Another Outstanding Woman of Williamstown

Margaret Lindley

Margaret Lindley

1900-1966

Although born in North Adams, Margaret Jones was educated in the Williamstown public schools, the place where she would build her career as an adult.

She graduated from the North Adams Normal School (now MCLA) and married Laurence Lindley, a self-employed carpenter, before starting her teaching career in Williamstown at the Broad Brook School in 1919, She then taught at the Mitchell School until her retirement in 1960, serving two years as principal.

At the time of her retirement she was voted “Teacher of the Year” by the Grant-Mitchell PTA at a dinner celebrating her 41 year career, held at the 1896 House. John Bennett Perry (WHS class of 1959, son of Alton L. Perry and father of “Friends” star Matthew Perry) led a chorus of “Peg of My Heart” and sang two solos.

Even in retirement, Margaret Lindley couldn’t stay out of the classroom, serving as a substitute teacher at Mt. Greylock Regional High School.

She was a member of the Sigma Chapter of Delta Kappa Gamma, an honorary teachers sorority, and a member of the Mountain Chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star.

St. John’s Episcopal Church was packed for her memorial service in 1966 with teachers and retired teachers from the Williamstown Elementary School and Mt. Greylock, the Selectmen and Town Manager, businessmen, and friends in attendance.

The following year the town purchased 13.5 acres at the southern junction of Routes 7 & 2 from Michael Nicholas, owner of the Taconic Park Restaurant for use as a “municipal swimming pool and picnic area” to be known as Margaret Lindley Park.

Taconic Park (Abe’s Swimming Pool), c. 1960

Taconic Park (Abe’s Swimming Pool), c. 1960

Margaret Lindley Park

Margaret Lindley Park

Abolition and Woman Suffrage Stars – Angelina and Sarah Grimké

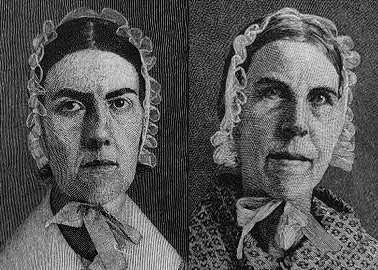

Ruth Bader Ginsburg famously said, “I ask for no favor for my sex. All I ask of our brethren is that they take their feet off our necks,” but she is not the originator of this phrase. That was Sarah Moore Grimké (1792-1873) who, along with her sister Angelina Emily Grimké Weld (1805-1879), was a leading voice in abolitionist and suffragist circles.

Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah Grimké

Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah Grimké

In 1836 Angelia published the abolitionist tract “An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South,” followed by Sarah’s “A Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern States.” In their native state their books were burned and their mother was informed that her daughters would be arrested if they dared to return home.

The following year Angelina and Sarah traveled around New England speaking on the abolitionist circuit, at first addressing women only in large parlors and small churches. Their speeches concerning abolition and women’s rights reached thousands.

Early in 1838 Angelina became the first woman in U. S. history to address a legislative committee when she was invited to speak to the Massachusetts Legislature in the Boston State House.

In 1838, Angelina married Theodore Weld, a leading abolitionist who had been a severe critic of their inclusion of women’s rights into the abolition movement.

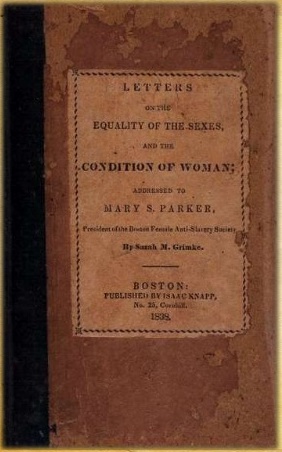

The same year Angelina married, Sarah’s letters to Mary S. Parker, President of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, were published as “Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Woman”. Later in the 19th century, these writings influenced suffrage workers such as Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott.

A PDF version of the “Letters…” is available here: https://tinyurl.com/y3bwe5c3.

A PDF version of the “Letters…” is available here: https://tinyurl.com/y3bwe5c3.

After Angelina’s marriage the Welds, their three children, and Sarah Grimké lived in New Jersey where they earned a living by running two schools. After the Civil War ended, the household moved to Hyde Park, Massachusetts, where they spent their final years. Angelina and Sarah were active in the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association.

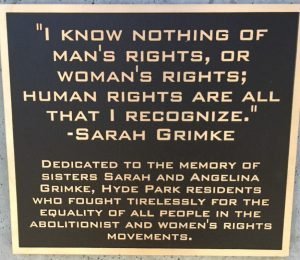

In 1870 the sisters marched with a group of 42 women through a snow storm and a crowd of angry men to cast their votes in the general election in Lexington, MA. They weren’t arrested because of the advanced ages (65 & 77) and their votes weren’t counted, but the Grimké sisters were the the first women to vote in Massachusetts.

Dedicatory plaque on the Grimké Sisters Bridge over the Neponset River in Hyde Park, MA.

Dedicatory plaque on the Grimké Sisters Bridge over the Neponset River in Hyde Park, MA.

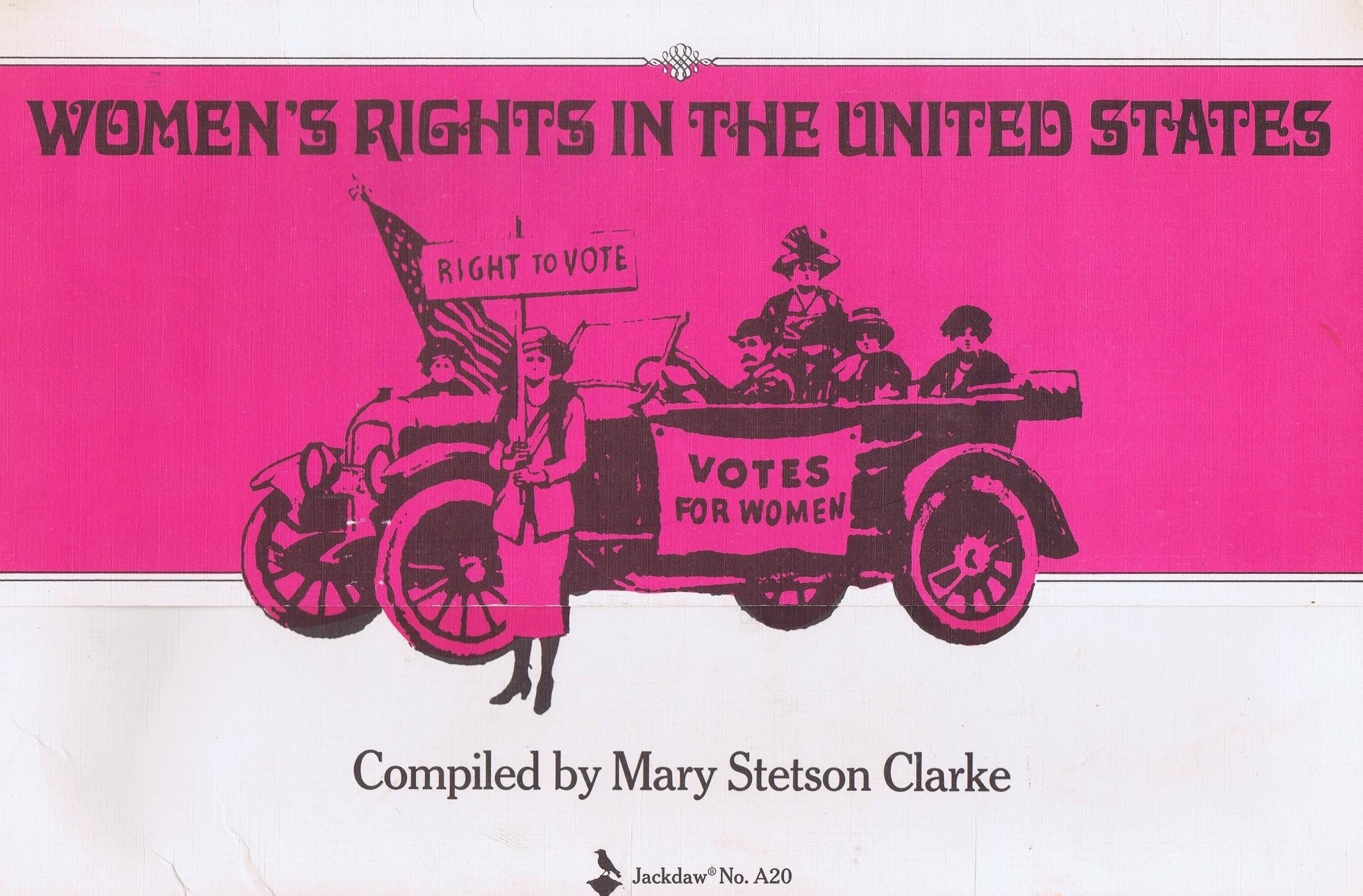

Mary Stetson Clarke’s Informative Review of “Women’s Rights in the United States”

Our friend, neighbor, and former WHM board member, Susan Stetson Clarke, has kindly shared with us the 1974 issue of The Jackdaw, focusing on women’s rights and penned by her mother, Mary Stetson Clarke (1911-1994).

“My mother was good at everything she did,” Susan Clarke recalled. “She was a wonderful housewife, a seamstress, a knitter, and then, when we were older, a writer and historian.”

Before we delve into the publication, let’s take today to get better acquainted with Mrs. Clarke.

Mary Stetson Clarke, 1911-1994.

Mary Stetson Clarke, 1911-1994.

Mary Stetson Clarke was born and brought up in Melrose, MA, where she was active in community affairs, a former member of the Conservation Commission, and a trustee of the Melrose Public Library, and on the board of the Melrose Historical Society. Other memberships included the American Association of University Women, New England Historic Genealogical Society, the Middlesex Canal Association, Massachusetts Library Trustees Association, and the Stetson Kindred of America.

She graduated from Boston University College of Liberal Arts, B.A. 1933, and was elected to its Collegium of Distinguished Alumni in 1976. She dd graduate study at Columbia University 1937-38.

After graduation from college she worked for four years on the staff of a Boston newspaper. She was married in 1937 to Edwin L. Clarke, an electrical engineer, who retired from MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory where he worked on research projects.

Following marriage and the birth of three children she wrote feature articles for various newspapers and magazines. When her children were in their teens she began writing historical novels. Later she wrote historical nonfiction, for children and for adults. She taught creative writing at the Boston Center for Adult Education, 1958-60; and was a research secretary at Harvard University, 1960-64.

Mrs. Clarke was the author of twelve books of historical fiction and nonfiction: Petticoat Rebels, The Iron Peacock, Pioneer Iron Works, The Limner’s Daughter, The Glass Phoenix, Piper to the Clan, Bloomers and Ballots, Immigration in Colonial Times, Women’s Rights in the United States, The Old Middlesex Canal, A Visit to the Iron Works, Iron in Colonial Times. Several received favorable reviews in the New York Times, The Glass Phoenix was a Junior Literary Guild book. Pioneer Iron Works was reprinted by the National Park Service which used the book as a text for its guides.

The Old Middlesex Canal is considered the definitive work on the subject.

“On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the publication of her book on the Middlesex Canal I went and spoke about my mother and her work, wearing an outfit that she had made me,” Susan Clarke recounted with pleasure.

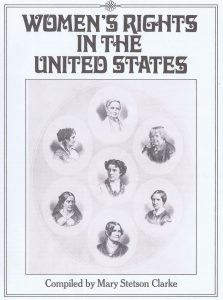

Let’s delve into our 1974 edition of The Jackdaw, compiled by Mary Stetson Clarke.

The opening pages contain some interesting images and postage stamps celebrating early suffragists: Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, Carrie Chapman Catt, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Livermore, Grace Greenwood (aka Sara J. C. Lippincott), Anna E. Dickinson, and Lydia M. F. Child.

The introduction and table of contents set the tone for the 50 anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment, and whets our appetites for what is to come – letters from Abigail Adams and Susan B. Anthony, news from Seneca Falls, suffragist sheet music and cartoons, photographs, leaflets, and broadsheets.

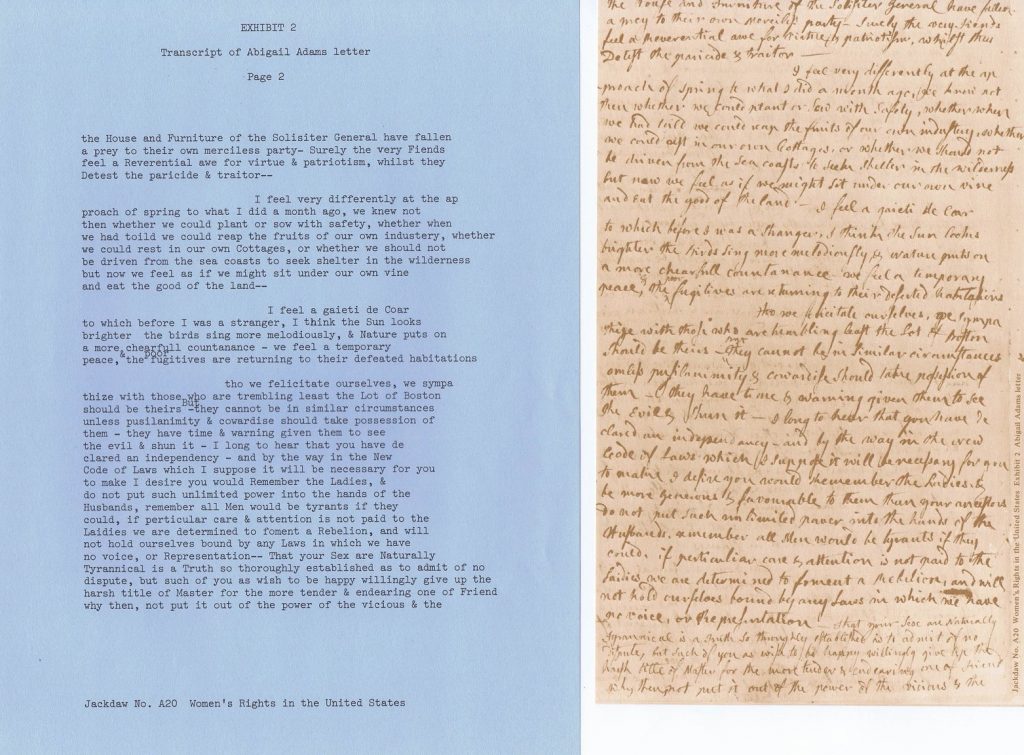

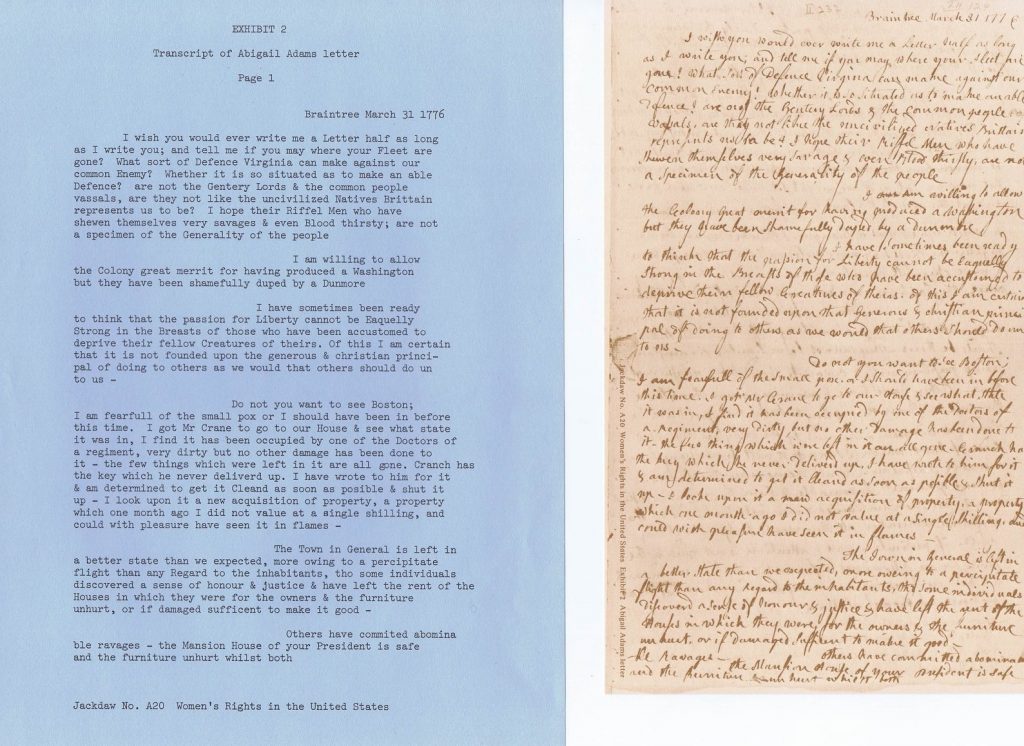

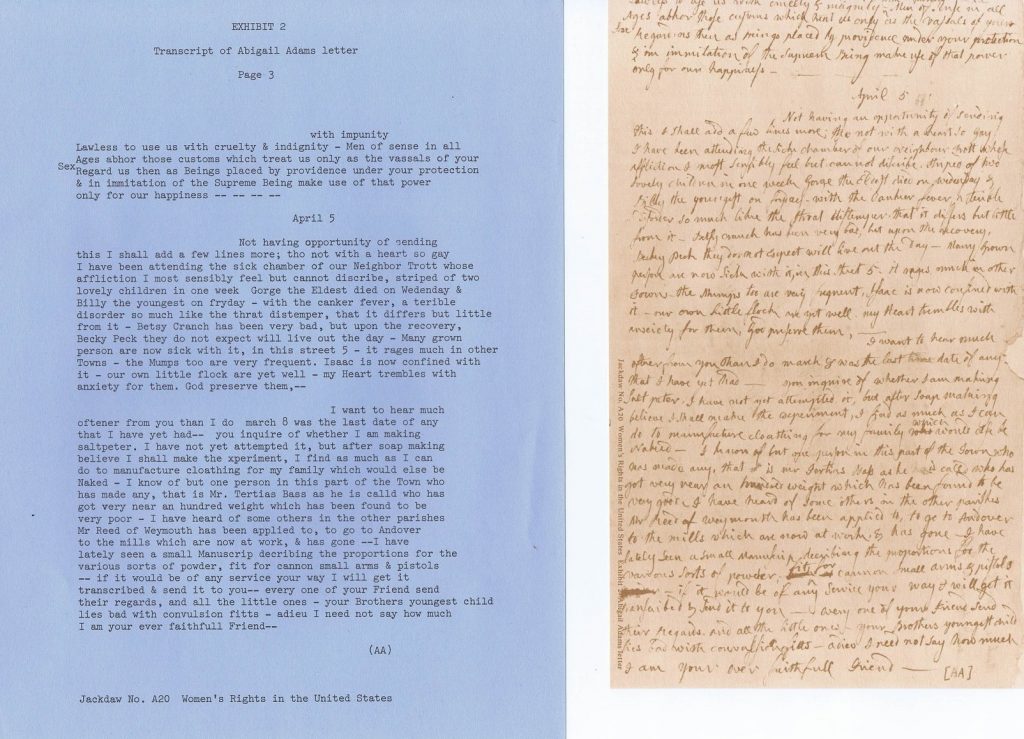

Our next excerpt from the 1974 issue of The Jackdaw, compiled by Mary Stetson Clarke, is a letter from Abigail Adams to her husband, John, dated March 31 and April 5, 1776, at which time John was in Philadelphia with the Continental Congress laboring towards the passage of the Declaration of Independence.

Abigail Adams, 1766, painted by Benjamin Blythe.

Abigail Adams, 1766, painted by Benjamin Blythe.

(Massachusetts Historical Society)

This is the famous letter in which Abigail urges her husband: “I desire you would remember the Ladies…” (page 2, paragraph 3)

“…all men would be tyrants if they could, if particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice, or representation…”

But the letter is worth reading in its entirety, which Clarke makes possible here both in the original and a typewritten transcript. Adams discusses a smallpox epidemic and her attempts to make saltpeter for the manufacture of gunpowder for the colonial troops.

In the second paragraph on the first page Adams writes: “I am willing to allow the colony great merit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore.”

She is referring to John Murray, the Fourth Earl of Dunmore and the Royal Governor of Virginia, who had issued a proclamation on November 14, 1775 in which he offered freedom to slaves who would leave their patriot masters and join the loyalist forces. Though relatively few slaves actually joined the British army as a result of this proclamation, it inspired 100,000 slaves to risk everything in an effort to be free.

Adams proceeds to chide the Founding Fathers: “I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Equally Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs.”

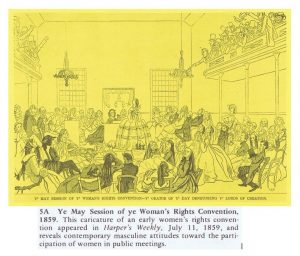

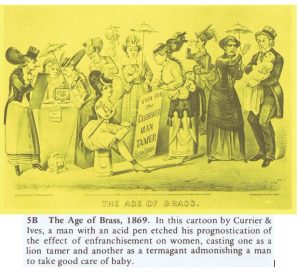

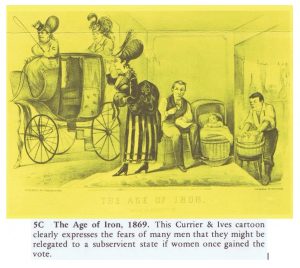

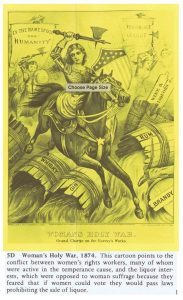

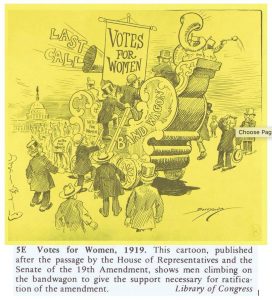

The following excerpt from the 1974 issue of The Jackdaw contains five political cartoons on women’s rights, from 1859, 1869, 1874, and 1919.

“During the entire period of the struggle for women’s enfranchisement, there was widespread publication of cartoons ridiculing the cause. The comic legend was one of the most effective weapons employed to combat the women’s rights movement. Suffragists who bravely withstood taunts and insults were occasionally defeated by scornful laughter.”

– Mary Stetson Clarke

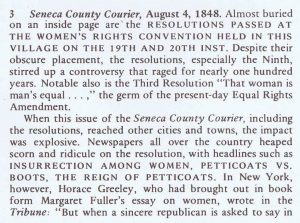

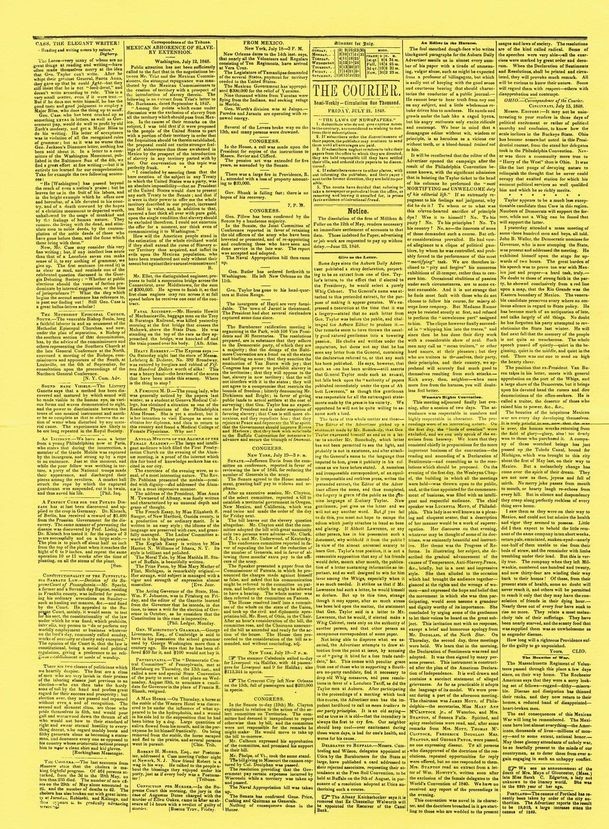

The following excerpts from the 1974 issue of The Jackdaw, take us to Seneca Falls, NY, for the Women’s Rights Convention of 1848. Arnold N. Barben comments on the pages from the Seneca Falls Courier.

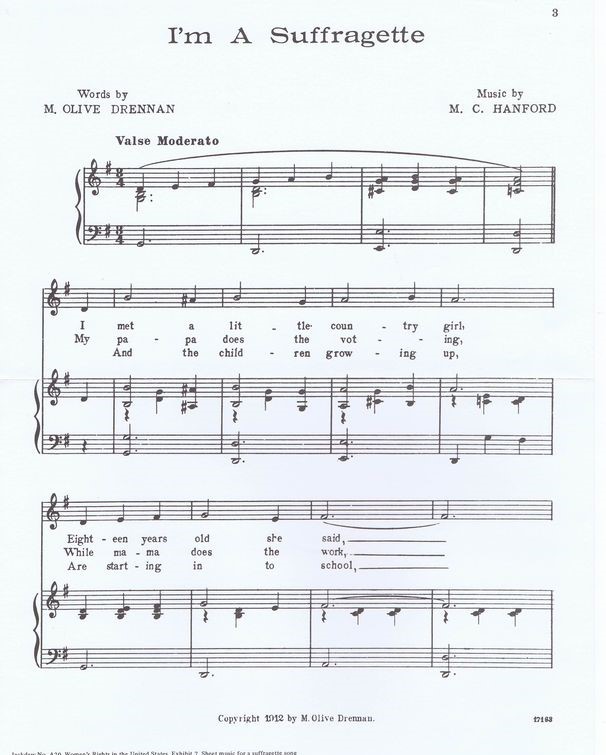

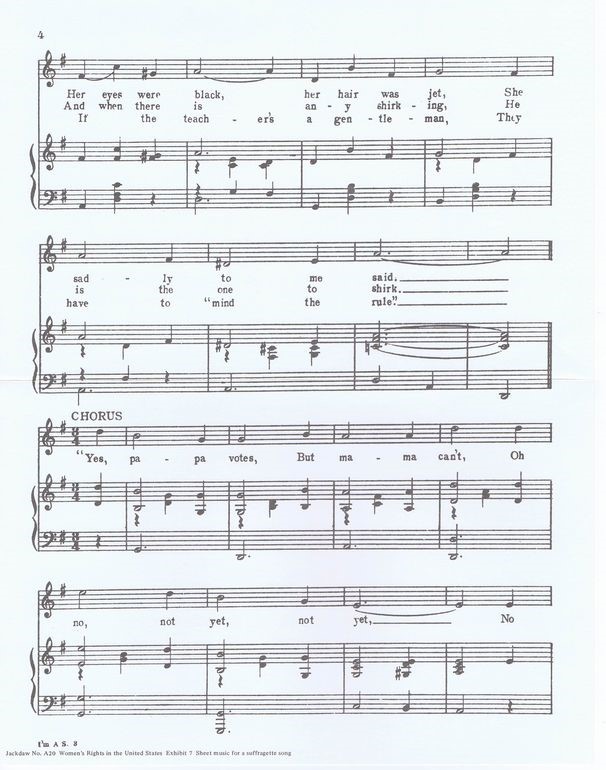

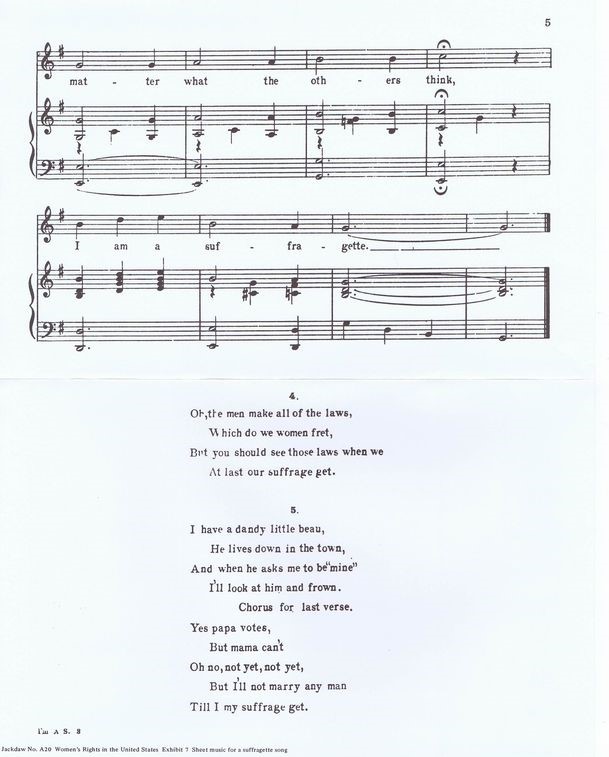

From The Jackdaw includes sheet music for “I am a Suffragette” (1912) music by M. C. Hanford and lyrics by M. Olive Drennan.

Want to sing along? Here’s a video of Jane Voss singing this song, accompanied by Hoyle Osborne on piano: I am a Suffragette video

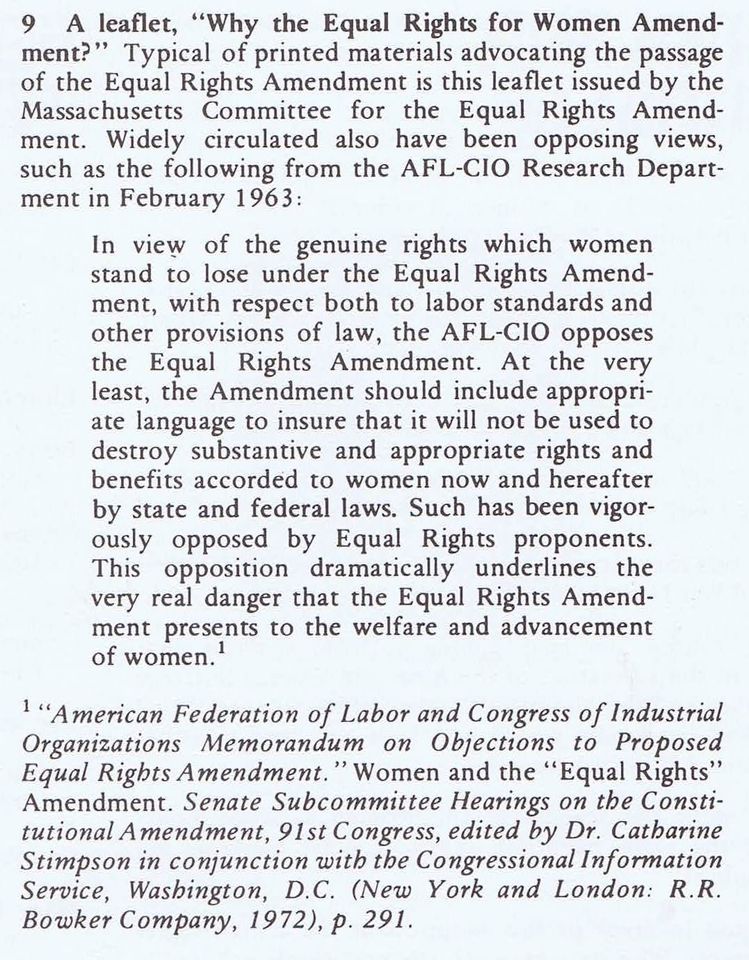

With 1974 fast retreating in the rear-view mirror of history, the contemporary exhibits that Mary Stetson Clarke included in The Jackdaw are now of historical interest to the young and nostalgic interest to those who lived through that era of second wave feminism in the United States.

Here we have a leaflet supporting the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

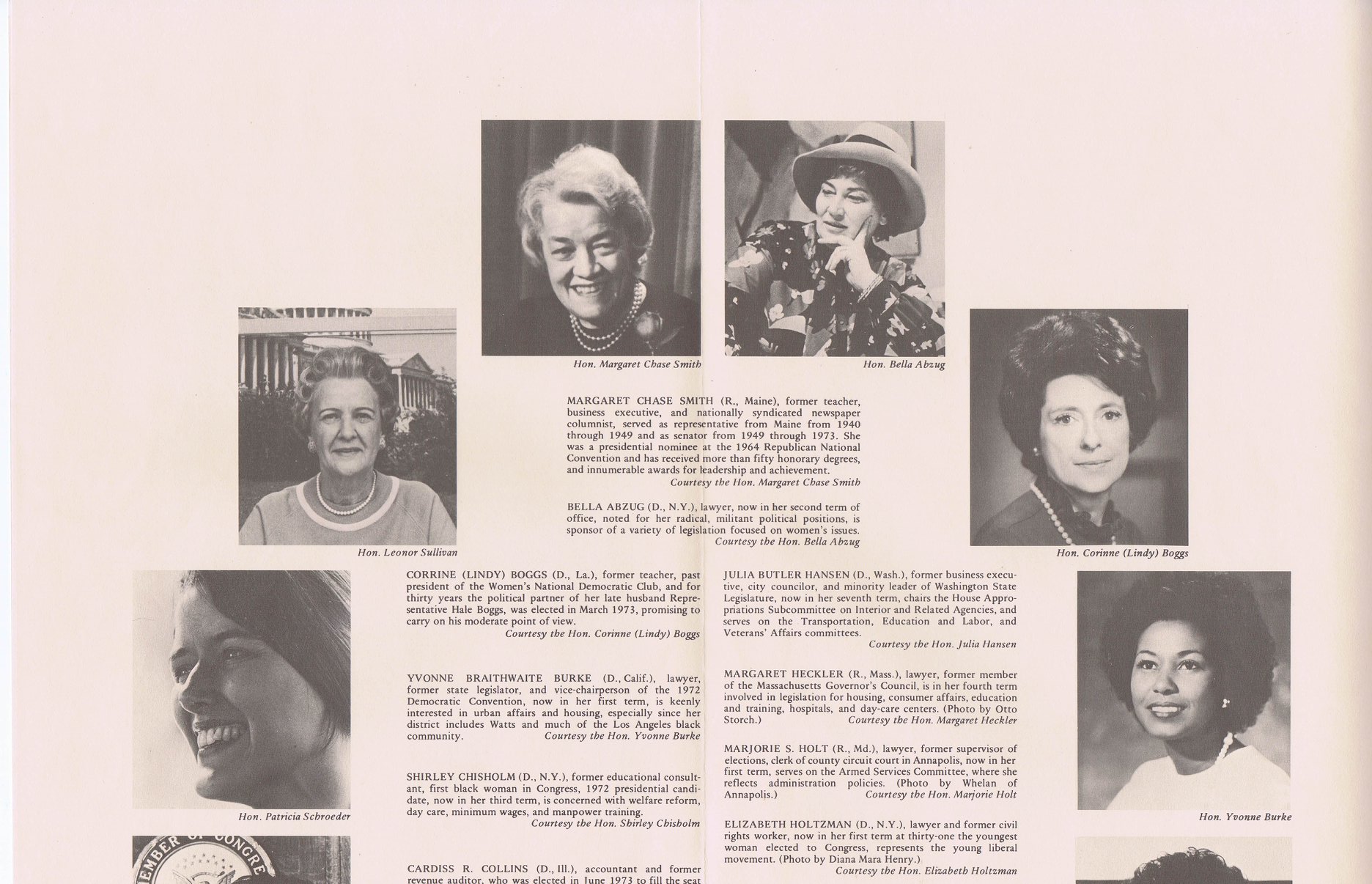

Here Clarke provides a collage of women who have served in Congress up to 1974. We apologize that some of the images and text were not scanned fully.

How many more could we add to that list today?

Do you have women in your family whose stories should be told and preserved at the Williamstown Historical Museum. We would like to collect and share the stories of all of Williamstown’s residents. Email Sarah at [email protected] to tell us your story. To learn more about our Summer of Suffrage, click here: Summer of Woman Suffrage Online Exhibit

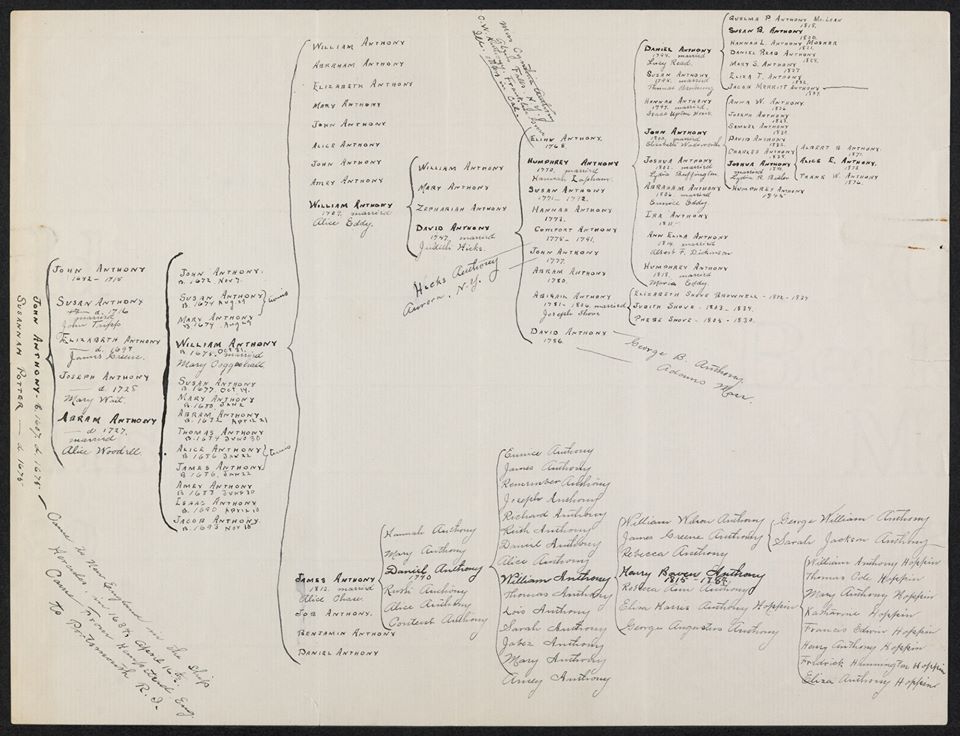

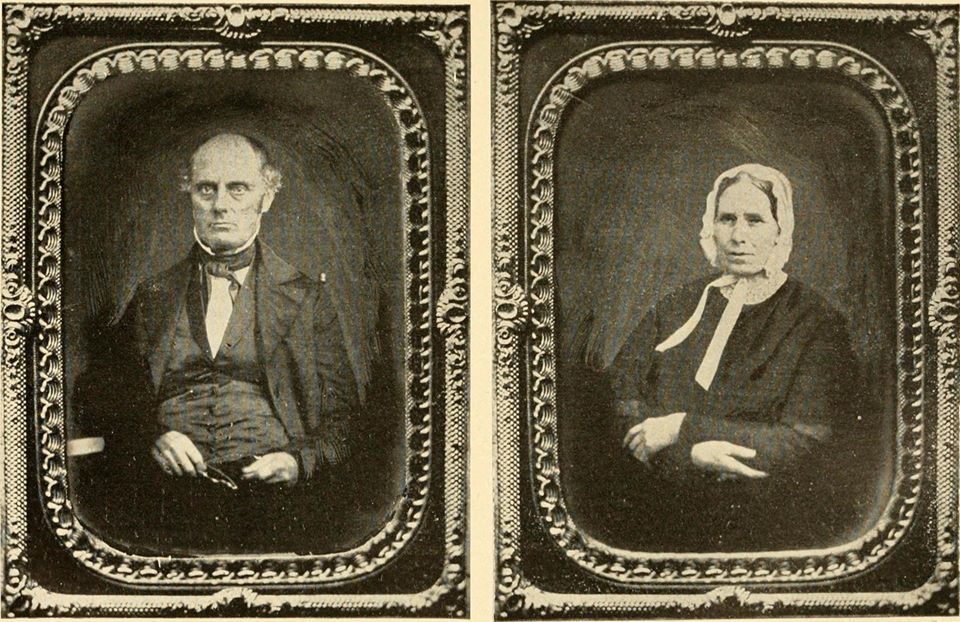

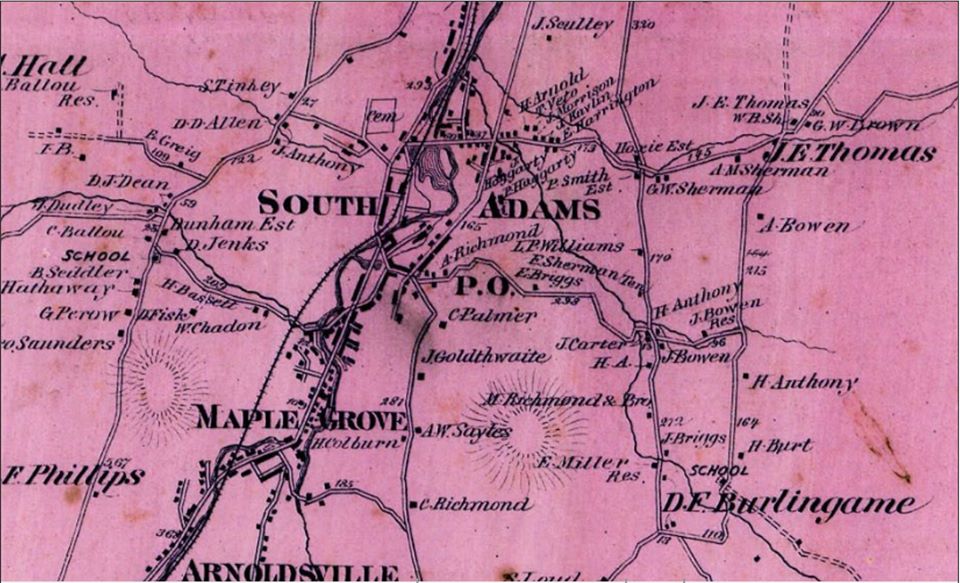

Daniel and Lucy Anthony

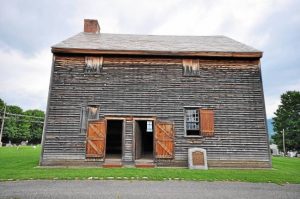

Daniel and Lucy Anthony Quaker Meetinghouse in Adams

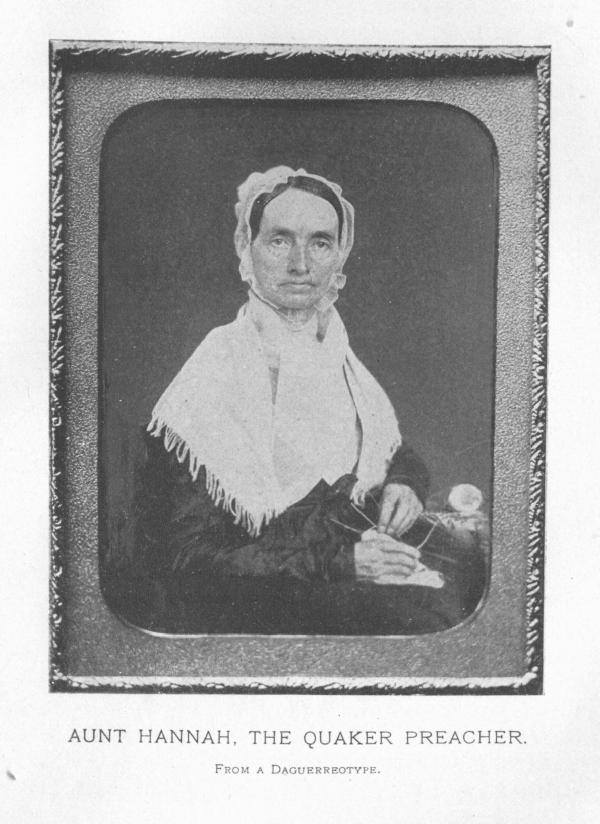

Quaker Meetinghouse in Adams Hannah Anthony Hoxie, Daniel Anthony’s sister

Hannah Anthony Hoxie, Daniel Anthony’s sister

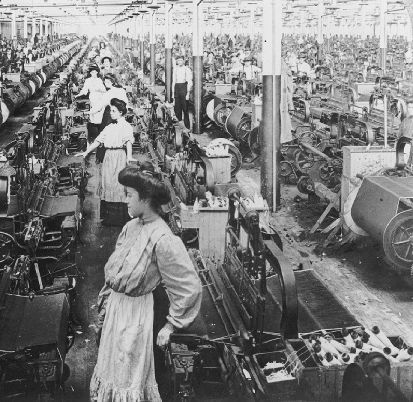

Quaker Meetinghouse interior

Quaker Meetinghouse interior