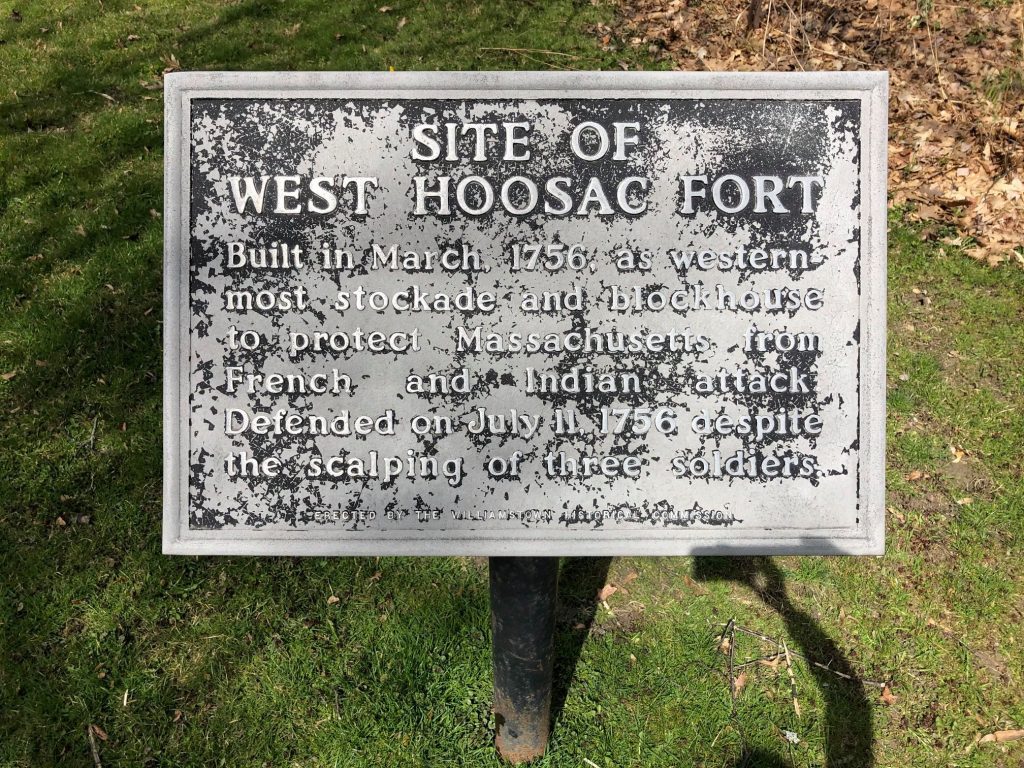

Our final marker commemorates the location of a structure vital to the founding of our town: West Hoosac Fort.

In late May of 1754, a year after the first proprietors’ meeting in West Hoosac (Williamstown), native Americans attacked what is now Hoosick and Hoosick Falls, NY, about 12 miles downstream on the Hoosic River.

Arthur Latham Perry notes in Origins in Williamstown, 1894, “All the settlers at West Hoosuck immediately abandoned the place on news of possible approaching attack ravages below them; those who had families betook themselves to Fort Massachusetts, where they were not very welcome, and others returned to their homes over the mountain or into Connecticut.

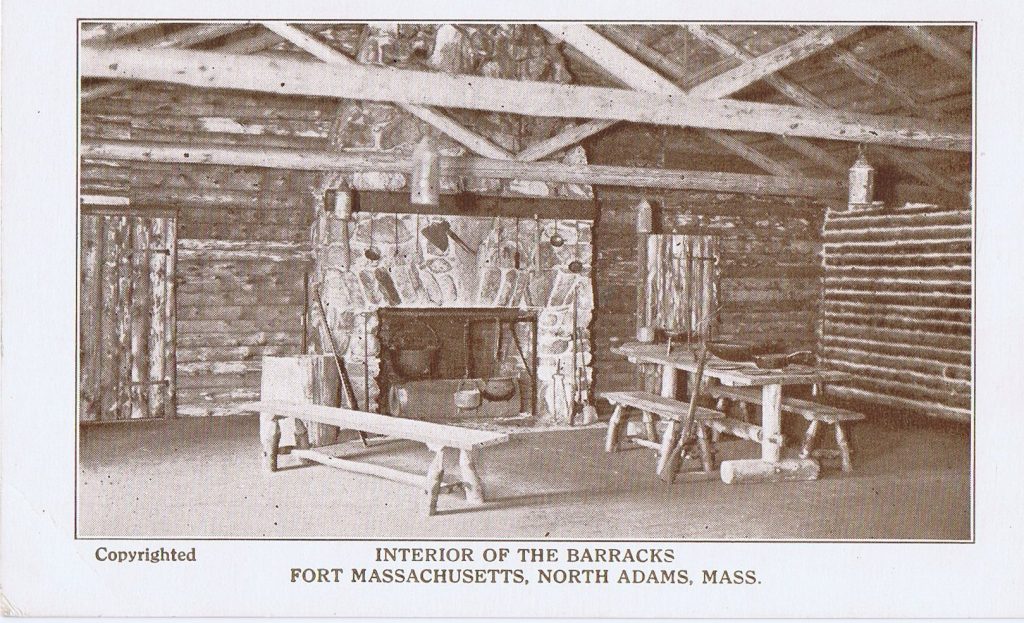

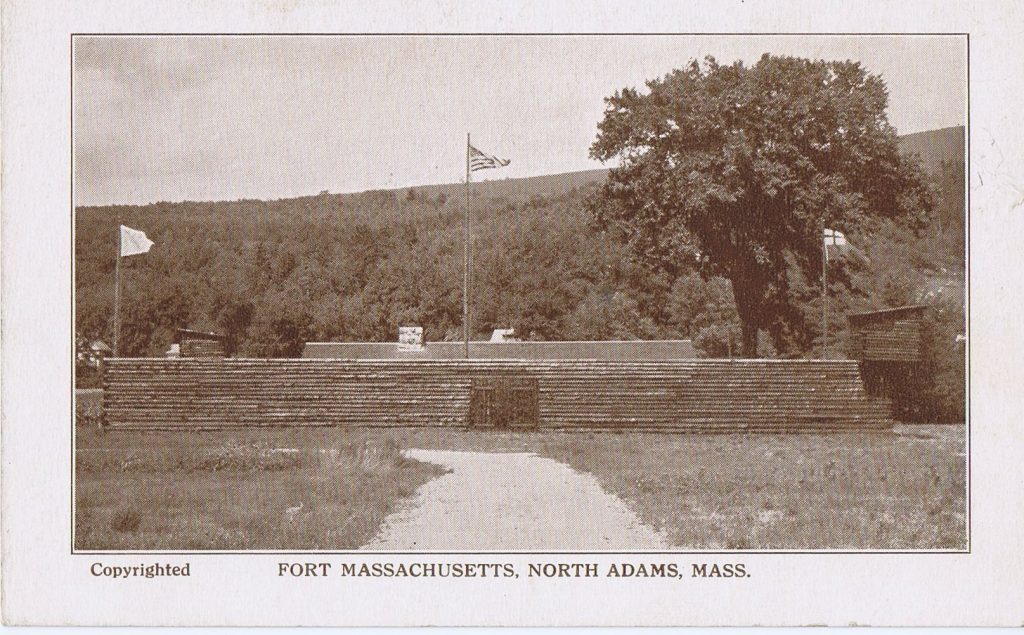

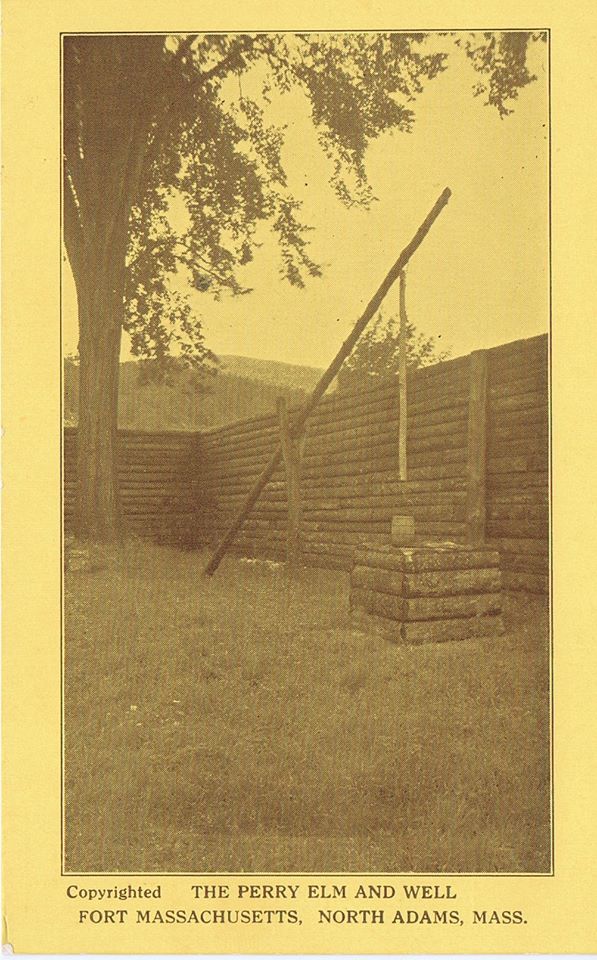

Images of the 1930s reproduction of the Fort Massachusetts

This bold incursion taught two important lessons. It taught the people of Connecticut that they were much exposed to Canada by way of the Housatonic, and that they ought to help the “Bay” to defend the gateway of the Upper Hoosac…the other lesson taught…was, that Fort Massachusetts was not well placed to defend the frontier towns in what is now Berkshire from the French and Indians. It stood to one side of the hostile route. This…doubled the confidence of the West Hoosac settlers, who were at the same time soldiers, to demand of the General Court a fort of their own, to be manned by themselves.”

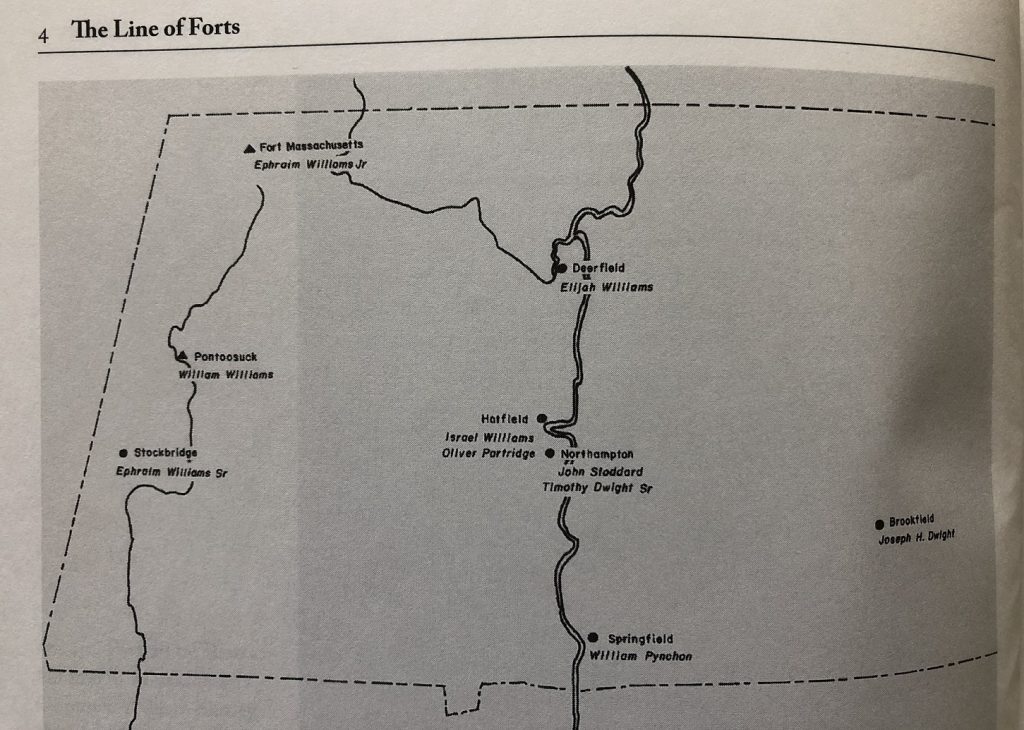

The Line of Forts from present-day Bernardston to Williamstown

Over the next two years several pleas for the establishment of a fort here were sent to Governor Shirley, but it wasn’t until this pathetic appeal in January, 1756, from William Chidester, that action was taken (spelling and capitalization original):

“Your Petitioner and Some others TO THE AMOUNT OF FIVE FAMILYS are left alone in said Westerly Township as he apprehends in Emmenant Danger of being Murthered, and their substance destroyed by the Common Enimy…”

Gov. William Shirley by Thomas Hudson

National Portrait Gallery

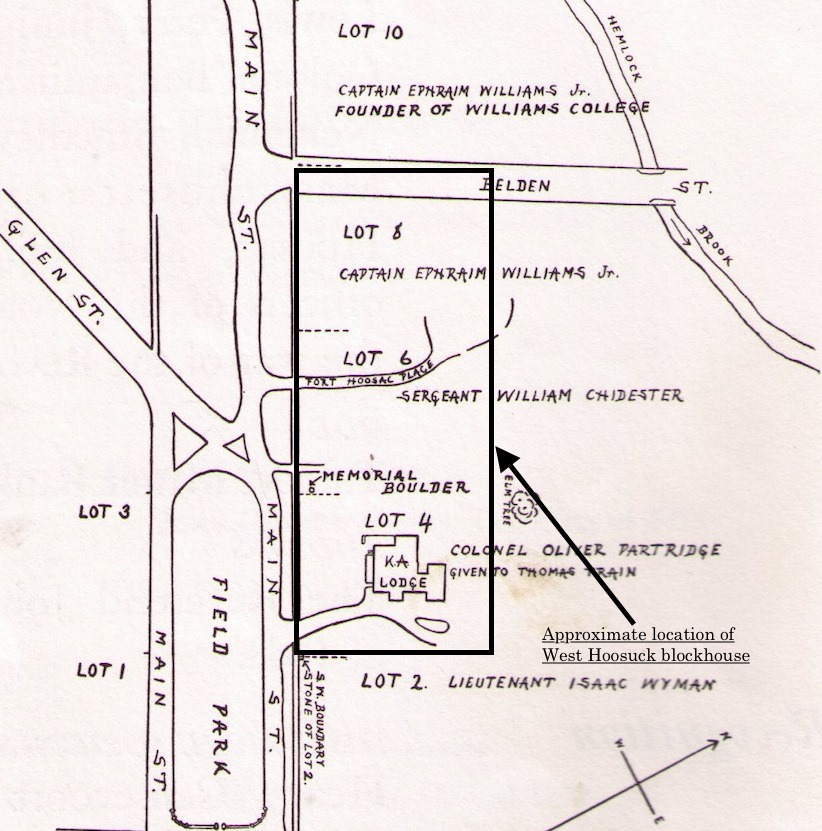

Perry continues to explain: “Governor Shirley issued an executive order on the 6th of February in accordance with Chidester’s request, authorizing him to build a blockhouse on the ‘Square,’ – that is, in the Main Street on the third eminence, — if he could induce a sufficient number of the proprietors to join him so as to complete the work by the 10th of March; otherwise to build the block house on his own lot, house lot No. 6, and afterwards to picket the front part of that lot and of the lot next west, house lot No.8.

Chidester only found encouragement to do the lesser thing. Benjamin Simonds, Seth Hudson, and Jabez Warren, three of the oldest homesteaders..chipped in to aid him in his work. These four men commenced at once to erect the blockhouse on the eastern line of No. 6 where it touched the Main Street and several others who had left on the alarm in 1754, and among them Nehemiah Smedley and Josiah Hosford and William Hosford…returned and aided in the work.

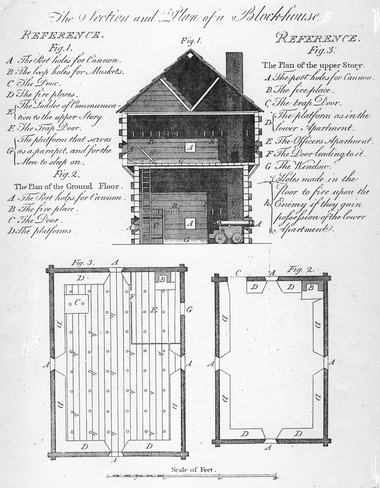

A typical blockhouse

Ten men from Fort Massachusetts served as a guard from February 29th to March 29th, when the block house was finished. We can not tell exactly when it was done, but we know that pickets were set after the manner of Fort Pelham [a block house located in Rowe, MA, and ordered abandoned in 1954] around the fronts of both of those lots, enclosing the two houses…A good well was also within the enclosure. This rude work, not very well placed, and not meeting the views of a considerable number of the resident proprietors, was called ‘West Hoosac Fort,’ and it had a history, as we shall see.”

“It was inevitable, in the nature of things, that jealousy should spring up between the newer and the older forts in one small valley,” writes Arthur Latham Perry, “Origins in Williamstown” 1894

In April of 1756, in obedience to this order, Captain Isaac Wyman detailed five men from Fort Massachusetts, under the command of Sergeant Samuel Taylor, to guard the new fort, in connection with the men who had built it. This put the new fort under the control of a subaltern of the old one. So West Hoosuck resident William Chidester went to Boston in April, and obtained a Sergeant’s commission from Governor Shirley and the authority to supersede Taylor in the command of the new fort.

Perry further notes: “There seems to have been another jealousy stirring in the minds of these men…namely, the antipathy between the Connecticut men and the men of the Bay. Chidester and his chief friends were from the southern colony; most of the other leading men were from the eastward. This colonial bickering had certainly broken out at Lake George the fall before…”

In May of 1756 there were rumors of an enemy approaching from the northwest. The block house had no artillery at all and just ten men as a garrison. In June Chidester again took a petition to Boston urging the General Court not to rebuild Fort Massachusetts – “which is a considerable part of it fell down and it is Daly expected that the rest will fall” – but to fortify West Hoosuck to fulfill the same purpose of protecting the western boundaries of the Colony.

On June 11, as Chidester was returning from Boston without much encouragement for his petition, a series of hostile operations by French and Indians forces began along the Hoosic River, which cost several lives.

The Line of Forts from The Line of Forts: Historical Archealogy on the Colonial Frontier of Massachusetts by Michael D. Coe, 2006

It had long been the custom to keep small scouting parties in motion from fort to fort, from the Connecticut to the Hoosic, and down that river to the Hudson, and then back again, as this was the main source of news. Benjamin King and William Meacham had been sent on such an errand down the Hoosic by Captain Wyman, when, returning, they fell into an ambuscade only about three-quarters of a mile from West Hoosuck Fort and both were killed.

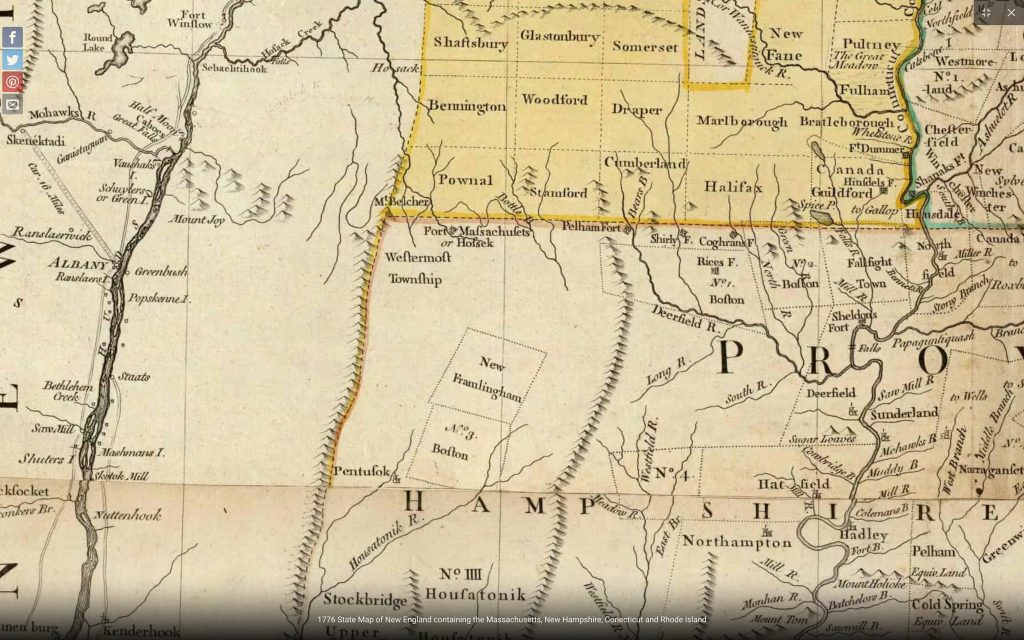

A close up from the 1776 map of our region in Jeffrey’s The American Atlas: Or, A Geographical Description Of The Whole Continent Of America

The tribes or communities of Indigenous People in this region were referred to as the Schaghticoke and were a part of the Mohican nation.

Fifteen days after Benjamin King and William Meacham were been killed by natives in June 1756 , a detachment of thirteen soldiers from the encampment at Half Moon were on their way to Fort Massachusetts when they were surprised in the town of Hoosac (now called Hoosick Falls or Hoosick, NY) about thirteen miles downstream of the fort, Eight of them were killed and the remaining five captured.

The next day, a small party was sent from Fort Massachusetts by Captain Wyman to reconnoiter the ground and possibly bury the dead, but upon approaching the place they found a large group of Schaghiticoke people, and Wyman and his group retreated. General Winslow detached a corps from Half Moon, who took possession of the ground and buried the slain.

Arthur Latham Perry notes in Origins in Williamstown, “On July 11, 1756, as William Chidester and his son James and Captain Elisha Chapin were looking for some strayed cows along Hemlock Brook at some little distance from their fort on the hillside above the brook, an Indian volley killed the two Chidesters, and wounded Chapin, who was seized, carried off about sixty rods, and killed and scalped.

The Indians then pressed up the hill, opened fire upon the block house, killed the cattle in the vicinity, and soon after retreated into the woods. Nobody dared, apparently, to carry the news at once to the other fort; and it was only on the second day from the attack that Captain Wyman sent twenty men to search for the body of Captain Chapin, who found him and buried him in a decent manner and returned with his family to Fort Massachusetts.”

Seth Hudson succeeded to the command of the West Hoosac Fort upon William Chidester’s death in July 1756. More men were billeted at West Hoosuck, and ammunition and food were supplied from Fort Massachusetts, but the majority of settlers were unhappy with what they perceived as inadequate supplies of men and provisions. There continued to be a schism between settlers from Connecticut, and those from eastern Massachusetts, with the former in favor of building up West Hoosuck and the latter wanting to refortify Fort Massachusetts.

In January of 1757, twenty-one West Hoosuck settlers petitioned Boston to redress of their grievances, and in typical governmental fashion, a committee was formed and no action was taken.

Hudson petitioned again in April of that year with the result that Timothy Woodbridge, Esq., a frontiersman from Stockbridge was ordered to “repair to the western frontier, and examined fully into the state of affairs there.”

Woodbridge made a thorough examination of the lay of the land and listened to complaints and concerns from both sides and within a month presented a full report to the General Court in Boston that was much more favorable to the West Hoosuck settlers and their claims than anything before.

Woodbridge believed that Fort Massachusetts was only built where it was because no one knew any better at the time, and that “…the enemies chief gangway to the western frontiers is about the west part of the west Township.” They found Fort Massachusetts “much decayed but still in such condition as may answer for a while” without the expense of repair, while the block house at West Hoosuck was deemed “…a place of considerable strength and tolerable situation…” which being fortified and additionally manned could be “…maintained against a considerable force.” He further stated that almost all of the settlers complaints were valid and that adding an additional twenty men to the ten already billeted to West Hoosuck would be a “public service.”

Another part of the Woodbridge committee’s report related to the conduct of Captain Isaac Wyman in his capacity as commander at Fort Massachusetts, to Major Elijah Williams as commissary at the west, and to Colonel Israel Williams as commander of the entire western region. According to Arthur Latham Perry: “A large mass of testimony was taken, including numerous depositions, in behalf of, and in opposition to, the complaints of the petitioners, which papers, in confusing abundance, are now in the secretary’s office at Boston.”

Portrait of British General Jeffery Amherst by Joshua Reynolds.

Portrait of British General Jeffery Amherst by Joshua Reynolds.

The name of Lord Jeffery Amherst is not often mentioned in polite conversation in Williamstown these days, both from the historic rivalry between the colleges and Lord Amherst’s relentless attacks on indigenous communities during his lifetime, but in western Massachusetts in the 1750s-1760s he was a major contributor to the end of the French and Indian War, whose military victories had a direct impact on life in the upper Hoosic Valley.

Perry states, in his 1894 Origins in Williamstown, “From the moment that the military temper and resources of General Jeffery Amherst were understood in New England, let us say from Sept. 30, 1758, the individual importance of the two forts on the [Hoosic River] began steadily to decline, and of course also the bitterness and bickerings between them.

It is pleasant to note, that the last official request of the commander of the West Hoosuck Fort was, that his garrison and neighbors might share in the privilege of hearing the preaching of the chaplain at the older fort a part of the time.”

There had been no proprietors’ meeting called or held here for six years and six months, when Captain Isaac Wyman, still nominally the proprietors’ clerk, was requested to call one in September of 1760. Notably, he dated this meeting call “East Hoosuck,” not “Fort Massachusetts.”

Wyman had not relished the charges so persistently made against him as commander of Fort Massachusetts by his co-proprietors in West Hoosuck and he lost interest in the governance of this town. At that 1760 meeting William Horsford was chosen clerk in his place; and in November 1761 the Registry of Deeds records that “Isaac Wyman, Gentleman of Fort Massachusetts, sold to Benj. Kellogg of Canaan, Connecticut, for £140 all his lands in West Hoosuck, including his fine house lot No. 2, “

Wyman left western Massachusetts and moved to Keene, New Hampshire, where his tavern still stands today as an historic museum. Wyman Tavern was built in 1762 and is Keene’s most historic house.

Photo of Isaac Wyman’s Tavern in Keene, New Hampshire, taken before 1905

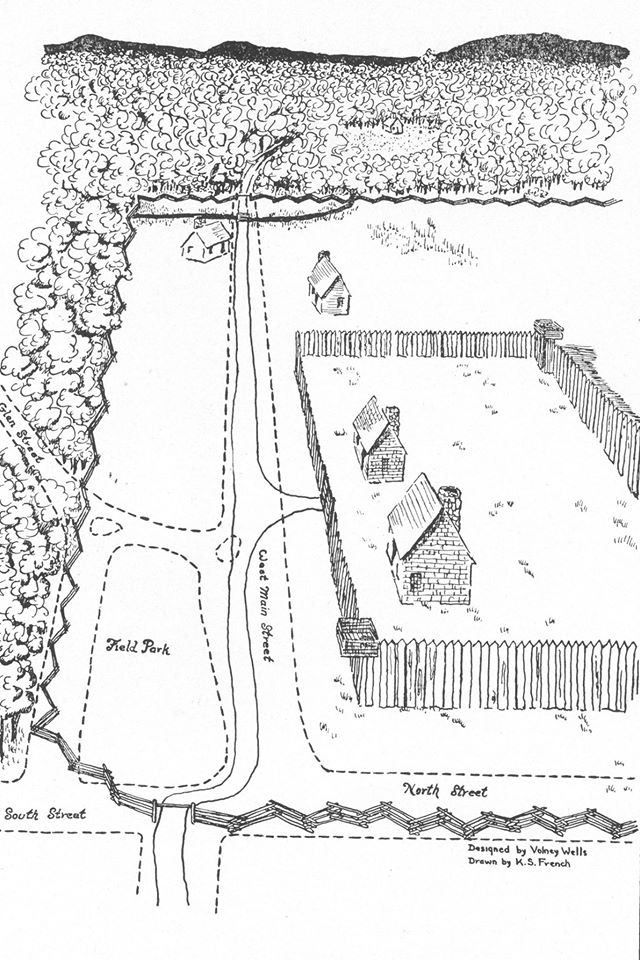

So where was West Hoosuck Fort? The following maps show it on the property along Field Park where the Williams Inn stood from 1974-2019. You’ll find this week’s historical marker and a boulder with a commemorative plaque at the west end of that lot.

In Origins in Williamstown (1894), Arthur Latham Perry writes about the demise of the West Hoosuck Fort and how, in the late 19th century, he could establish exactly where the block house stood,

“The decadence and final disappearance of West Hoosuck Fort was similar in its course to that of [Fort Massachusetts]. Besides the block house, there were two other houses within the pickets, all standing on the front of lots 6 and 8, the block house being on the eastern line of the third house lot (6) west of North Street, and the two other houses still further west, on the declivity towards Hemlock Brook. The picket line was 28 rods long on Main Street.how far the picket lines extended northward and consequently how much land was enclosed by them; there are no present means of determining; but the position of the blockhouse and the easterly line of pickets can be determined almost exactly….”

(Perry continues in great detail with the measurements!)

After the battles of the French and Indian War moved elsewhere and military protection became less necessary, at least four proprietors’ meetings were held within its rude walls of hewn timber until the Fort was abandoned in 1761.