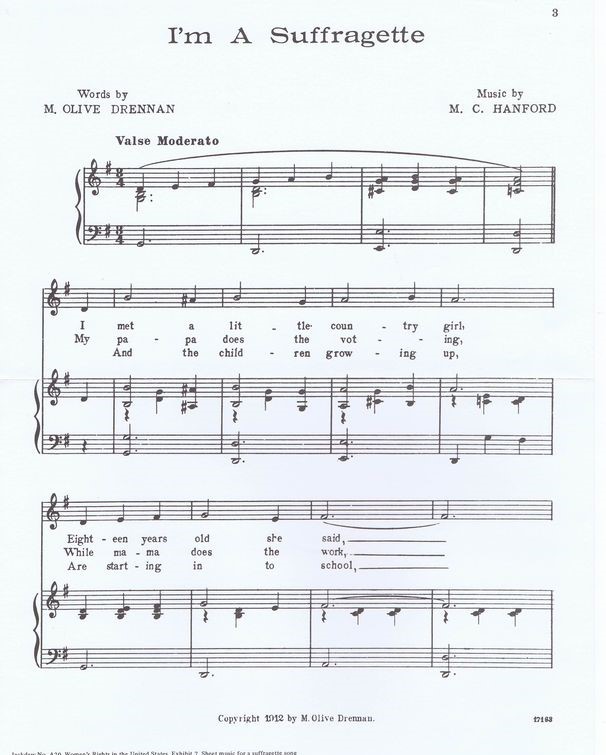

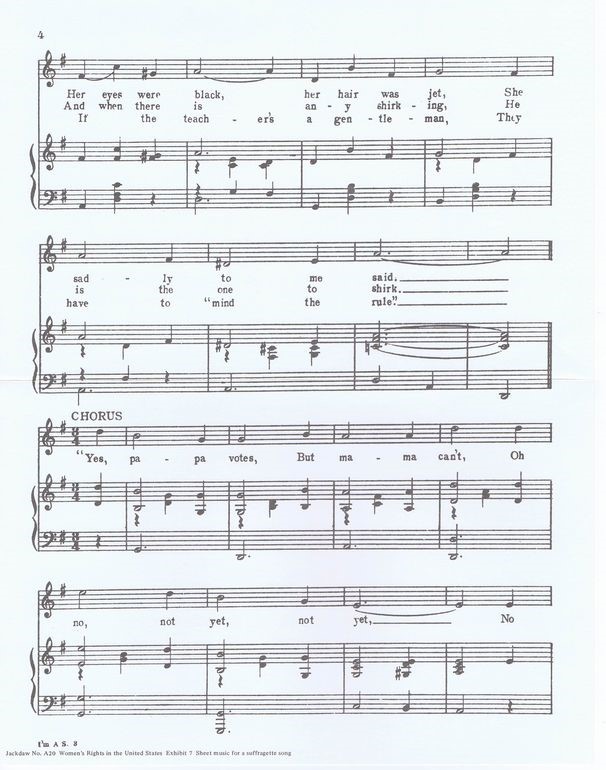

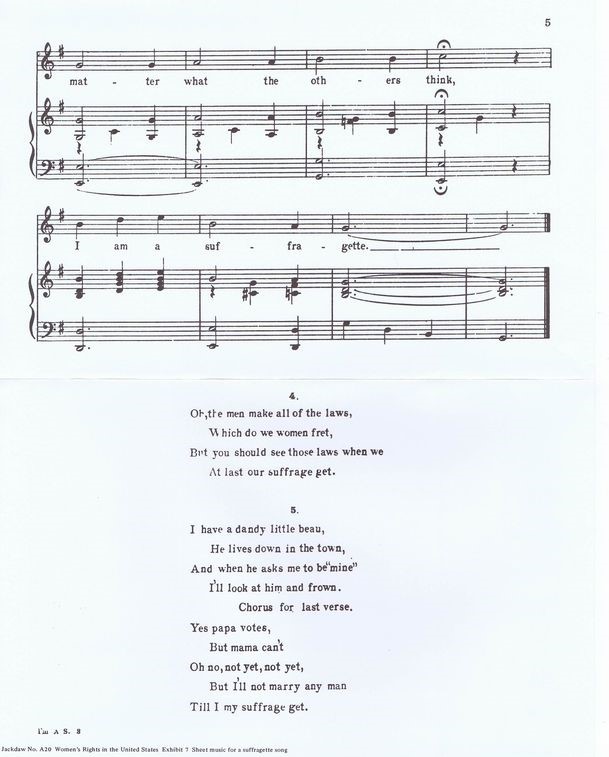

From The Jackdaw includes sheet music for “I am a Suffragette” (1912) music by M. C. Hanford and lyrics by M. Olive Drennan.

Want to sing along? Here’s a video of Jane Voss singing this song, accompanied by Hoyle Osborne on piano: I am a Suffragette video

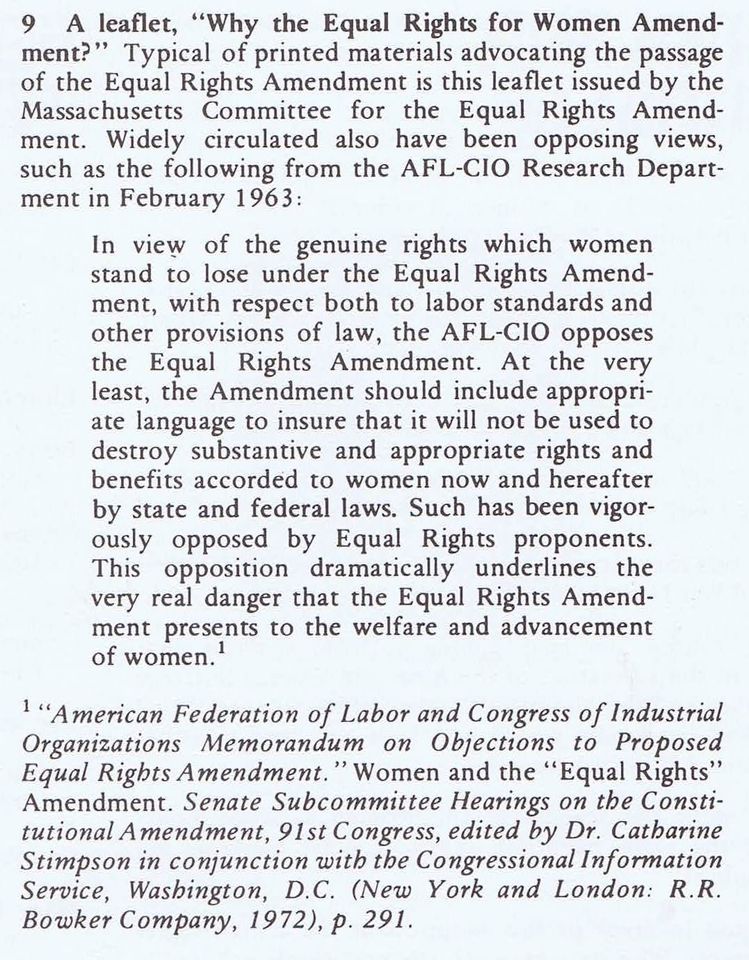

With 1974 fast retreating in the rear-view mirror of history, the contemporary exhibits that Mary Stetson Clarke included in The Jackdaw are now of historical interest to the young and nostalgic interest to those who lived through that era of second wave feminism in the United States.

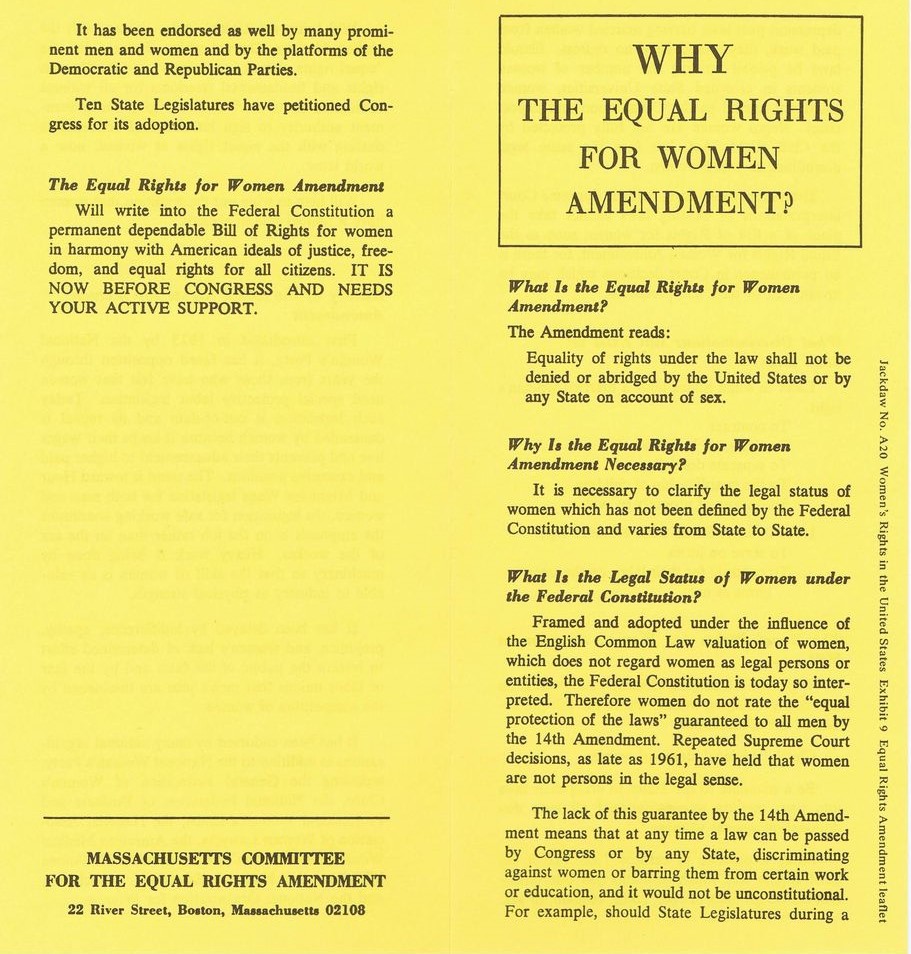

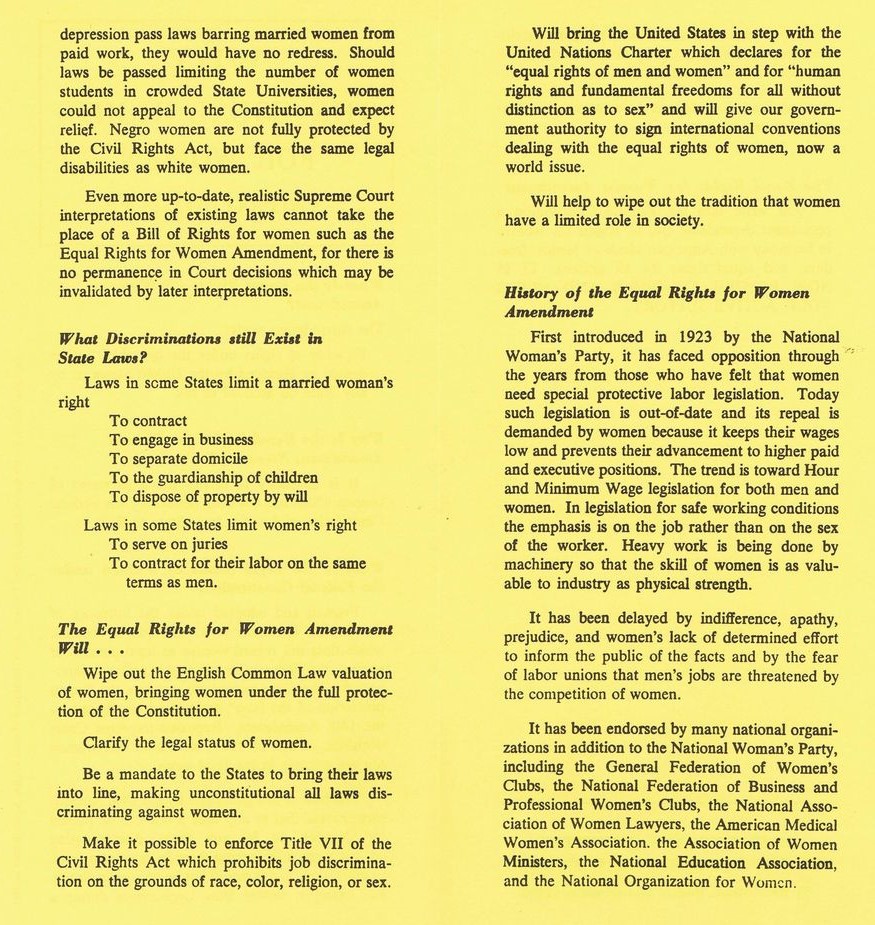

Here we have a leaflet supporting the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

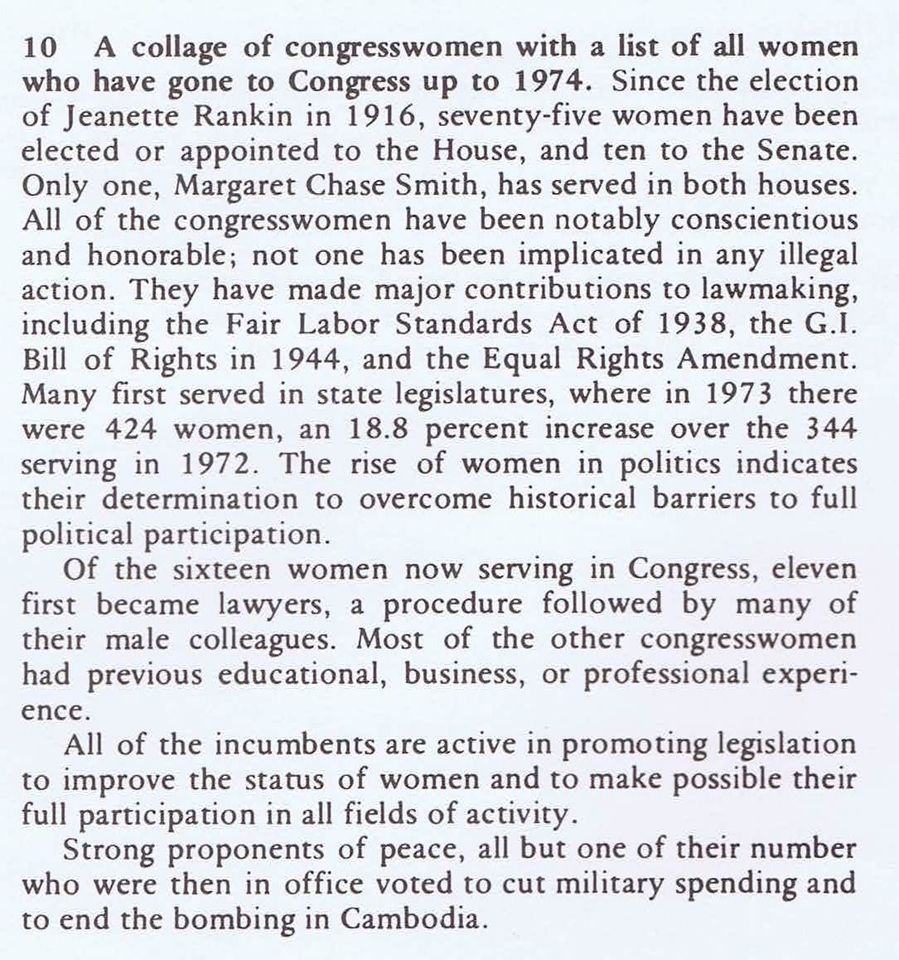

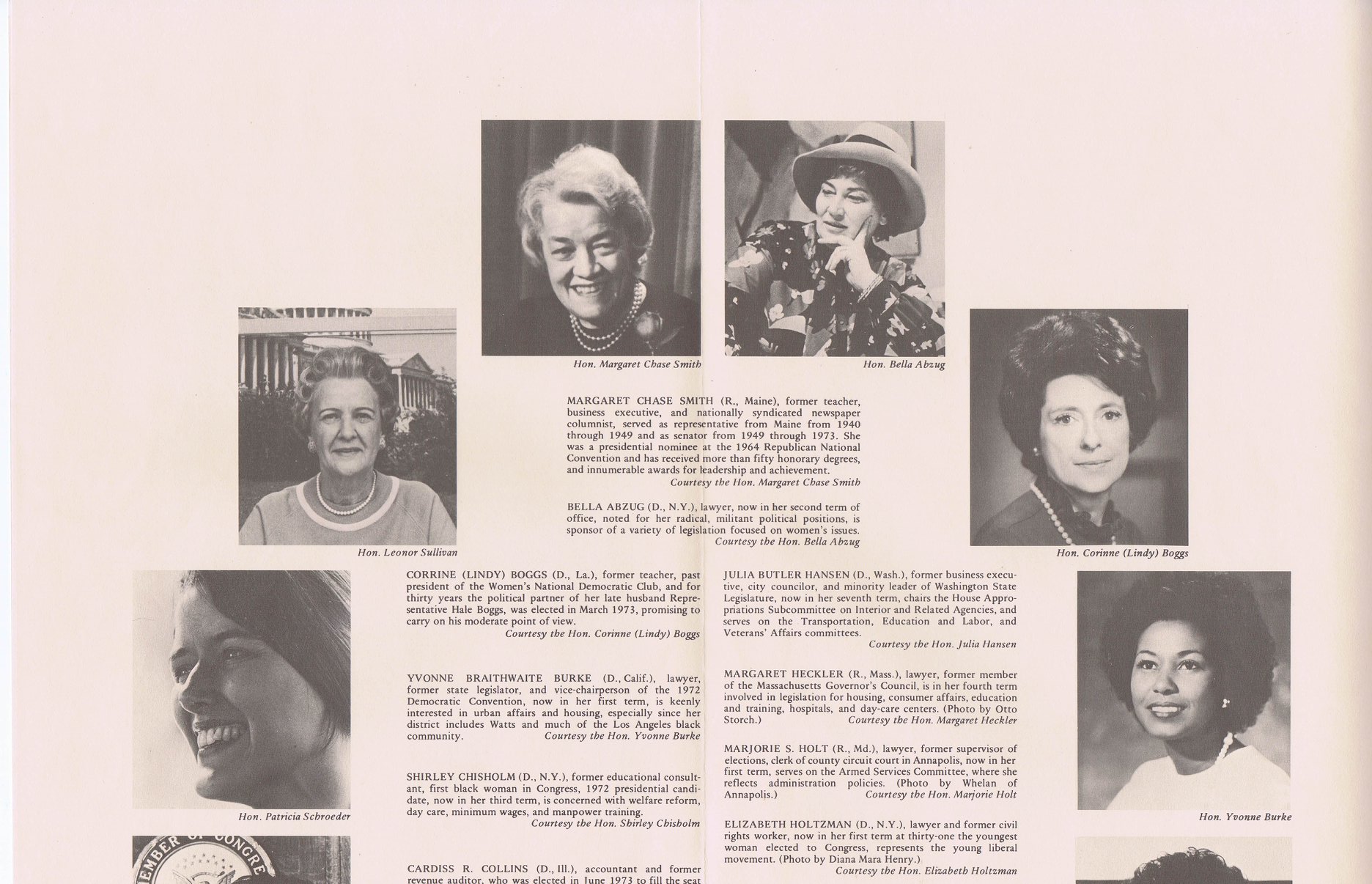

Here Clarke provides a collage of women who have served in Congress up to 1974. We apologize that some of the images and text were not scanned fully.

How many more could we add to that list today?

Happy Women’s Equality Day!

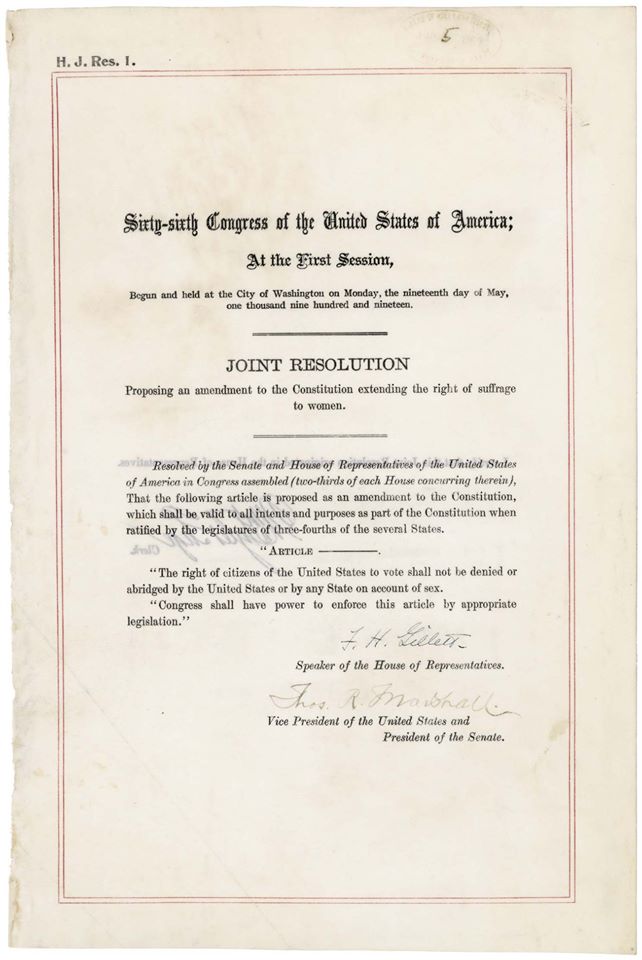

Women’s Equality Day is celebrated in the United States today, August 26th, 2020, to commemorate the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits the states and the federal government from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex.

Suffrage100MA commemorated the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment. Learn more by clicking here: Suffrage100MA.

If you have not seen the PBS series “The Vote” about woman suffrage, you can find it here: The Vote.

The National Archives Museum featured an online exhibit about Woman Suffrage. Click here to learn more: Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote

Women and Williams College

Fifty years ago, in 1970, Williams College opened as a coeducational institution. Women had studied at the college before, but none had been granted degrees. The women who entered in 1970 were full fledged undergraduate students at the college.

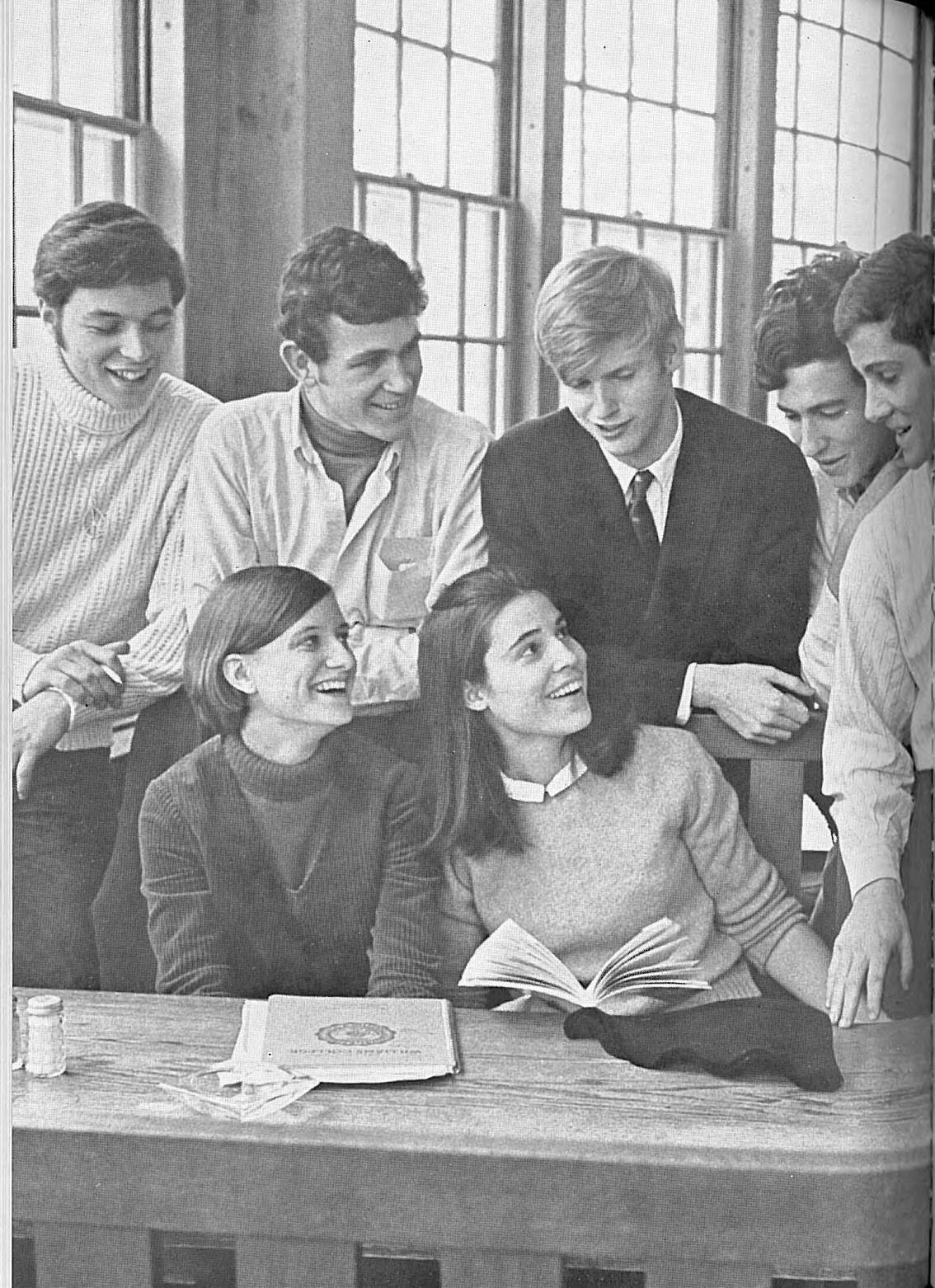

Quote and photo from the 1970 Gulielmensian

This had a BIG impact on the town because the College elected to increase its enrollment to accommodate female students, rather than slowly replace half of its current enrollment with women. So this week we will be looking at the impact of women at Williams on the town.

Click on this link to go to Sylvia Kennick Brown’s timeline of Williams’ road to co-education:

https://unbound.williams.edu/williamsarchives/islandora/object/exhibits%3A34

The decision to go co-ed came close on the heels of the dissolution of the fraternities. Up until 1962 the college did not house or feed the majority of its students, the fraternities did. And those fifteen Greek organizations combined formed the town’s third largest employer at that time – the first being the College itself and the second being Mount Hope Farm, which also closed in 1962, just as The Clark and the Williamstown Theatre Festival, both founded in 1955, were expanding, shifting the town’s economy from agriculture and education to education, tourism, and the arts.

So the 1960s were a decade of upheaval for the town as power, jobs, and land changed hands. The college needed to expand its facilities quickly to accommodate its women. Most of the fraternity and Mt. Hope properties came into the college’s hands, and the Williams Inn and its satellite properties, which had always been college-owned, were put to new uses. The Greylock Quad was built.

Photo by William Tague of Jennifer Dorr White, Williams 1981, at a 1979 celebration of coeducation at the College

Photo by William Tague of Jennifer Dorr White, Williams 1981, at a 1979 celebration of coeducation at the College

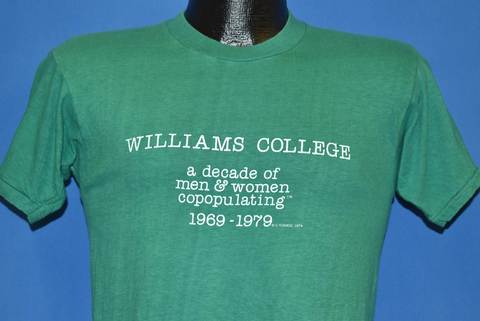

t-shirt made for 1981 celebration

t-shirt made for 1981 celebration

No matter how separate you see the town and the college, the rapid growth and physical expansion of the latter, and the cultural shift of moving from a single sex to a coeducational institution, had a big impact on the town.

More female faculty and staff were hired and became part of the Williamstown community.

Margaret Johnson Ware

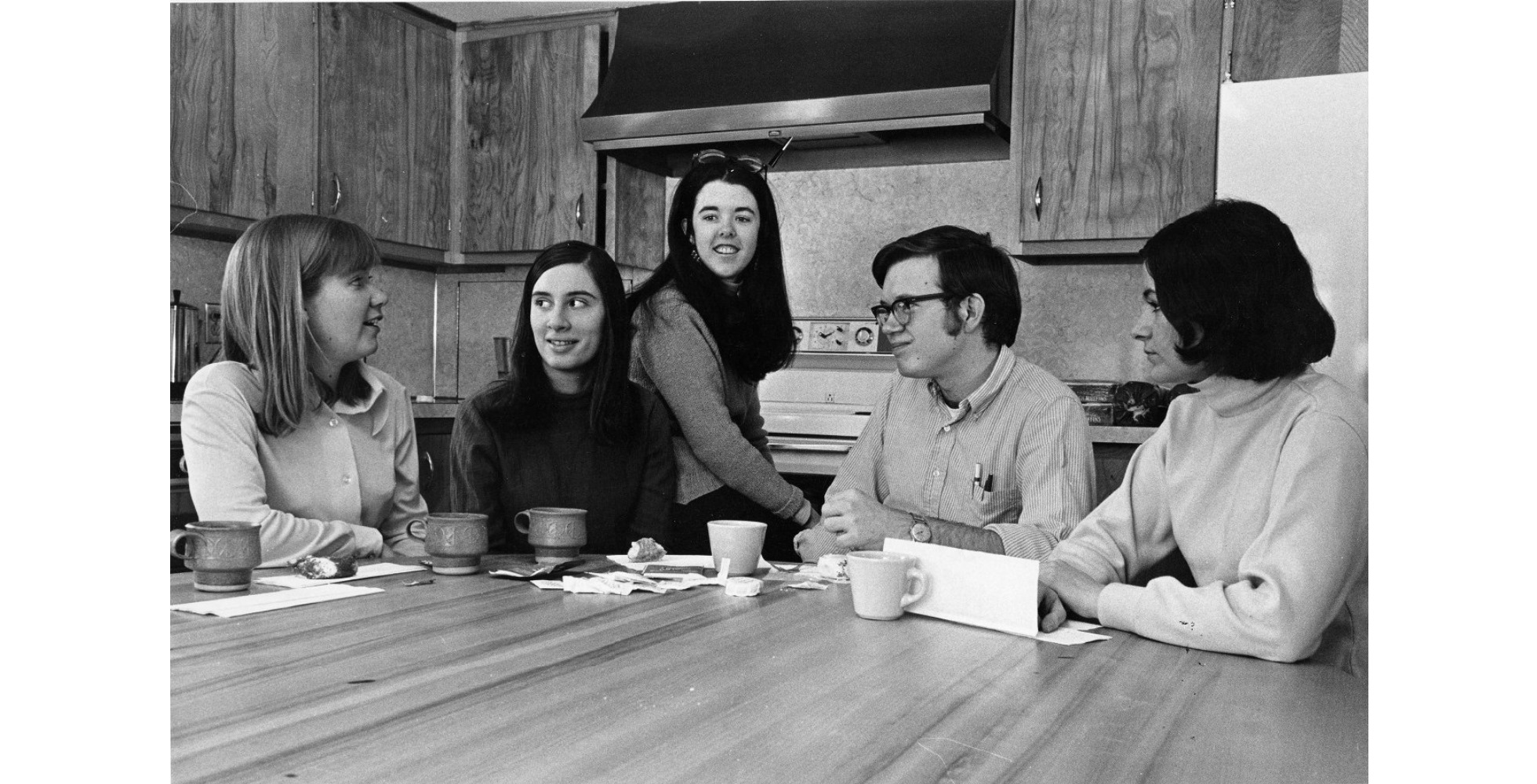

Margaret Johnson Ware came to Williams as an exchange student from Mt. Holyoke in the fall of 1969 and the spring of 1970. Here are excerpts from an interview with her about that experience:

“There were very few co-ed college choices for women in the late 1960’s A ten college exchange program had been started with five women’s colleges and five men’s. Williams had had 20-30 female exchange students from Vassar in the spring semester of 1969, and I was one of about 60 women on campus that fall. (Click this link to read the 1969 article by Thomas W. Bleezarde on the reception of those first female exchange students from Vassar.) https://williams1970.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/WomenWinter1969-c.pdf.

There were women from Wheaton, Vassar, and Mt. Holyoke in my dorm. We were an oddity. They really knew nothing about having women on campus. There was lots of sexism. They treated us all like we were at a girls prep school in 1947. We had different rules from the male students, for instance we had a curfew and they didn’t.

They put us all in Lambert House at the foot of Hoxsey Street and we were all squished in. There was no space for us to have desks in our rooms so we were asked to study in the hallways. I went to the administration and said, ‘No man at this college has been asked to study in a hallway and no woman should be either.’ After that they moved some people out to Lambert Annex and we had more breathing room.

Margaret Johnson, second from left, with other female exchange students and Williams student Robert Ware visit in the kitchen of Lambert House in 1970.

Margaret Johnson, second from left, with other female exchange students and Williams student Robert Ware visit in the kitchen of Lambert House in 1970.

Photo by William Tague.

I wrote in my application that I was a political science major and wanted to study with James MacGregor Burns, which I did. I took European history with Bob Waite, Shakespeare with Arthur Carr, and two semesters of music with Irwin Shainman.

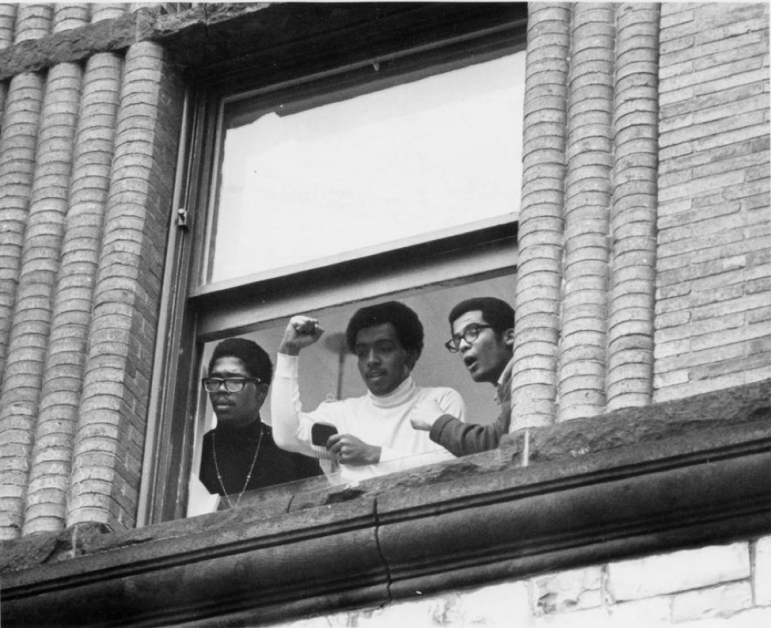

Most women were there looking for guys, I already had a boyfriend at Williams. I stayed for both the fall 1969 and spring 1970 semesters, and I lived in Williamstown the summer before and the summer after. It was an exciting time to be here because that was the year of the student strikes and when the African American students took over Hopkins Hall to protest the treatment of people of color at Williams.”

William Jefferson ’70, Preston Washington ’70, and Michael Douglass ’71 look out of the registrar’s office window during the Occupation of Hopkins Hall

William Jefferson ’70, Preston Washington ’70, and Michael Douglass ’71 look out of the registrar’s office window during the Occupation of Hopkins Hall

Students at Chapin Hall in 1970 listen to a student speaker during the protests that disrupted commencement 50 years ago.

Students at Chapin Hall in 1970 listen to a student speaker during the protests that disrupted commencement 50 years ago.

From the Williams College Archives and Special Collections.

Nancy McIntire

Nancy McIntire had never worked at a single sex institution until she came to Radcliffe in 1965 to serve as Director of Financial Aid. It was from that post that Williams College snagged her to be their first female dean as they went coeducational. Nancy talked to us about those early years.

Nancy McIntire. Portrait by Kevin Kennefick

Nancy McIntire. Portrait by Kevin Kennefick

“Things were chaotic on college campuses in the late 1960s and I was ready to make a move and get out of Cambridge. And I wanted to do less financial aid and more involved with admissions and student life. Williams offered me a job as dean with some admissions work as well. It was the right move.

Williams had been looking at the question of coeducation for several years before they hired me. They wanted to increase the size of the college and the question was to add more men or to go co-ed. They didn’t want to decrease the number of men to add women. None of the men’s colleges going co-ed at that time wanted to do that.

Berkshire Eagle article about Nancy’s hiring.

Berkshire Eagle article about Nancy’s hiring.

One of the reasons Williams chose coeducation was the theory that women would fill in ‘under-subscribed curriculum areas’ such as art and music. They quickly found that there was no big difference between the majors men and women chose.

The Committee chaired by Joseph Kershaw recommended that the College move quickly towards a 50/50 ratio. The first co-ed undergraduate class was about 30-35% female.

Microaggressions were commonplace in the early days of coeducation at Williams, but overall the College made a really smooth transition. The Board of Trustees was very supportive. The alumni are very loyal to college and they had just lived through the decision to disband the fraternities. Basically, all the pro-fraternity alumni had already departed so they weren’t around to bother me. And the remaining alumni were very quick to realize that now their daughters cold follow in their footsteps at Williams as well as their sons.

Click here to read the 2006 interview with McIntire in the Williams Alumni Magazine. https://www.williams.edu/files/McIntire_feat.pdf

There were aspects to having women on campus that the college hadn’t thought through, like bathrooms in Bronfman Science Center. I remember a female faculty member ‘liberated’ a bathroom there!

At the start men had control over all the social money and there were many activities the women just weren’t enjoying like the activities in the houses. Mark Taylor got the women some social money at Spencer House, but that was another reason to hurry towards equal numbers of male and female students. Social life would be better if the ratio was closer to 50/50.

Throughout the 1970s there were incidences of bad behavior. Occasional outbursts from men in student housing, signs that said ‘Coeds Go Home’ Once some students took an inflatable doll to Sawyer Library, put pants on her, doused her in red juice, and tossed her into a reading room.

The college had not made aggressive moves towards hiring female faculty. None of the female faculty they hired at the time they went co-ed made it through. It took more than a couple of hiring seasons to get women into the tenure pipeline. It really took longer than it should have.

Bob Peck wanted to wait for female students to ask for athletics rather than setting up programs for them. So women’s sports could have been developed more quickly.”

Nancy arrived at Williams in 1970 and worked as assistant and then associate dean. Then in 1983 she became the assistant to the president which shifted her from working with students to working with the faculty. She retired from that position in 2006, after 36 years at Williams, but she remains an active and beloved member of our Williamstown community.

Photo Geoff Foster, Concord Monitor.

Cover of Williams Alumni Magazine, Summer 2015.

Cover of Williams Alumni Magazine, Summer 2015.Illustration by Peter Strain.

Because this exhibit is limited in its scope, visitors are encouraged to seek more information about the woman suffrage movement, the challenges women, and particularly women of color, faced in the effort to secure the right to vote. On August 20, 2020, The New York Times published a broad overview of woman suffrage. NY Times Woman Suffrage Online Resources

Additionally, the July 1, 2019 New Yorker featured an article that provides helpful information. “The Imperfect, Unfinished Work of Women’s Suffrage,” by Casey Cep

Smithsonian Magazine’s article from April 9, 2019 tells more of the story of woman suffrage. “How Women Got the Vote is a Far More Complex Story Than the History Textbooks Reveal,” by Alicia Ault

Do you have women in your family whose stories should be told and preserved at the Williamstown Historical Museum? We would like to collect and share the stories of all of Williamstown’s residents. Email Sarah at [email protected] to tell us your story.

Daniel and Lucy Anthony

Daniel and Lucy Anthony Quaker Meetinghouse in Adams

Quaker Meetinghouse in Adams

Quaker Meetinghouse interior

Quaker Meetinghouse interior