This week’s historical marker is much harder to locate than some of the others. Do you know where the First Meeting House was located in Williamstown and its importance in our town’s history?

There was no separation of church and state in the late 1700s, and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts decided that in order to incorporate as a town a community had to have a meetinghouse and a “learned and settled pastor.” This meant what we now call a Congregational minister. There was no choice, that was the religion of the Commonwealth.

The town needed to incorporate under the name of Williamstown in order to access the money left to them in Ephraim Williams’ will to establish a free school, and they needed a church and pastor in order to incorporate. And yet it took a decade those conditions to be met.

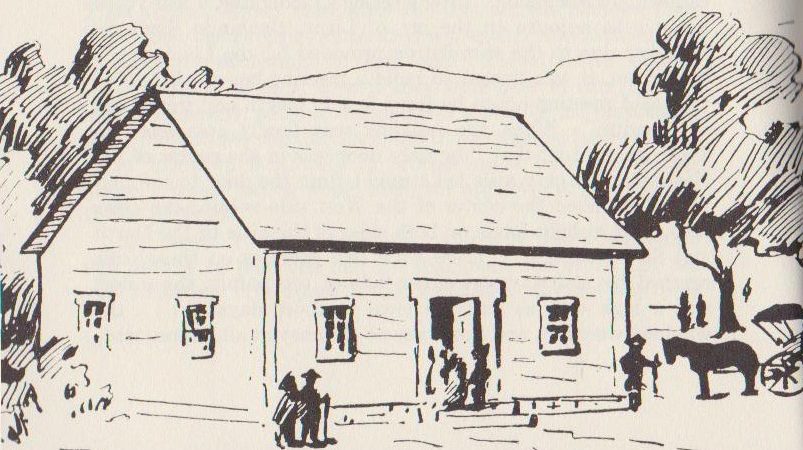

“In 1765 the town was regularly incorporated by the Province authorities at Boston…The proprietors and not the townsmen called and settled the first minister, Rev. Whitman Welch…and paid all the expenses of his ordination; they built and paid for the first framed meetinghouse in 1768…” – Arthur Latham Perry “Williamstown and Williams College” 1899

Moira O’Hara Jones gave a great talk for us in 2015 about the relationship between the town and what is now the First Congregational Church, on the occasion of that institution’s 250th anniversary.

First Church and Williamstown: 250 Years Together Video

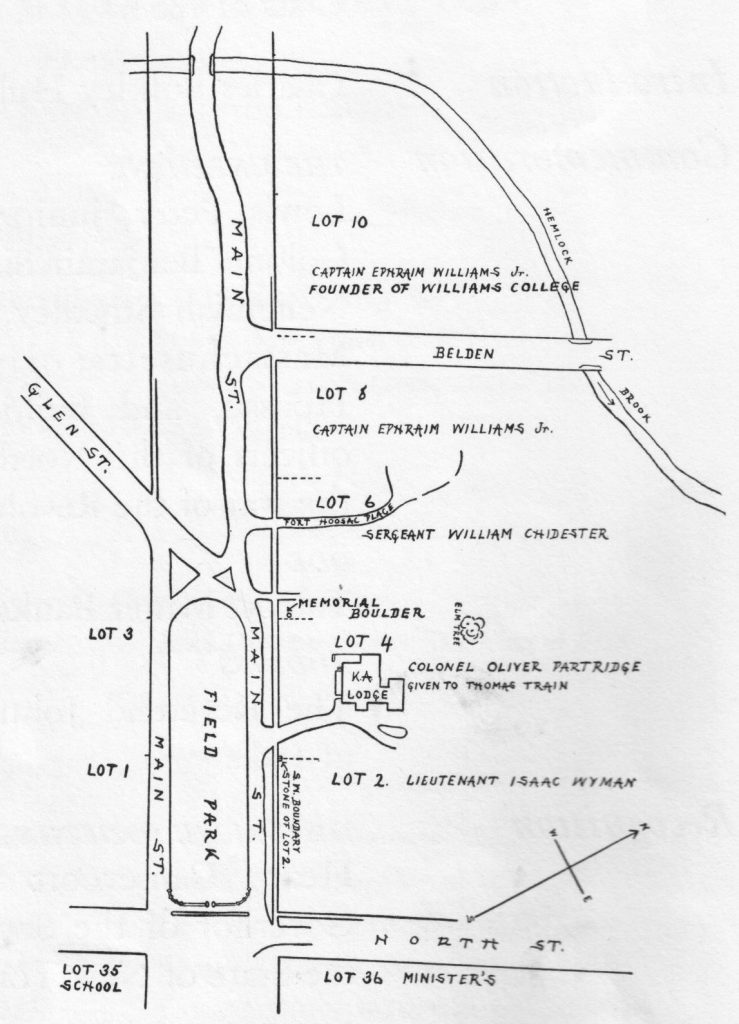

During the years between the settling of West Hoosuck and the construction of the first meeting house which enabled us to incorporate as Williamstown, there was a log cabin referred to as “The Schoolhouse” built around 1763 and located on Lot 36, which can been seen at the bottom right hand corner of this map, where it says “minister’s,” as indeed that lot had been originally reserved for the first minister. (The building would have been about where Mark Hopkins Hall is on the current Greylock Quad.)

Despite its name, it was never used as a school, but as Arthur Latham Perry wrote in “Origins in Williamstown” (1894): “…the proprietors uniformly held their meetings at this schoolhouse for several years; and public worship was held in it, whenever there was any, until the first rude meeting-house was built, 30’ x 40’, in 1768.”

Even after the first meeting house was built, Perry continues: “The log building acquired a certain sort of sanctity thereby, which was never wholly lost as long as it remained standing.”

As was evidenced on the afternoon of August 16, 1777, when the pious women of Williamstown gathered in the Schoolhouse “to pray for the safety and victory of their fathers and brothers and kinsfolk in the battle of Bennington, then raging.”

The Schoolhouse was probably taken down in the mid-19th century when the original “Mansion House” hotel was erected at the front of that building site.

“The proprietors and not the townsmen called and settled the first minister, Rev. Whitman Welch, in 1765, and paid all the expenses of his ordination; they built and paid for the first framed meetinghouse in 1768…” – Arthur Latham Perry “Williamstown and Williams College” 1899

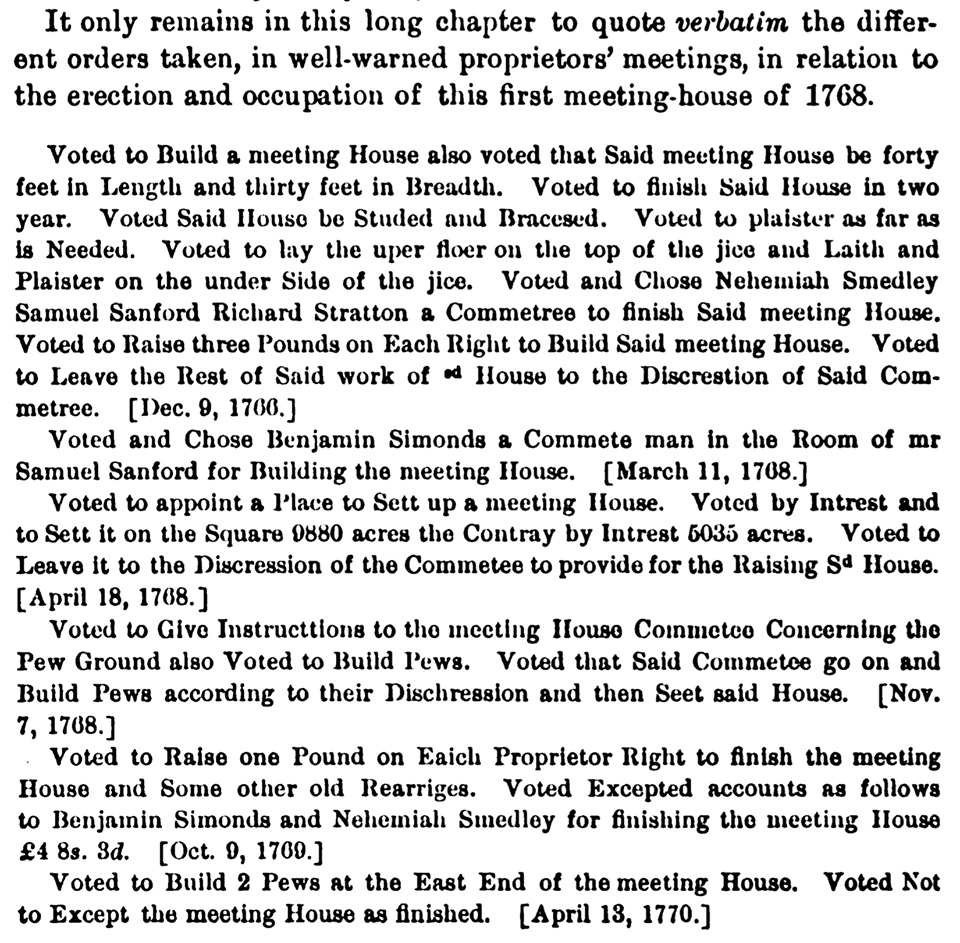

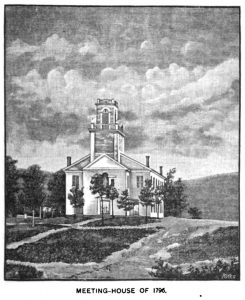

The accompanying excerpt from Perry’s “Origins in Williamstown,” 1894, features snippets from Proprietors’ Meeting minutes c 1766-1770 pertaining to the building of the first meeting house, located in the middle of what is now Field Park. This drawing is the only representation we have of the first meeting house since it was replaced by the second meeting house before the invention of photography.

The first meeting-house was 30′ x 40′. At first it would have had rough bench seating, but then pews, probably box pews, as the First Congregational Church has today, were built and “seated.”

“Colonial churches were generally ‘seated’ each year; that is, each worshipper was assigned a particular seat, determined in accordance with their social or perceived spiritual status in the community.” – John Ogsapian, “Church Music in America, 1620-2000” 2007

There was a “seating committee” for the first meeting house in Williamstown, but not for the second.

While there was talk of “having the gospel preached in this town” as early as the second Proprietors’ Meeting in April 1754, no concrete action was taken until the Proprietors’ Meeting of March 10, 1763, after the French and Indian War had ended, when it was voted “that for the future” they “would have preaching,” and accordingly a call was given to Rev. Moses Warren to preach on probation.

Whitman Welch, the sixth child and youngest son of Thomas and Sarah (Whitman) Welch, was born on June 5 1738 in Milford, CT. He was orphaned by the age of ten when he went to live with an uncle in New Milford, CT, and where in time he was married to Ruth Gaylord.

Welch studied theology, graduated from Yale in 1762 and was licensed to preach by the New Haven Association of Ministers on September 25, 1764.

Immediately after the incorporation of Williamstown, the Proprietors called Welch “to the work of the ministry in this town” on July 26, 1765. He was ordained in October or November of that year, “at which time a church was gathered,” although the first meeting house wasn’t finished until 1768.

While Welch was given the use of Lot 36, the “Minister’s Lot,” on what is now the northeast corner of Main and North Streets (the northern junction of Rts. 2 & 7), he promptly sold it to Josiah Horsford for £25 and bought 18 acres of farmland on the Green River, where he made his home next door to Nehemiah Smedley.

When the Revolutionary War began in 1775, Welch sold his farm to Smedley and joined the militia as a chaplain. He died of small-pox near Quebec on April 8, 1776, at the age of 38. His widow and children had returned to New Milford when he joined the war effort and never returned to Williamstown.

This map shows Williamstown in the upper left hand corner, and New Milford, CT in the lower left, on the Housatonic River just north of Danbury. A number of families followed Whitman Welch north when he was called to preach in Williamstown.

Williamstown struggled to attract a “learned and settled pastor.” According to Arthur Latham Perry: “They had had hard luck and had been at much expense even to get a suitable man to try for a settlement. In two cases where the candidate was willing, the constituency disapproved of him.”

But in neighboring Adams and Cheshire, founded by Quakers and Baptists respectively, they couldn’t incorporate as towns because the Commonwealth of Massachusetts didn’t recognize their worship or clergy as “Christian.”

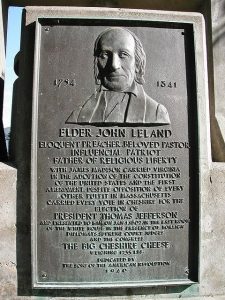

In Cheshire Baptist pastor John Leland worked hard to get Thomas Jefferson elected President in 1800, because he believed Jefferson would work towards a separation of church and state in the newly formed USA, allowing towns like Adams and Cheshire to incorporate without having to abandon their preferred form of worship.

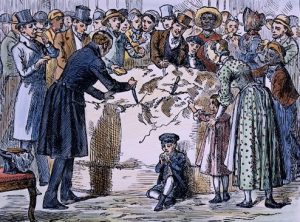

Once Jefferson was in the White House, Leland concocted an audacious PR stunt to call the President’s attention to his cause. He asked all the dairy farmers in Cheshire to donate a quart of milk, retrofitted a big cider press, and created what became known as the Mammoth Cheese.

The cheese weighed 1,235 pounds, was 4 feet wide, and 15 inches thick. Leland accompanied the cheese all along the three-week, 500-mile route. preaching fervently all the way. The cheese bore the Jeffersonian motto “Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.”

In keeping with the Quaker’s abolitionist beliefs, Leland informed Jefferson that the Cheese was made “without the assistance of a single slave.”

Leland arrived on January 1, 1802, and presented the cheese to Jefferson, who that very afternoon, penned a letter to the Baptist community in Connecticut in which he coined the phrase “separation of church and state.”

So the people of northern Berkshire County played an important role in freeing both the states and the various faith communities from being under each other’s control.

You can visit the Cheshire Cheese Monument – a replica of the cider press used to create the cheese – across from the Cheshire post office on the northeast corner of Church and School Streets.

Have you spotted the historical marker honoring our first meeting house yet? Both the first and second meeting houses were built on that location, above the initial settlement , on what was then called “The Square,” now the east end of Field Park, formed by the intersection of Main Street with South and North Streets.

The construction of the first meeting house predated the establishment, or even the idea, of a college in town. The future of what we now call the Congregational Church in Williamstown was dictated by the needs of the college, not the congregation.

The first Commencement at Williams College was held on September 2, 1795, in the first meeting-house and “it was felt that the place was unsuitable.” President Fitch immediately began soliciting donors to help erect a temporary gathering place for major college events, but nothing came of that effort.

Before the next Commencement in 1796 there was a stronger and more varied opposition to going into the old meeting-house. Thomas Robbins (1777-1856, Yale & Williams 1796), who was to speak, wrote in his journal : “A scandal to have Commencement in such an old meeting-house.”

According to Arthur Latham Perry: “The College Trustees voted, ‘to hold the next Commencement in the town of Pittsfield or Lanesboro unless a suitable place should be provided in Williamstown,’ and appointed a committee to carry their vote into effect. But nothing was then accomplished, doubtless owing to much ill-feeling then prevalent as between town and college on political and other grounds, and the Commencement of 1797 also was held in the small and dark building.”

But on July 15 of that year Robbins wrote: “Great disturbance in town on account of the meeting-house being set on fire last night: it was happily extinguished: various conjectures about the perpetrators.”

The remains of the first meeting house were “removed a short distance” and used as a schoolhouse, and the second meeting house was erected on the site.

Perry wrote: “[The second meeting house] was so far advanced toward completion at the time of the Commencement of 1798, that its exercises were held within it, and thereafter uniformly until its destruction by fire in 1866.”